Performative governance: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|devil|}}{{quote|“''I define performative governance as the state’s theatrical deployment of visual, verbal, and gestural symbols to foster an impression of good governance before an audience of citizens''” | {{a|devil| | ||

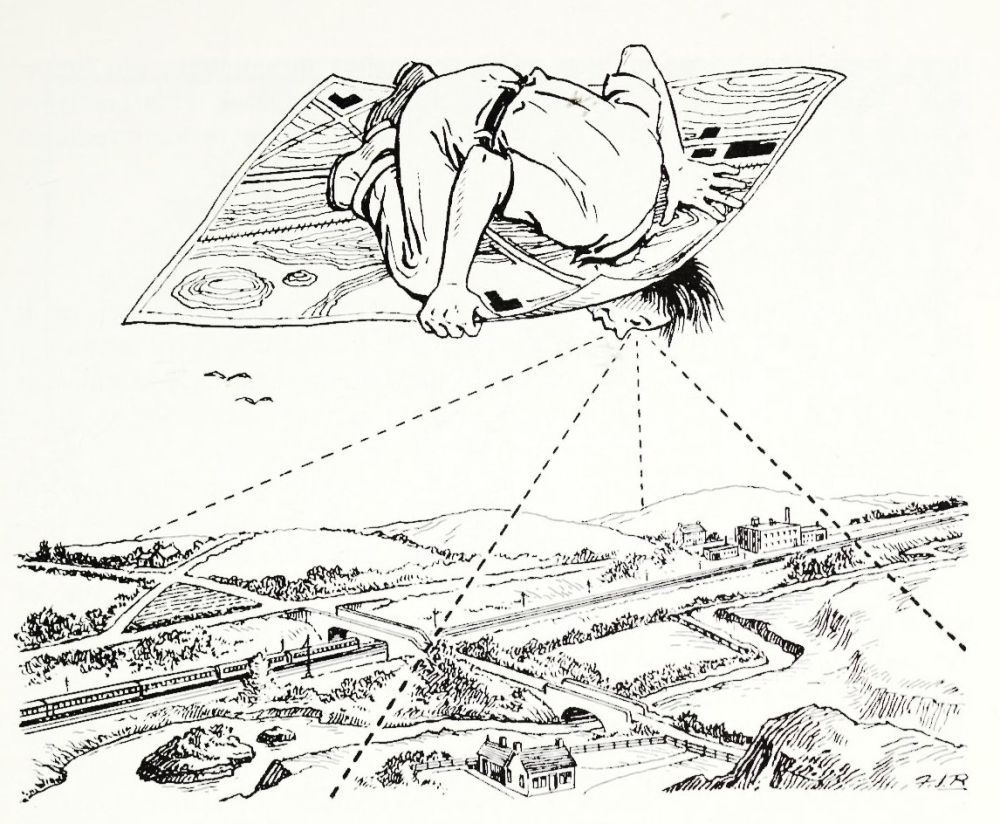

{{image|Map|jpg|}} | |||

}}{{quote|“''I define performative governance as the state’s theatrical deployment of visual, verbal, and gestural symbols to foster an impression of good governance before an audience of citizens''” | |||

:—Iza Ding<ref>''World Politics'', [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-politics/article/abs/performative-governance/AAC558378BEA651DB7E2480ECFFB4E10 Vol 72, Issue 4, October 2020, pp. 525 - 556. ] “Performative governance should be distinguished from other types of state behavior, such as inertia, paternalism, and the substantive satisfaction of citizens’ demands.”</ref>}} | :—Iza Ding<ref>''World Politics'', [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-politics/article/abs/performative-governance/AAC558378BEA651DB7E2480ECFFB4E10 Vol 72, Issue 4, October 2020, pp. 525 - 556. ] “Performative governance should be distinguished from other types of state behavior, such as inertia, paternalism, and the substantive satisfaction of citizens’ demands.”</ref>}} | ||

Just as well this kind of thing could never happen in a corporate environment. | Just as well this kind of thing could never happen in a corporate environment. | ||

“[[Performative]]” is a vogue word, and if the learned author thinks she’s discovered something new — that administrators manage [[second-order derivative]]s and [[Proxy|proxies]] of their political problems rather than engaging in the political problems themselves — she would do herself a favour by reading {{author|James C. Scott}}, {{author|Jane Jacobs}}, {{author|W. Edwards Deming}}, {{author|Jane Jacobs}} and others who have been articulating these ideas for seventy or more years — but ''since'' it’s fashionable, and since it ''is'' bang-on the money, let’s go with it. | |||

With — perhaps — a spin. You “perform” governance, generally, by ''approximating'' it: creating crude, two-dimensional stick-figure illustrations of a four-dimensional<ref>Yes: ''four'', and I don’t even need to exceed Euclidean geometry to get there: governance propositions mutate over ''time''.</ref> reality which is genuinely ineffable: with social systems there is never the necessary information, nor boundaries, for any simplistic representation to work. It is literally boundless and indeterminate. | |||

Modern administration is not “performative” in the sense of being ''fictional'', but irresponsibly ''representational'': the [[modernist]] sees everyday calamity as a bug, not a feature: a function of low-level human failure: as ''[[The Field Guide to Human Error Investigations|operator error]]''. | |||

If the errors, inconstancies and misapprehensions of human frailty could only be removed, then — on this view — orderly good governance would surely follow. Thus; administrators are never to blame: it’s the [[meatware]]. | |||

But then, why pay the big bucks to middle managers? This kind of administration is easy: you just have to weed out the bad apples, and blame the ones you missed. Your administrative role is reduced to one of [[human resources]].<ref>Thinks: ''waaaaaaaait a minute.''</ref> | |||

The contrary view is that administration is ''hard''. Avoiding [[system accidents]], designing processes and products; aligning incentives, reacting to subtle, and sudden, shifts in the business environment; fixing conflicts of interest: these are ''ongoing'' tasks that need constant attention, interaction and adjustment, nudging the steering-wheel; dabbing the breaks, de-clutching at the bottom of the hill — and these are solely the responsibility of management. If there is a calamity at the coal face, that is ''[[prima facie]]'' indication that ''management'' has failed, because it has put the wrong person, with the wrong tools, in the wrong place. You had one job, and that was it. | |||

Curiously, management orthodoxy leans to the former view. For the life of me I can’t think why. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Grand unifying theory]] | |||

*{{fieldguide}} | |||

*[[Reduction in force]] | |||

*{{br|Seeing Like a State}} | *{{br|Seeing Like a State}} | ||

*[[The map and the territory]] | |||

*[[Box-ticking]] | *[[Box-ticking]] | ||

{{ref}} | {{ref}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:51, 15 June 2023

|

|

“I define performative governance as the state’s theatrical deployment of visual, verbal, and gestural symbols to foster an impression of good governance before an audience of citizens”

- —Iza Ding[1]

Just as well this kind of thing could never happen in a corporate environment.

“Performative” is a vogue word, and if the learned author thinks she’s discovered something new — that administrators manage second-order derivatives and proxies of their political problems rather than engaging in the political problems themselves — she would do herself a favour by reading James C. Scott, Jane Jacobs, W. Edwards Deming, Jane Jacobs and others who have been articulating these ideas for seventy or more years — but since it’s fashionable, and since it is bang-on the money, let’s go with it.

With — perhaps — a spin. You “perform” governance, generally, by approximating it: creating crude, two-dimensional stick-figure illustrations of a four-dimensional[2] reality which is genuinely ineffable: with social systems there is never the necessary information, nor boundaries, for any simplistic representation to work. It is literally boundless and indeterminate.

Modern administration is not “performative” in the sense of being fictional, but irresponsibly representational: the modernist sees everyday calamity as a bug, not a feature: a function of low-level human failure: as operator error.

If the errors, inconstancies and misapprehensions of human frailty could only be removed, then — on this view — orderly good governance would surely follow. Thus; administrators are never to blame: it’s the meatware.

But then, why pay the big bucks to middle managers? This kind of administration is easy: you just have to weed out the bad apples, and blame the ones you missed. Your administrative role is reduced to one of human resources.[3]

The contrary view is that administration is hard. Avoiding system accidents, designing processes and products; aligning incentives, reacting to subtle, and sudden, shifts in the business environment; fixing conflicts of interest: these are ongoing tasks that need constant attention, interaction and adjustment, nudging the steering-wheel; dabbing the breaks, de-clutching at the bottom of the hill — and these are solely the responsibility of management. If there is a calamity at the coal face, that is prima facie indication that management has failed, because it has put the wrong person, with the wrong tools, in the wrong place. You had one job, and that was it.

Curiously, management orthodoxy leans to the former view. For the life of me I can’t think why.

See also

- Grand unifying theory

- Sidney Dekker’s The Field Guide to Human Error Investigations

- Reduction in force

- Seeing Like a State

- The map and the territory

- Box-ticking

References

- ↑ World Politics, Vol 72, Issue 4, October 2020, pp. 525 - 556. “Performative governance should be distinguished from other types of state behavior, such as inertia, paternalism, and the substantive satisfaction of citizens’ demands.”

- ↑ Yes: four, and I don’t even need to exceed Euclidean geometry to get there: governance propositions mutate over time.

- ↑ Thinks: waaaaaaaait a minute.