Labour theory of value: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|devil|}}:“''The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.''” | {{a|devil| | ||

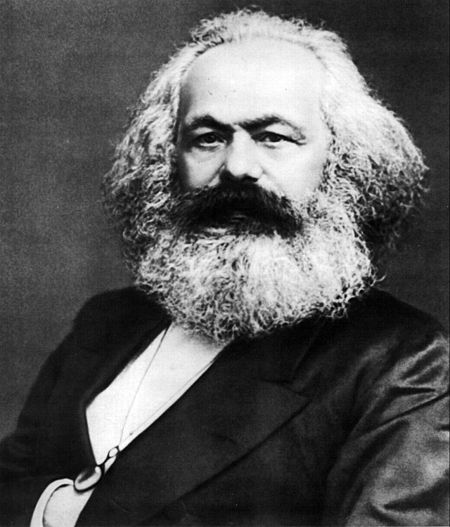

[[File:Karl Marx.jpg|450px|thumb|center|A fan of hard yakka, yesterday.]] | |||

}}:“''The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.''” | |||

::{{author|Adam Smith}} —{{br|The Wealth of Nations}}, Book 1, chapter IV. | ::{{author|Adam Smith}} —{{br|The Wealth of Nations}}, Book 1, chapter IV. | ||

The [[labour theory of value]] (“'''[[LTV]]'''”) argues that the ''economic'' value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of “socially necessary labour” required to produce it. A staple of Marxist theory, | The [[labour theory of value]] (“'''[[LTV]]'''”) argues that the ''economic'' value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of “socially necessary labour” required to produce it. A staple of Marxist theory, the [[LTV]] stands in contrast to the neoclassical model of [[value]] — the one typically subscribed to by venal capitalist running dogs etc. — that the value of a good or service is ''whatever someone else is prepared to pay for it''. | ||

Cue | Cue long-winded diatribes, from either side, about those who know the ''price'' of everything, the ''value'' of nothing, and so forth. But it seems to me that “''price''” — an identifiable fact: the number at which you both arrived — and “''value''”: the buyer’s and seller’s respective opinions about the thing they have just bought and sold — ''cannot'' be the same thing; indeed the commercial world ''depends'' upon their very difference. The overall rationale for a transaction between rational merchants must be that the seller values the property ''below'' the agreed price, and the buyer ''above'' it. If [[monetisation|monetising]] an asset, or converting money into an asset<Ref>Why isn’t there a word like “monetisation” for the inverse process?</ref> is some kind of phase transition, then the process involves a loss of energy, an increase in entropy, and a rational agent would not [[monetise]] or [[assetisation|assetise]] at a price ''exactly equal'' to its own value assessment. Hence, rational agents will only transact when ''both'' of them believe they are creating value. This beautiful dissonance is why economics is not a zero-sum game. As long as merchants are providing valuable [[consideration]] for their exchanges, there should be no tragedy on the commons.<ref>This is just one good argument for freely sharing intellectual property. It is not not an exhaustible resource. What other people do with your IP can benefit everyone.</ref> | ||

In any case, [[reg tech]] providers are wont to unexpectedly invoke the [[labour theory of value]] on prospective clients by way of justifying the outrageous rent they propose to extract: “this desultry code, which I commissioned from some java programmer in the Balkans I found on UpWork and which he knocked together over a weekend, will save you a million dollars a year in legal fees. Therefore you will be thrilled to hear that your licence is only $500,000 per annum, for up to 100 documents per quarter.” | In any case, [[reg tech]] providers are wont to unexpectedly invoke the [[labour theory of value]] on prospective clients by way of justifying the outrageous rent they propose to extract: “this desultry code, which I commissioned from some java programmer in the Balkans I found on ''UpWork'' and which he knocked together over a weekend, will save you a million dollars a year in legal fees. Therefore you will be thrilled to hear that your licence is only $500,000 per annum, for up to 100 documents per quarter.” | ||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[ClauseHub: theory]] | *[[ClauseHub: theory]] | ||

Revision as of 19:36, 6 February 2021

|

- “The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and, on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use. Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything; scarce anything can be had in exchange for it. A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it.”

- Adam Smith —The Wealth of Nations, Book 1, chapter IV.

The labour theory of value (“LTV”) argues that the economic value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of “socially necessary labour” required to produce it. A staple of Marxist theory, the LTV stands in contrast to the neoclassical model of value — the one typically subscribed to by venal capitalist running dogs etc. — that the value of a good or service is whatever someone else is prepared to pay for it.

Cue long-winded diatribes, from either side, about those who know the price of everything, the value of nothing, and so forth. But it seems to me that “price” — an identifiable fact: the number at which you both arrived — and “value”: the buyer’s and seller’s respective opinions about the thing they have just bought and sold — cannot be the same thing; indeed the commercial world depends upon their very difference. The overall rationale for a transaction between rational merchants must be that the seller values the property below the agreed price, and the buyer above it. If monetising an asset, or converting money into an asset[1] is some kind of phase transition, then the process involves a loss of energy, an increase in entropy, and a rational agent would not monetise or assetise at a price exactly equal to its own value assessment. Hence, rational agents will only transact when both of them believe they are creating value. This beautiful dissonance is why economics is not a zero-sum game. As long as merchants are providing valuable consideration for their exchanges, there should be no tragedy on the commons.[2]

In any case, reg tech providers are wont to unexpectedly invoke the labour theory of value on prospective clients by way of justifying the outrageous rent they propose to extract: “this desultry code, which I commissioned from some java programmer in the Balkans I found on UpWork and which he knocked together over a weekend, will save you a million dollars a year in legal fees. Therefore you will be thrilled to hear that your licence is only $500,000 per annum, for up to 100 documents per quarter.”