Overthrow or wilful act of fielder - Laws of Cricket

|

Cricket Anatomy™

Law 18.12.2 (Batsman returning to wicket he/she has left) shall apply as from the instant of the throw or act.

view template

|

Yesterday’s enrapturing Cricket World Cup final threw up a key decision, when, three balls from the end of the match, Martin Guptill’s throw from deep-midwicket, which was going to be a direct hit and run Ben Stokes out[1], cannoned off the back of Stokes’ flailing bat as he dived desperately in the distant direction of the crease and ran down and over the boundary for overthrows. But how many overthrows? It was to prove crucial.

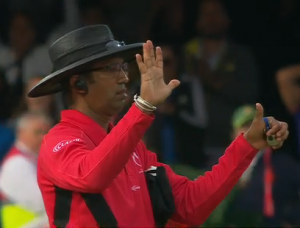

With haste which might transpire to be unseemly, Umpire Dharmasena held six fingers up to the scorers: four representing runs for the boundary overthrow; two for the runs the outfield batsmen completed.

Yet, a quick look at Law 19.8 tells a different story: where the boundary results from “an overthrow or from the wilful act of a fielder”, the runs scored shall be (a) any applicable penalties (wides or no-balls: here, none); (b) the allowance for the boundary (four); (c) completed runs (one); together with the run in progress if they had already crossed at the instant of the throw or act.

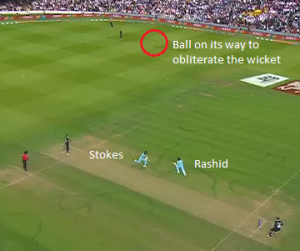

The wilful act in question is Martin Guptill’s throw from deep midwicket, whence Ben Stokes had flukily shanked the ball. The ball’s subsequent deflection by Stokes’ bat from what was obviously its true path to obliterate the wicket leaving the England hero tragically, but undoubtedly, short of his ground is not a “throw”, much less a “wilful act of a fielder” — it has no cricketing significance at all, in fact — so is irrelevant to the question of whether the batsmen had crossed. The only question is where were they were in relation to each other at the time Guptill let fly his spear of burning gold on its true path towards Stokes’ wicket.

And at that point, Ben Stokes and Adil Rashid had not passed each other (“crossed”), as this picture demonstrates.

Now there is a kicker, because, having only scored one conventional run, the batsmen should have returned to where they started that run, leaving Rashid to face the next ball, with Stokes at the non-striker’s end: “Law 18.12.2 If, while a run is in progress, the ball becomes dead for any reason other than the dismissal of a batsman, the batsmen shall return to the wickets they had left, but only if they had not already crossed in running when the ball became dead.” (Note that the “moment the ball became dead” was, under rule 19.8, “the instant of the throw or act.”

So Adil Rashid should have been required to face the final two balls, and obliged to score four, not three, runs to win.

And here is where the path dependency of Cricket illustrates why we can’t undo history: We can say with some confidence that Stokes would only score three off those final two balls, because that is what he did do. But we don’t know what Adil Rashid would have done: he was denied the chance to smear the ball over cow corner for six match-winning runs as no doubt he will say he would have done.

And this is why cricket is such a good metaphor for life. There may be caprice, cruel fate, uncertainty and clamity, but the overall experience is all the more magnificent for it.

The record remains as it was written: well played England; worthy World Champions.

See also

References

- ↑ Prove it wouldn’t have okay?