You can lead a horse to water

|

Office anthropology™

|

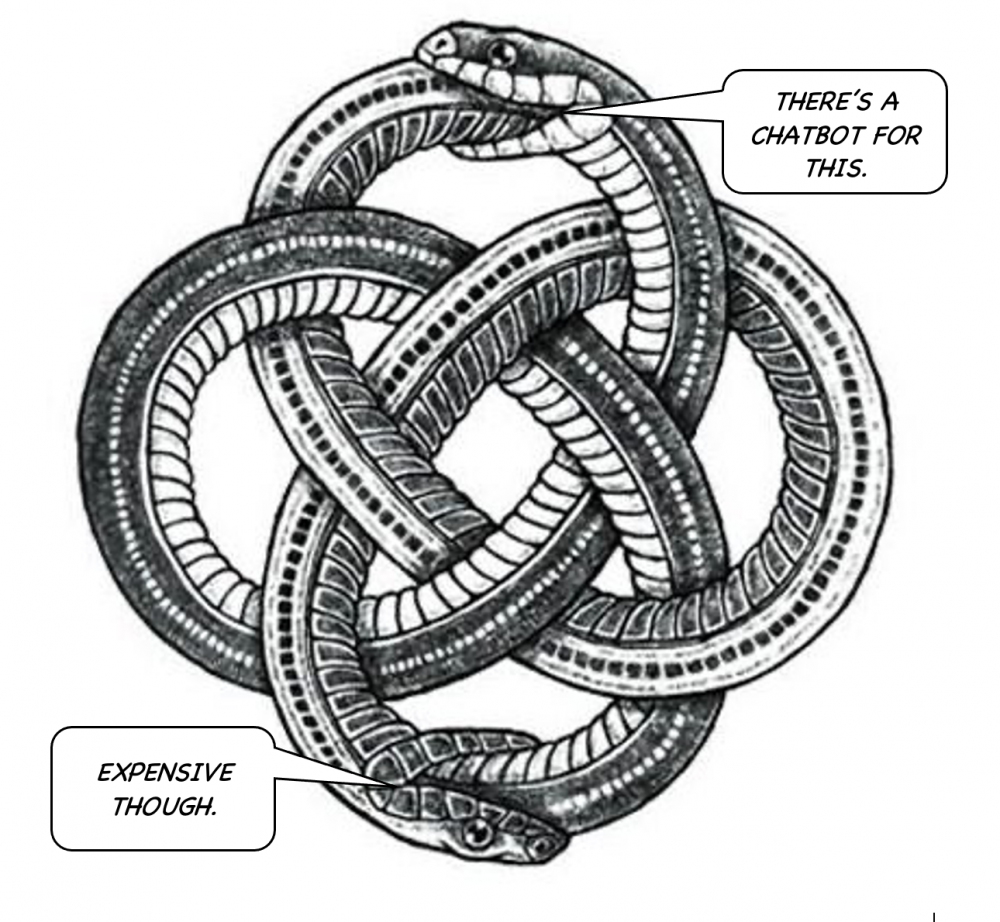

It is one thing designing an order-of-magnitude-better, revolutionary app; quite another to get it through the Hunger Games experience that is procurement and information security clearance — budget 18 months in spent time and five to ten years off your life — but all that pales into infinitesimal irrelevance compared with the task, once installed on the desktops, of getting any lawyers to use it.

This presents a further hurdle to legaltech implementation, seldom spoken of but every bit as gruesome. For if take-up is not immediate and universal, in an obscenely short period of time, some officious twerp from the operating office will be along with a clipboard asking why no-one is using it, whether it is really value for money, and threatening to off-board it before quarter end. This is the dilemma: before you buy it, legaltech is the promise of innovation, performative thought-leadership and digital prophecy. After you’ve bought it, legaltech is an operating cost. An operating officer is attracted like a moth to both, so they turn out to be symbiotic.

Here is the thing: the legaltech promise is to boost productivity. In private practice, enhanced productivity is, at least in theory, correlated with increased, hard-dollar, revenue.

But inhouse, it is assuredly not. Inhouse counsel don’t generate revenue; they are not allowed to. They cost revenue. This is not just by coincidence: the legal department is by its very ontology a cost centre.[1]

Yet the legal ops team remains fixated on legaltech. This is not just because its personnel are easily led, but also because they have been told: “GET OUT THERE AND INNOVATE SO HELP ME”. This is, needless to say, management code for, “you must use legaltech to shave 15% off the legal budget and at the same time make us look like digital wizards.”

As ever, the single, unrelenting focus — notwithstanding four good decades of academic unanimity that it is the wrong thing to focus on — is reducing cost.

That, in turn, is predicated on the belief — widely shared by thought leaders and wishful academics, however absurd — that legaltech is a cheap way of replacing lawyers. This is the general counsel’s desperate hail-Mary: some snappy legaltech will demonstrably, and quickly, save hard dollars.

But giving productivity-boosting tools to inhouse lawyers does not save hard dollars. To the contrary, it costs hard dollars. Lots of hard dollars. As soon as this dawns on the legal ops team it will stampede to remove it again.

Our metaphor of the bucket painters refers.

The polishing team say, “we take the bucket, polish it, and give it to the priming team.”

The priming team say, “we take the polished bucket, prime it, and give it to the painting team.”

The painting team say, “We take the primed bucket, paint it, and give it to the drying team.”

The drying team say, “we take the painted bucket, dry it, and give it to the stripping team.”

The stripping team say, “we take the dry bucket, strip it, and give it to the polishing team.”

Unless it is a management-sanctioned monitoring or measuring tool, like time recording of document management (in which case no-one will use it, but the middle management ouija board will bloody-mindedly persist with it in the face of utter failure) — that is, if it really boosts productivity: a formatting fixer, a deltaview application or something of that nature — the moment the first invoice arrives management will implement a use-monitoring project with the express goal of concluding no-one needs it, so it can be junked in a cost saving drive.

Now: could someone pass me a bucket?

To paint, obviously.

See also

References

- ↑ As the JC is fond of saying, the last time a big firm tried to turn one of its control functions into a profit centre, it didn’t work out so well.