Simpson’s paradox: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

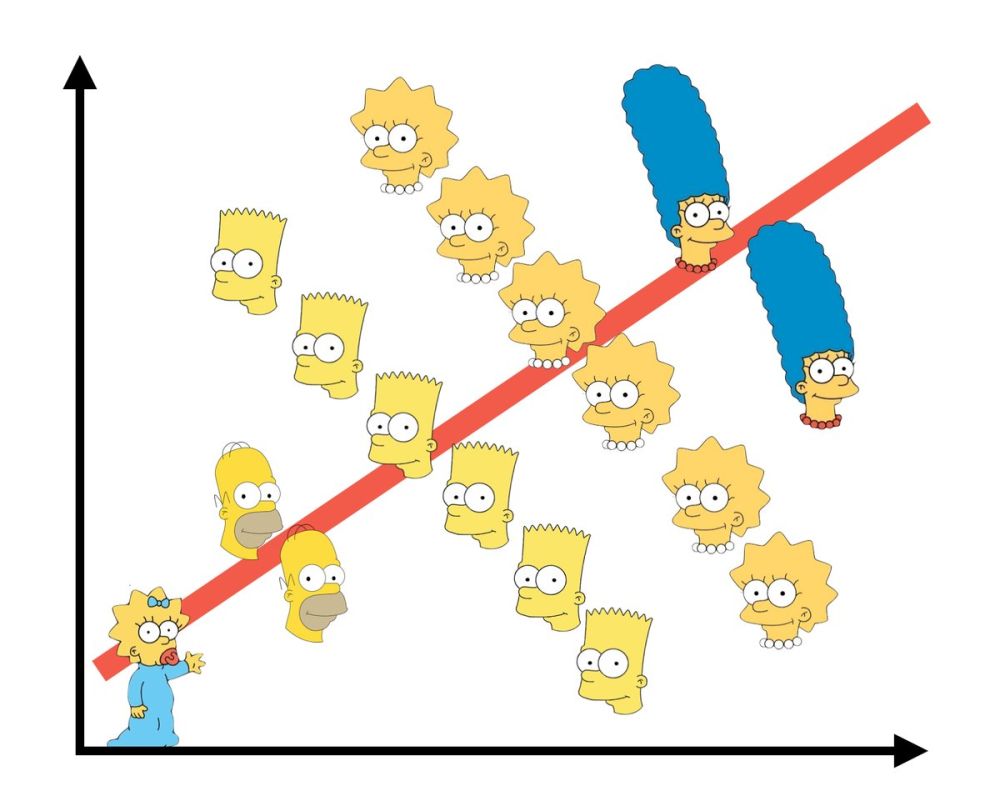

{{a|devil|}}[[ | {{a|devil|{{image|simpson paradox|jpg|Simpson’s paradox beautifully illustrated by [https://twitter.com/infowetrust/status/984536880199876608 @infowetrust on Twitter] yesterday.}}}}[[Simpson’s paradox]] is a statistical phenomenon where a trend that is apparent appears in several groups of related data, when viewed in isolation, disappears or reverses when the groups are combined. | ||

It plays particular havoc with social scientists when they try to draw [[causation|causal]] inferences — or moral imperatives — from data they have gathered with the careful intention of illustrating their own precious hypothesis. | It plays particular havoc with social scientists when they try to draw [[causation|causal]] inferences — or moral imperatives — from data they have gathered with the careful intention of illustrating their own precious hypothesis. | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

{{Sa}} | {{Sa}} | ||

*[[Correlation does not imply causation]] | *[[Correlation|Correlation does not imply causation]] | ||

*[[Multivariate factors]] | *[[Multivariate factors]] | ||

*[[Theory-dependence of observation]] | *[[Theory-dependence of observation]] | ||

{{Ref}} | {{Ref}} | ||

Latest revision as of 06:45, 1 May 2023

|

Simpson’s paradox is a statistical phenomenon where a trend that is apparent appears in several groups of related data, when viewed in isolation, disappears or reverses when the groups are combined.

It plays particular havoc with social scientists when they try to draw causal inferences — or moral imperatives — from data they have gathered with the careful intention of illustrating their own precious hypothesis.

This can upset, for example, eugenicists, craniometrists, and those who tend to the idea that a measure of “intelligence quotient” has any necessary bearing on practical intelligence, expected success in life[1] or personal value, let alone that it can be used to extrapolate into differences in intelligence between, say, races.

But it is equally offensive to those upset by Jordan Peterson and his fondness for pointing out how hard it is to draw firm conclusions — let alone moral ones — from any data set on which multiple, unrelated factors operate.

See also

References

- ↑ The best measure of success in life, of course, is “being alive”, and on that dimension, those of us on whom the midwife has attended but the reaper has not, are all equal.