Telegraph Road: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

As a young fellow growing up in the 1980s, the rock band Dire Straits was about as uncool as could possibly be. Not only because it was a colossal global dinosaur (“''so'' commercial”, we [[sneered]], and went back to our bootlegged tapes of Joy Division gigs in Belgium),<ref>[https://www.joydiv.org/G3.htm Gruftgesaegne], as I recall.</ref> but because its music was so unapologetically ''middle of the road''; its band-members so ''square''. | As a young fellow growing up in the 1980s, the rock band Dire Straits was about as uncool as could possibly be. Not only because it was a colossal global dinosaur (“''so'' commercial”, we [[sneered]], and went back to our bootlegged tapes of Joy Division gigs in Belgium),<ref>[https://www.joydiv.org/G3.htm Gruftgesaegne], as I recall.</ref> but because its music was so unapologetically ''middle of the road''; its band-members so ''square''. | ||

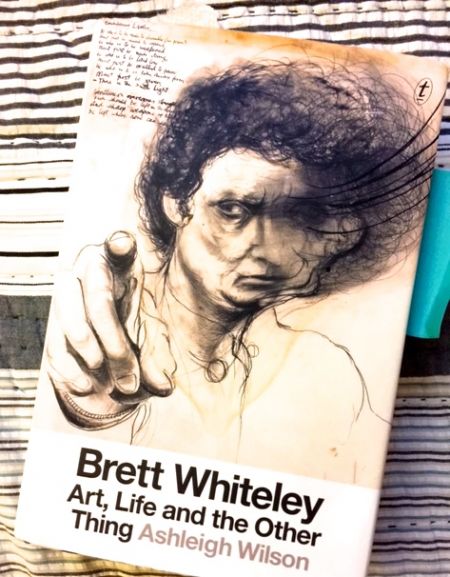

You mellow as you get older. It took me until my twnties: sometime, I think, in the 1990s. In this case enlightenment came by way of epiphany: watching a documentary about the Australian painter Brett Whiteley . In it, Whiteley was filmed at work in his studio, an enormous canvas on the floor, Jackson Pollock style (I recall it was of sea-birds, but I may well be confusing that with something else). Before he started work, he cued up Dire Straits’ 1982 epic ''Telegraph Road'' on his turntable, and turned it up very loud. ''Seeing'' the song in this way — seeing how, a troubled, gifted artist like Whiteley heard it, put it in a very different context.<ref>I’ve not been able to find the documentary online — if anyone recognises it, let me know. Whiteley died of a heroin overdose in 1992, so it may well have been some retrospective documentary of his work published around that time.</ref> | You mellow as you get older. It took me until my twnties: sometime, I think, in the 1990s. In this case enlightenment came by way of epiphany: watching a documentary about the Australian painter [[Brett Whiteley]]. In it, Whiteley was filmed at work in his studio, an enormous canvas on the floor, Jackson Pollock style (I recall it was of sea-birds, but I may well be confusing that with something else). Before he started work, he cued up Dire Straits’ 1982 epic ''Telegraph Road'' on his turntable, and turned it up very loud. ''Seeing'' the song in this way — seeing how, a troubled, gifted artist like Whiteley heard it, put it in a very different context.<ref>I’ve not been able to find the documentary online — if anyone recognises it, let me know. Whiteley died of a heroin overdose in 1992, so it may well have been some retrospective documentary of his work published around that time.</ref> | ||

I’ve seen the song, and the band, in a completely different way ever since. Their music is not perfect — Knopfler aspired to grandiosity when he might have avoided it, and most of his songs after '' | I’ve seen the song, and the band, in a completely different way ever since. Their music is not perfect — Knopfler aspired to grandiosity when he might have avoided it, and most of his songs after ''Communiqué'' are too elaborate and too long, but if you can see through that there is real fibre and real muscle behind. | ||

So, short advice: to get the most out of ''Telegraph Road'', put yourself in a place of maximum potential exhilaration — up a high mountain, or driving fast through the desert ([[Otto Büchstein|our]] favourite locales include the Desert Road in New Zealand’s central plateau, or the McKenzie Country, in her southern wilds, and the Mojave desert between L.A. and Vegas). | So, short advice: to get the most out of ''Telegraph Road'', put yourself in a place of maximum potential exhilaration — up a high mountain, or driving fast through the desert ([[Otto Büchstein|our]] favourite locales include the Desert Road in New Zealand’s central plateau, or the McKenzie Country, in her southern wilds, and the Mojave desert between L.A. and Vegas). | ||

Revision as of 09:35, 21 February 2021

|

Jolly Contrarianism & Devilish Advocacy

|

One of the many consolations about running your own not-for-profit[1] wiki is you can decide what the hell to put on it. The JC loves guitars as you all know, and does like a good rock song.

Radio with pictures

As a young fellow growing up in the 1980s, the rock band Dire Straits was about as uncool as could possibly be. Not only because it was a colossal global dinosaur (“so commercial”, we sneered, and went back to our bootlegged tapes of Joy Division gigs in Belgium),[2] but because its music was so unapologetically middle of the road; its band-members so square.

You mellow as you get older. It took me until my twnties: sometime, I think, in the 1990s. In this case enlightenment came by way of epiphany: watching a documentary about the Australian painter Brett Whiteley. In it, Whiteley was filmed at work in his studio, an enormous canvas on the floor, Jackson Pollock style (I recall it was of sea-birds, but I may well be confusing that with something else). Before he started work, he cued up Dire Straits’ 1982 epic Telegraph Road on his turntable, and turned it up very loud. Seeing the song in this way — seeing how, a troubled, gifted artist like Whiteley heard it, put it in a very different context.[3]

I’ve seen the song, and the band, in a completely different way ever since. Their music is not perfect — Knopfler aspired to grandiosity when he might have avoided it, and most of his songs after Communiqué are too elaborate and too long, but if you can see through that there is real fibre and real muscle behind.

So, short advice: to get the most out of Telegraph Road, put yourself in a place of maximum potential exhilaration — up a high mountain, or driving fast through the desert (our favourite locales include the Desert Road in New Zealand’s central plateau, or the McKenzie Country, in her southern wilds, and the Mojave desert between L.A. and Vegas).

Mark Knopfler is, of course, a virtuoso. What you learn from this is how less is more: his Fender amps, just gently clipping and the punctuating offbeats and syncopated stabs of his Stratocaster have more throat and more menace than a battalion of wildly saturated rectified amps that were in vogue with the metal bands of the day.

See also

References

- ↑ I should say this is not necessarily by choice, and this may in some parts be due to my desire to put whatever the hell I want on it.

- ↑ Gruftgesaegne, as I recall.

- ↑ I’ve not been able to find the documentary online — if anyone recognises it, let me know. Whiteley died of a heroin overdose in 1992, so it may well have been some retrospective documentary of his work published around that time.