Mediocrity drift: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|hr|}}{{d|{{PAGENAME}}|/ˌmiːdɪˈɒkrɪti drɪft/|n}} | {{a|hr|{{image|Replacement cost of lateral quitter|png|}}}}{{Quote| | ||

“The bank emphasizes that staff will also be reduced through [[natural attrition]], not filling vacant positions or offering early retirement.” | |||

:— ''[https://www.finews.com/news/english-news/54951-credit-suisse-job-cuts-restructuring-personnel-costs Credit Suisse Job Cuts are Causing Unrest]'', finews.com, December 2022}}{{d|{{PAGENAME}}|/ˌmiːdɪˈɒkrɪti drɪft/|n}} | |||

A curious, unintended, negative feedback loop of lazy [[human capital management]]. If you don’t proactively ''retain'' good staff, and if you don’t actively manage out poor staff — if you manage by tactical hiring and “[[natural attrition]]” — the general quality of your staff ''relative to their cost'' will ''decline''. | |||

This is a logical consequence of this style of management, at least if you accept four general assumptions: | |||

''Good staff leave by themselves'': Staff with [[Lateral quitter|the gumption to leave]] tend to be good employees, ''relative to what you pay them''. These people are, therefore, ''necessarily'' underpaid. No surprise: that’s why they’re leaving. | |||

''Bad staff don’t'': Conversely, those who are already overpaid for what they do tend not to quit, because they know are already onto a good thing. These staff ''may'' leave, but only to join an employer even more gullible that you. Otherwise, they won’t leave ''unless you make them'', by performance management or through a [[RIF]]. These people, therefore, are generally ''overpaid''. That’s why they stay. | |||

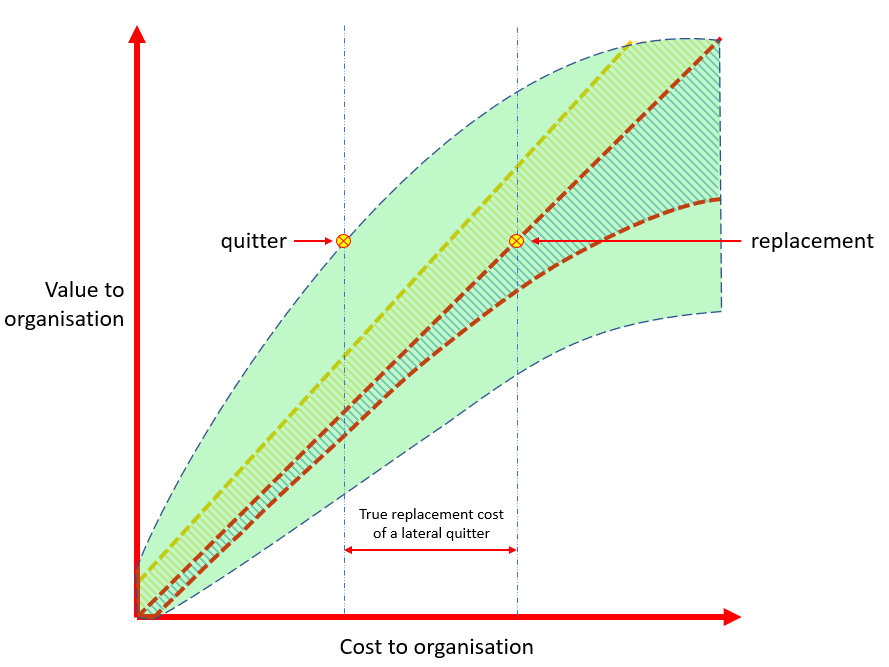

''You have to pay lateral hires the market rate'': When you replace leavers, you have to pay the market rate. If the person leaving was underpaid relative to the market, you have two choices: pay more for her replacement, or hire a less experienced replacement. Either way, you are getting someone who is paid at their own cost-value threshold. | |||

''Subgroups are normally distributed'': That the ''equilibrium'' value of your personnel is normally distributed around the cost-value threshold, and so is that of each subgroup of your personnel however chosen. So, you will have as many good staff as you do bad ones. And you’ll have as many good compliance staff as you do bad ones, and as many good left-handers as bad ones, and young, old, men, women and so on. Each such group will ''within their own group'' have broadly similar distributions of outperformers and plodders. (This is simply assuming that the law of averages applies). | |||

Now we can see a negative feedback loop here. If all people you hire have an equal chance of working out well — their relative competence is evenly distributed — and those who outperform are likely to quit while those who disappoint are likely to stay, over time, the competency of your workforce will skew ''mediocre''. | |||

Call this “mediocrity drift”. | |||

Outperforming quitters will be replaced — at necessarily greater cost, [[Ceteris paribus|''ceteris paribus'']], because the one and only time you are obliged to [[mark to market]] is when you hire — by those having no institutional knowledge, no internal network, and even controlling for that, only an “evens” chance of working out well. | |||

===System effects=== | |||

Here is [[systemantics]] in its natural state. How incoming [[Lateral hire|lateral hires]] perform will remain to be seen but, remember, performance is measured relative to cost. One firm’s incoming lateral hire is another firm’s lateral quitter. An outperforming [[lateral quitter]] marks herself to market, gets a pay-rise (why else leave?) and enters her new firm at the [[cost-value threshold]]. When she pitches up, she is no longer an outperformer. True, she may turn out that way, but it is not certain. She is just as likely — presuming a normal distribution again — to underperform. | |||

Secondly, notice how pernicious the idea of the ''average'' is here. | |||

===Affirmative action bummer=== | |||

If so, then a system that, to correct a perceived imbalance between groups, favours one (Group A) over another (Group B), will have a counterintuitive effect on the ''average'' quality of both groups: the ''un''favoured group will ''increase'' in average quality through attrition, and the favoured group will ''decrease'' in average quality, through a lack of it, ''even though no individual performance, in either group, changes''. | |||

On ''average'', Group A is paid progressively less. It looks like Group A members are being systematically discriminated against on pay, but this is a misleading artefact of [[averagarianism]] (Individually, ''no one’s'' pay changes). Group A members are being ''favoured for poor performance''. | |||

On a second glance, you can see why this should be so. The process systematically weeds out ''underperforming'' members of unfavoured Group B, by culling them, and ''overperforming'' members of Group A — they will leave of their own will just like any outperformer. The “good” side of the distribution will progressively become Group B-dominated — they are not being bid away as frequently — and the “below par” section will become progressively Group A-dominated, as poor-performing Group B members are culled ahead of those from Group A. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Lateral quitter]] | *[[Lateral quitter]] | ||

*[[Reduction in force]] | *[[Reduction in force]] | ||

*[[Competence phase transition]] | *[[Competence phase transition]] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:23, 8 February 2024

|

The Human Resources military-industrial complex

|

“The bank emphasizes that staff will also be reduced through natural attrition, not filling vacant positions or offering early retirement.”

- — Credit Suisse Job Cuts are Causing Unrest, finews.com, December 2022

Mediocrity drift

/ˌmiːdɪˈɒkrɪti drɪft/ (n.)

A curious, unintended, negative feedback loop of lazy human capital management. If you don’t proactively retain good staff, and if you don’t actively manage out poor staff — if you manage by tactical hiring and “natural attrition” — the general quality of your staff relative to their cost will decline.

This is a logical consequence of this style of management, at least if you accept four general assumptions:

Good staff leave by themselves: Staff with the gumption to leave tend to be good employees, relative to what you pay them. These people are, therefore, necessarily underpaid. No surprise: that’s why they’re leaving.

Bad staff don’t: Conversely, those who are already overpaid for what they do tend not to quit, because they know are already onto a good thing. These staff may leave, but only to join an employer even more gullible that you. Otherwise, they won’t leave unless you make them, by performance management or through a RIF. These people, therefore, are generally overpaid. That’s why they stay.

You have to pay lateral hires the market rate: When you replace leavers, you have to pay the market rate. If the person leaving was underpaid relative to the market, you have two choices: pay more for her replacement, or hire a less experienced replacement. Either way, you are getting someone who is paid at their own cost-value threshold.

Subgroups are normally distributed: That the equilibrium value of your personnel is normally distributed around the cost-value threshold, and so is that of each subgroup of your personnel however chosen. So, you will have as many good staff as you do bad ones. And you’ll have as many good compliance staff as you do bad ones, and as many good left-handers as bad ones, and young, old, men, women and so on. Each such group will within their own group have broadly similar distributions of outperformers and plodders. (This is simply assuming that the law of averages applies).

Now we can see a negative feedback loop here. If all people you hire have an equal chance of working out well — their relative competence is evenly distributed — and those who outperform are likely to quit while those who disappoint are likely to stay, over time, the competency of your workforce will skew mediocre.

Call this “mediocrity drift”.

Outperforming quitters will be replaced — at necessarily greater cost, ceteris paribus, because the one and only time you are obliged to mark to market is when you hire — by those having no institutional knowledge, no internal network, and even controlling for that, only an “evens” chance of working out well.

System effects

Here is systemantics in its natural state. How incoming lateral hires perform will remain to be seen but, remember, performance is measured relative to cost. One firm’s incoming lateral hire is another firm’s lateral quitter. An outperforming lateral quitter marks herself to market, gets a pay-rise (why else leave?) and enters her new firm at the cost-value threshold. When she pitches up, she is no longer an outperformer. True, she may turn out that way, but it is not certain. She is just as likely — presuming a normal distribution again — to underperform.

Secondly, notice how pernicious the idea of the average is here.

Affirmative action bummer

If so, then a system that, to correct a perceived imbalance between groups, favours one (Group A) over another (Group B), will have a counterintuitive effect on the average quality of both groups: the unfavoured group will increase in average quality through attrition, and the favoured group will decrease in average quality, through a lack of it, even though no individual performance, in either group, changes.

On average, Group A is paid progressively less. It looks like Group A members are being systematically discriminated against on pay, but this is a misleading artefact of averagarianism (Individually, no one’s pay changes). Group A members are being favoured for poor performance.

On a second glance, you can see why this should be so. The process systematically weeds out underperforming members of unfavoured Group B, by culling them, and overperforming members of Group A — they will leave of their own will just like any outperformer. The “good” side of the distribution will progressively become Group B-dominated — they are not being bid away as frequently — and the “below par” section will become progressively Group A-dominated, as poor-performing Group B members are culled ahead of those from Group A.