Purpose: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Ok that is a long and fiddly [[metaphor]]. Let us now — sigh — tear ourselves away from Leo Fender’s wonderful creation, and apply the metaphor to the process of preparing, executing and performing a commercial contract. | Ok that is a long and fiddly [[metaphor]]. Let us now — sigh — tear ourselves away from Leo Fender’s wonderful creation, and apply the metaphor to the process of preparing, executing and performing a commercial contract. | ||

Who are the interested constituencies when it comes to the production and use of contracts? It is not just Party A and Party B: it isn’t ''even'' Party A and Party B, if we take the JC]]’s cynical line that each is merely a husk: a host — a static entry in a commercial register somewhere — unless and until animated its ''[[agent]]s''. | Who are the interested constituencies when it comes to the production and use of contracts? It is not just Party A and Party B: it isn’t ''even'' Party A and Party B, if we take the [[Jolly Contrarian|JC]]’s [[Agency problem|cynical line]] that each is merely a husk: a host — a static entry in a commercial register somewhere — unless and until animated its ''[[agent]]s''. | ||

The constituents who have an interest in a contract being done are those in Sales, Legal, Credit, Docs, Operations, Risk, and Trading — on each side of the table — and their external advisors. We see their interests: what they want out of the contract itself, are wildly different: | The constituents who have an interest in a contract being done are those in Sales, Legal, Credit, Docs, Operations, Risk, and Trading — on each side of the table — and their external advisors. We see their interests: what they want out of the contract itself, are wildly different: | ||

*'''[[Sales]]''': To Sales, a contract should be a tool for ''[[persuasion]]'': it should induce the customer to think happy thoughts about her principal — okay, fat chance with a legal contract, but a gal can dream — but at the very least it should be no less intimidating a document than is being presented by her competitors to the same client. Sales will be specially tuned to the message that [[all our other counterparties have agreed this]] should legal or credit baulk at a client request, and will hammer this imperative home, as often as not prevailing. | *'''[[Sales]]''': To [[Sales]], a contract should be a tool for ''[[persuasion]]'': it should induce the customer to think happy thoughts about her principal — okay, fat chance with a legal contract, but a gal can dream — but at the very least it should be no less intimidating a document than is being presented by her competitors to the same client. Sales will be specially tuned to the message that [[all our other counterparties have agreed this]] should legal or credit baulk at a client request, and will hammer this imperative home, as often as not prevailing. | ||

*'''[[ | *'''[[Credit]]''': To credit a contract is a defensive play and the name of the game is, to encode as many snares, booby-traps, tripwires and hundred-ton weights into the document as will be needed in a time of apocalypse. It will not matter that 75% of those contingencies should not, in the life of our universe, come about,<ref>For the obstreperous universe has a habit of playing tricks with people who are meant to know better. This is known as [[Goldman|David Viniar]]’s, or [[Long-Term Capital Management]]’s folly.</ref> nor that Credit would not, in the life of that universe, dream of actually using most the remainder: the exercise is fully hypothetical. For the [[credit]] team’s perspicacity is measured not in ''prospect'', about what in a sensible universe ''might'' happen, but in ''hindsight'' about what, in the mad universe we do inhabit, ''did'' happen. Since at the inception of a relationship this is entirely unpredictable, the beleaguered credit officer has no choice but to select all ordinance available to her, to Sales’ extreme frustration. | ||

*'''[[ | *'''[[Documentation unit|Docs]]''': The documentation team just wants to know who to ask for permission to do what, when. Their line management will be focused only on turnover of their portfolio, how many days delinquent it is. This is a shame, but a consequence of our [[modernist]] obsession with lean production management. It is all very well to set up your assembly line as if it were punting out [[Toyota Corolla]]<nowiki/>s, but your suppliers need to be on message, and generally they are not: the process is captive of fantastical terms imposed by Credit as per the above, rendered in language confected by [[legal]], buffeted by the [[The Structure of Scientific Revolutions|incommensurable]] frame of reference adopted by their counterparty and, more usually, its legal advisors. | ||

*'''[[ | *[[Buy-side legal eagle|'''External legal counsel''']]: The opposing side’s lawyers are mainly interested in showing how clever and useful they are to their client. This they can only do by ''changing the terms of your contract''. This was first articulated in [[Otto Büchstein|Büchstein]]’s articulation of legal existentialism: [[Scribo, ergo sum|''scribo, ergo sum'']].<ref>[[I mark up, therefore I am|I mark-up, therefore I am]]</ref> Now, the more rigorously your baseline contract terms are benched to market, the less scope there is for mark-up: to be sure, one can never entirely rid a document of fussy clarifications and [[For the avoidance of doubt|doubt-avoidance]] parentheticals, but you can minimise them by careful and elegant document design. But this rubs directly against [[Credit officer|Credit]]’s prerogative, above, which is to move the document as far from reality and towards the Platonic ideal of risk management as they can. This no-person’s land is an ideal playground for all the lawyers to mark-up, strike-out, thrust, parry and counter-thrust to their hearts’ consent. If the opposing sides pitch their tents five miles from each other, they cannot know when, whether or on what terms their respective minds will meet. Experience will say there is a fair chance they ''will'' meet, but exactly ''where'' will differ in ever case and, by the time they get there, the location will be shelled, pock-marked and riddled with bullet holes from the negotiation that it will resemble Berlin in 1946. | ||

*'''[[Trading]]''': | *'''[[Trading]]''': | ||

*'''[[Operations]]''': | |||

*'''[[Risk]]''': | *'''[[Risk]]''': | ||

{{Sa}} | |||

* [[Agency problem]] | |||

* [[Design principles]] | |||

{{ref}} | {{ref}} | ||

Revision as of 11:08, 3 November 2021

|

The design of organisations and products

|

For the Purpose of a, NDA, see Purpose - Confi Provision

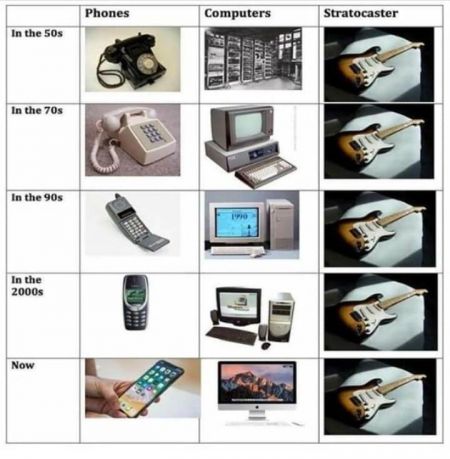

A typically derivative essay on the wonderful Fender Stratocaster got us thinking about how the design imperatives in a process may differ at different points in that process.

An electric guitar’s overall life-cycle includes its design, manufacture, marketing, use, maintenance and further use in perpetuity to kill fascists.[1] The design imperatives for the different phases of its life are very different: during manufacture, what’s important is cost of components, speed and ease of assembly. During sale it is distribution channels, marketing, branding, and transport. Once purchased, the design imperatives are different again: a single careful owner cares not how easy the tremolo is to set up, or the pickguard harness is to wire: she cares about only how easy it is to make, as Frank Zappa put it, “the disgusting stink of a too-loud electric guitar”.

How easy it is to make or sell a guitar bears no necessary relation to how easy it is to play or fix. But note: the interests and aspirations of those who interact with the guitar during its production and use are very different. Leo Fender’s real genius was how fabulously his design managed all these interests, so the same thing delivers for all its users: It’s easy to machine, easy to build, easy to set up, easy to fix, easy to play, it looks great, gets the girls and kills fascists.

Hypothesis, therefore: great design works for all phases, and all users, of an artefact throughout its production and use. Nor is there a strict hierarchy of priorities between these users: you might say “it is more important to be easy to play than to build” — but if difficulty of building doubles its production cost — or makes fixing it more difficult — there will be fewer users. These competing uses exist in some kind of ecosystem in which the artefact will thrive or perish.

Ok that is a long and fiddly metaphor. Let us now — sigh — tear ourselves away from Leo Fender’s wonderful creation, and apply the metaphor to the process of preparing, executing and performing a commercial contract.

Who are the interested constituencies when it comes to the production and use of contracts? It is not just Party A and Party B: it isn’t even Party A and Party B, if we take the JC’s cynical line that each is merely a husk: a host — a static entry in a commercial register somewhere — unless and until animated its agents.

The constituents who have an interest in a contract being done are those in Sales, Legal, Credit, Docs, Operations, Risk, and Trading — on each side of the table — and their external advisors. We see their interests: what they want out of the contract itself, are wildly different:

- Sales: To Sales, a contract should be a tool for persuasion: it should induce the customer to think happy thoughts about her principal — okay, fat chance with a legal contract, but a gal can dream — but at the very least it should be no less intimidating a document than is being presented by her competitors to the same client. Sales will be specially tuned to the message that all our other counterparties have agreed this should legal or credit baulk at a client request, and will hammer this imperative home, as often as not prevailing.

- Credit: To credit a contract is a defensive play and the name of the game is, to encode as many snares, booby-traps, tripwires and hundred-ton weights into the document as will be needed in a time of apocalypse. It will not matter that 75% of those contingencies should not, in the life of our universe, come about,[2] nor that Credit would not, in the life of that universe, dream of actually using most the remainder: the exercise is fully hypothetical. For the credit team’s perspicacity is measured not in prospect, about what in a sensible universe might happen, but in hindsight about what, in the mad universe we do inhabit, did happen. Since at the inception of a relationship this is entirely unpredictable, the beleaguered credit officer has no choice but to select all ordinance available to her, to Sales’ extreme frustration.

- Docs: The documentation team just wants to know who to ask for permission to do what, when. Their line management will be focused only on turnover of their portfolio, how many days delinquent it is. This is a shame, but a consequence of our modernist obsession with lean production management. It is all very well to set up your assembly line as if it were punting out Toyota Corollas, but your suppliers need to be on message, and generally they are not: the process is captive of fantastical terms imposed by Credit as per the above, rendered in language confected by legal, buffeted by the incommensurable frame of reference adopted by their counterparty and, more usually, its legal advisors.

- External legal counsel: The opposing side’s lawyers are mainly interested in showing how clever and useful they are to their client. This they can only do by changing the terms of your contract. This was first articulated in Büchstein’s articulation of legal existentialism: scribo, ergo sum.[3] Now, the more rigorously your baseline contract terms are benched to market, the less scope there is for mark-up: to be sure, one can never entirely rid a document of fussy clarifications and doubt-avoidance parentheticals, but you can minimise them by careful and elegant document design. But this rubs directly against Credit’s prerogative, above, which is to move the document as far from reality and towards the Platonic ideal of risk management as they can. This no-person’s land is an ideal playground for all the lawyers to mark-up, strike-out, thrust, parry and counter-thrust to their hearts’ consent. If the opposing sides pitch their tents five miles from each other, they cannot know when, whether or on what terms their respective minds will meet. Experience will say there is a fair chance they will meet, but exactly where will differ in ever case and, by the time they get there, the location will be shelled, pock-marked and riddled with bullet holes from the negotiation that it will resemble Berlin in 1946.

- Trading:

- Operations:

- Risk:

See also

References

- ↑ Hey hey, my my: rock ’n’ roll will never die, of course.

- ↑ For the obstreperous universe has a habit of playing tricks with people who are meant to know better. This is known as David Viniar’s, or Long-Term Capital Management’s folly.

- ↑ I mark-up, therefore I am