Pace layering: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|bi| | {{a|bi|{{image|Pace layering|jpg|}}}}{{Quote|In Europe you can see it in terminology, where the names of months (governance) have varied radically since 1500, but the names of signs of the Zodiac (culture) are unchanged in millennia. Europe’s most intractable wars have been religious wars. | ||

:—{{author|Stewart Brand}}, ''Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning''<ref>https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/issue3-brand/release/2</ref>}} | |||

{{Quote|In Europe you can see it in terminology, where the names of months (governance) have varied radically since 1500, but the names of signs of the Zodiac (culture) are unchanged in millennia. Europe’s most intractable wars have been religious wars. | |||

Stewart | |||

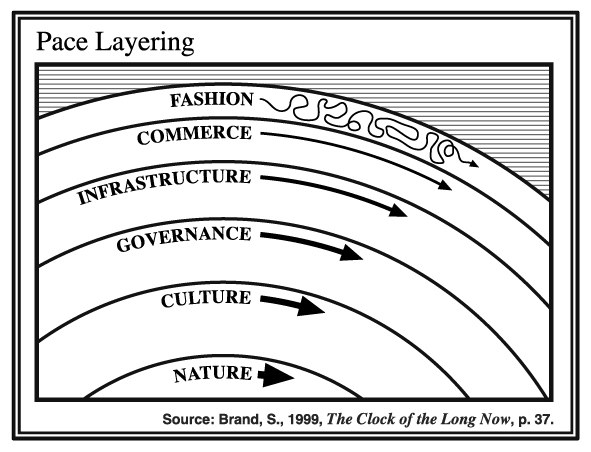

{{author|Stewart Brand}}’s ''pace layering'' concept, which evidently he developed in a collaboration with Brian Eno, explains the resilience of a [[complex system]], how it resists shocks and how it adapts over time by the [[metaphor]] of “layers” of which the system is comprised, and that operate at different scales and at different rates of change. It also acknowledges that such systems are not hermetically-sealed clockwork engines, but rather amorphous, boundary-less ephemeral contrivances that borrow from or depend on, ''other'' pre-existing systems with their own dependencies. | |||

Brand described six layers. From the bottom up: ''nature'', ''culture'', ''governance'', ''infrastructure'', ''commerce'' and ''fashion''. To work through these, let’s take the example of a single market. | |||

=== Layers=== | |||

“'''Nature'''” describes the most universal, fundamental, difficult-to-fiddle-with engineering of the system, on which all other levels depend. Nature applies universally, well beyond the scope of the individual market in our example. It includes biology, chemistry, physics, meteorology, geology to the extent these determine how the participants behave, and are impacted by the behaviour of participants in the market. The market may generate changes in nature (as to life expectancy, crop yield, climate and so on) but they happen over extremely long time scales and would require concerted effort amongst many different markets. It may not change very fast, but nature is highly determinative of what a market can and cannot do. | |||

So to understand how deep and persistent a system effect is and how fixable it is, consider the level are which it presents. A local gang conflict can fix easily, a religious grievance | “'''Culture'''” is the next layer. This is not biologically determined, but is nonetheless deeply wired into the behaviour and expectations of different ''peoples''. It is wider, and deeper, than a national affiliation. Europeans are generally different, cultural from Anglo Saxons, within whom American Anglo Saxons are different from the English, who are different from the Scots, Welsh the Irish; Mediterranean Europeans are culturally different from Alpine Europeans, those from the Balkans, Slavics, Scandinavians and so on. A market which might work in Belgium or Holland might fail in the Hebrides. The boundaries between these cultures are not fixed, they merge and shift where they intersect and will gradually change, especially with immigration through time. | ||

“'''Governance'''”, which is wider than government, but surely includes it. Can include social governance, especially where dedicated to preserving historical ways of life (the National Trust) and also the traces of governance, such as property parcels, highways and so on. Thus after the Great Fire of London King Charles sought proposals use this rare chance to entirely remodel London. Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren were among those who submitted plans, Wren’s influenced by Paris’ wide avenues hubbing from Rome-style piazzas, while Hooke suggested a grid that would anticipate Manhattan’s grid layout by 150 years.<ref>https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-35418272</ref> But all proved impossible, and London was rebuilt on its existing footprint because resolving the underlying land ownership issues in order to meaningfully change the city layout was to complicated and expensive. Governance resisted change. | |||

“'''Infrastructure'''” is a step easier to fix, but still requires commitment over a time horizon too long for individuals or corporations matching to the cadence of the quarterly results. We see here how culture Influences infrastructural appetite: the American cultural commitment to communally-owned infrastructure (epecially transport, healthcare, and to a degree education) is markedly weaker than the European one (or even the British one). | |||

{{Quote|“Infrastructure, essential as it is, can’t be justified in strictly commercial terms. The payback period for things such as transportation and communication systems is too long for standard investment.”<ref>Brand, ibid</ref>}} | |||

“'''Commerce'''” ''does'' march to the cadence of the quarterly earnings report, and fights off competing products, market development and customers who are influenced by fashionable views. | |||

“'''Fashion'''” is ephemeral, random, dynamic, fluctuating, noisy — in the sense of “loud” and in the sense of “obscuring signal” — but even this can effect the adjacent layers if persistent through time. | |||

=== Pace === | |||

The rate at which the successive layers change, and the scale at which the change operates differs. Change happens most slowly and most universally at the bottom: | |||

'''Nature''' affects a ''species'', but changes at a glacial, evolutionary pace. As this changes, the more transient layers above change, on a faster cycle, to accommodate it. Doorways and ceilings are higher than they were a thousand years ago, because development in diet and nutrition has led to taller humans. | |||

'''Culture''' affects a ''people'', which is a deeper and more fundamental grouping than a ''nation.'' There are commonalities in outlook, values and way of life between the Alpine people of Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France and Italy that are not shared by others from those countries. Values and customs change, but gradually, and while they may be influenced over generations by migratory patterns, cultural conflicts, shifts in technology, government, and even fashion, these influences must persist for long periods before they permanently affect the deep cultural preferences and values. | |||

Governance is of a nation, infrastructure a city, business a market and fashion whoever likes it. The fastest layers are the most innovative: the slowest are the most stable. | |||

Fast layers learn. Slow layers remember. | |||

===What are not layers === | |||

''[[Technology]] is not a layer'' but operates across the spectrum at different layers, which means you should be careful, [[legaltechbro]]s, to consider where your application fits in.<ref>[https://open.spotify.com/episode/6cjjZ4mjKHcEfOHraLimzb? Stewart Brand and Paul Saffo, ''Pace Layers Thinking''] (about 38 minutes in).</ref> | |||

Nor is art, which may be shallow as fashion or as deep as culture, but may be a device for reimagining any of the components (cave art and mythology deep; flared trousers and hula-hoops shallow) | |||

There are resonances here with the the [[end-to-end principle]] of network architecture — Brand describes [[complex adaptive system]]s in terms of social structures successive layers. For the internet that is its packet-switching basic layer; for a society it may be chemistry, physics, and biology. The essential way everything is wired. Brand calls this “nature”. To change this is profoundly difficult — any change you make can fundamentally break any layer that depends on it — so any changes that do happen very slowly and deliberately. | |||

{{Quote|''“Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.”''}} | |||

So to understand how deep and persistent a [[system effect]] is and how fixable it is, consider the level are which it presents. A local gang conflict can fix easily, a religious grievance won’t. | |||

If an issue presents as a matter of ''fashion'' but proves inexplicably resistant to change, it may be an indication that it is really operates at a deeper level. | |||

Why don’t lawyers adopt [[plain English]]? Why don’t they adopt legal technology?<ref>This begs the question that lawyers ''don’t'' adopt technology: we make the argument elsewhere that they absolutely do; they simply don’t adopt ''bad'' or ''shamelessly expensive'' technology.</ref> If we regard as a matter of professional preference what is actually deep articulation of the [[agency problem]], and a requirement of the [[power structure]] (the “legal paradigm” depends on punters believing what lawyers so is all tremendously complicated and difficult) — then trying to change that through peer pressure within that power structure will not work. The challenge may come at a cc deeper level, and from someone necessarily ''outside'' the paradigm, providing an imagined alternative to users of the services that those within the paradigm can’t see. | |||

This is a good on the paradigm. It’s not just how deeply buried the assumption, but it’s layer. | |||

{{Ref}} | {{Ref}} | ||

<references /> | |||

Latest revision as of 17:17, 4 November 2023

|

The JC’S favourite Big Ideas™

|

In Europe you can see it in terminology, where the names of months (governance) have varied radically since 1500, but the names of signs of the Zodiac (culture) are unchanged in millennia. Europe’s most intractable wars have been religious wars.

- —Stewart Brand, Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning[1]

Stewart Brand’s pace layering concept, which evidently he developed in a collaboration with Brian Eno, explains the resilience of a complex system, how it resists shocks and how it adapts over time by the metaphor of “layers” of which the system is comprised, and that operate at different scales and at different rates of change. It also acknowledges that such systems are not hermetically-sealed clockwork engines, but rather amorphous, boundary-less ephemeral contrivances that borrow from or depend on, other pre-existing systems with their own dependencies.

Brand described six layers. From the bottom up: nature, culture, governance, infrastructure, commerce and fashion. To work through these, let’s take the example of a single market.

Layers

“Nature” describes the most universal, fundamental, difficult-to-fiddle-with engineering of the system, on which all other levels depend. Nature applies universally, well beyond the scope of the individual market in our example. It includes biology, chemistry, physics, meteorology, geology to the extent these determine how the participants behave, and are impacted by the behaviour of participants in the market. The market may generate changes in nature (as to life expectancy, crop yield, climate and so on) but they happen over extremely long time scales and would require concerted effort amongst many different markets. It may not change very fast, but nature is highly determinative of what a market can and cannot do.

“Culture” is the next layer. This is not biologically determined, but is nonetheless deeply wired into the behaviour and expectations of different peoples. It is wider, and deeper, than a national affiliation. Europeans are generally different, cultural from Anglo Saxons, within whom American Anglo Saxons are different from the English, who are different from the Scots, Welsh the Irish; Mediterranean Europeans are culturally different from Alpine Europeans, those from the Balkans, Slavics, Scandinavians and so on. A market which might work in Belgium or Holland might fail in the Hebrides. The boundaries between these cultures are not fixed, they merge and shift where they intersect and will gradually change, especially with immigration through time.

“Governance”, which is wider than government, but surely includes it. Can include social governance, especially where dedicated to preserving historical ways of life (the National Trust) and also the traces of governance, such as property parcels, highways and so on. Thus after the Great Fire of London King Charles sought proposals use this rare chance to entirely remodel London. Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren were among those who submitted plans, Wren’s influenced by Paris’ wide avenues hubbing from Rome-style piazzas, while Hooke suggested a grid that would anticipate Manhattan’s grid layout by 150 years.[2] But all proved impossible, and London was rebuilt on its existing footprint because resolving the underlying land ownership issues in order to meaningfully change the city layout was to complicated and expensive. Governance resisted change.

“Infrastructure” is a step easier to fix, but still requires commitment over a time horizon too long for individuals or corporations matching to the cadence of the quarterly results. We see here how culture Influences infrastructural appetite: the American cultural commitment to communally-owned infrastructure (epecially transport, healthcare, and to a degree education) is markedly weaker than the European one (or even the British one).

“Infrastructure, essential as it is, can’t be justified in strictly commercial terms. The payback period for things such as transportation and communication systems is too long for standard investment.”[3]

“Commerce” does march to the cadence of the quarterly earnings report, and fights off competing products, market development and customers who are influenced by fashionable views.

“Fashion” is ephemeral, random, dynamic, fluctuating, noisy — in the sense of “loud” and in the sense of “obscuring signal” — but even this can effect the adjacent layers if persistent through time.

Pace

The rate at which the successive layers change, and the scale at which the change operates differs. Change happens most slowly and most universally at the bottom:

Nature affects a species, but changes at a glacial, evolutionary pace. As this changes, the more transient layers above change, on a faster cycle, to accommodate it. Doorways and ceilings are higher than they were a thousand years ago, because development in diet and nutrition has led to taller humans.

Culture affects a people, which is a deeper and more fundamental grouping than a nation. There are commonalities in outlook, values and way of life between the Alpine people of Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France and Italy that are not shared by others from those countries. Values and customs change, but gradually, and while they may be influenced over generations by migratory patterns, cultural conflicts, shifts in technology, government, and even fashion, these influences must persist for long periods before they permanently affect the deep cultural preferences and values.

Governance is of a nation, infrastructure a city, business a market and fashion whoever likes it. The fastest layers are the most innovative: the slowest are the most stable.

Fast layers learn. Slow layers remember.

What are not layers

Technology is not a layer but operates across the spectrum at different layers, which means you should be careful, legaltechbros, to consider where your application fits in.[4]

Nor is art, which may be shallow as fashion or as deep as culture, but may be a device for reimagining any of the components (cave art and mythology deep; flared trousers and hula-hoops shallow)

There are resonances here with the the end-to-end principle of network architecture — Brand describes complex adaptive systems in terms of social structures successive layers. For the internet that is its packet-switching basic layer; for a society it may be chemistry, physics, and biology. The essential way everything is wired. Brand calls this “nature”. To change this is profoundly difficult — any change you make can fundamentally break any layer that depends on it — so any changes that do happen very slowly and deliberately.

“Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous. Fast and small instructs slow and big by accrued innovation and by occasional revolution. Slow and big controls small and fast by constraint and constancy. Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.”

So to understand how deep and persistent a system effect is and how fixable it is, consider the level are which it presents. A local gang conflict can fix easily, a religious grievance won’t.

If an issue presents as a matter of fashion but proves inexplicably resistant to change, it may be an indication that it is really operates at a deeper level.

Why don’t lawyers adopt plain English? Why don’t they adopt legal technology?[5] If we regard as a matter of professional preference what is actually deep articulation of the agency problem, and a requirement of the power structure (the “legal paradigm” depends on punters believing what lawyers so is all tremendously complicated and difficult) — then trying to change that through peer pressure within that power structure will not work. The challenge may come at a cc deeper level, and from someone necessarily outside the paradigm, providing an imagined alternative to users of the services that those within the paradigm can’t see.

This is a good on the paradigm. It’s not just how deeply buried the assumption, but it’s layer.

References

- ↑ https://jods.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/issue3-brand/release/2

- ↑ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-35418272

- ↑ Brand, ibid

- ↑ Stewart Brand and Paul Saffo, Pace Layers Thinking (about 38 minutes in).

- ↑ This begs the question that lawyers don’t adopt technology: we make the argument elsewhere that they absolutely do; they simply don’t adopt bad or shamelessly expensive technology.