Discourse on Intercourse

|

Discourse on Intercourse is a well-meant though basically wrong-headed philosophical tract formulated by delusional librettist Otto Büchstein in the depths of dengue fever delirium in 1769. It immediately preceded — and some say influenced — his last, great unfinished play Die Schweizer Heulsuse.

Conference call epistemology

Outraged by René Descartes suggestion in 1637 that the only indubitable thing in the universe was one’s own existence, Büchstein set out to deduce an entire multi-personal epistemology from the commercial inevitability of conference calls.

Büchstein’s logic was this: all-hands conference calls must exist, since no-one in her right mind would make up such a horrendous idea if she didn’t have to. So, since someone has had such an idea, conference calls must therefore exist as a necessary, indubitable, fact of corporate life.

On that predicate, it follows as an a priori fact that since a conference call must comprise more than one person (“a man cannot meet alone”, Büchstein was fond of quipping), for conference calls to be possible one’s most basic irreducible ontology implies that universe must contain not just one but multiple individuals.

At least three, thought Büchstein: the “meetor” (which he regarded as an analog of Descartes’ “thinking thing”, or res cogitans), one “meetee” (which Büchstein characterised primarily as a “talking thing” (res verbositans) and since, transparently neither of these homunculi would willingly meet without there being some kind of compulsion to do so, a third person (a management consultant or project manager of some kind) to ensure the meeting happens, that minutes are taken, actions assigned and timelines “agreed” for “action closure” (this third person Büchstein called an “action-assigning thing” or res bossitans).

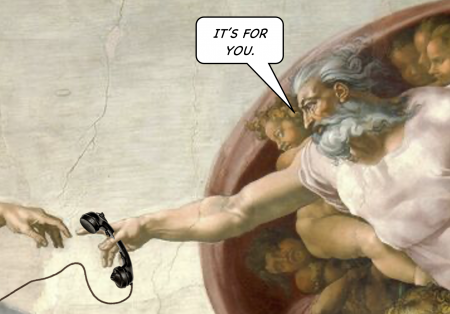

In any case, since they were all engaged on a conference call, none of them needed to be, or indeed could be, God. Buchstein arrived at this conclusion with the following reasoning:

“God is omniscient,” Büchstein said. “Therefore, God doesn’t do conference calls. What would be the point? God already knows everything. And, come to think of it, God is also omnipotent. It is, as I have said, axiomatic that no one goes on a conference call that she is not obliged to. Since there is no way of forcing an omnipotent being onto a conference call it follows that omnipotent beings will never do conference calls, even if there was a reason for them to do so, which there isn’t.

This led Büchstein to a dark place. Rather than simply rebutting Descartes’ assertion that there must be a God, by illustrating one was not necessary, Büchstein went further: “a universe in which conference calls necessarily exist,” he contended, “is logically inconsistent with the continued presence of an omniscient, benign, omnipotent deity”. He took this as an a priori proof of the non-existence of God.

There is no new paradox under the sun

As he fell deeper into his Dengue-inflected hallucinations, Büchstein went the other way, skirting dangerously close to a sort of modernist nihilism. “If determinism is true,” he reasoned, “then everything is already known, or may be extrapolated from what is already known and is therefore, is constructively known. Ergo, as all forthcoming deliberated outcomes can therefore be deduced without having to go through the pain of actually deliberating about them, and as a conference call is of its essence a “deliberating thing” — a res deliberans[1] — a conference call has no ontologically essential purpose and can be dispensed with.”

This was, for a while, a moment of great joy, notwithstanding he had contradicted himself within the confines of a single, somewhat laboured, sentence.

But this contradiction, of course betrays a paradox, because the original logical inference generated by the theory of the conference calls is different if the call is not actually held. That is, the information content of a conference call is path-dependent. If the conference call happens, it has one value. If the it does not, it has another value. This is a sort of Schrödinger’s cat sort of affair. Büchstein dubbed this the “substrate-ambivalence” of the conference call. It remained a genuine mystery in management theory until the impish German jurist Havvid Dilbert established that, whether you hold them or not, the informational value of a conference call for participants, observers, and indeed that sainted remainder of the outside world who remain quite oblivious to them, is identical: that is to say, zero.

Thus, Büchstein’s paradox melted away with his sanity in that Mandalayan asylum, only to be replaced by a more intractable conundrum which Dilbert had not solved at his untimely passing, and remains with us to this day: why are there conference calls at all?

In popular culture

Buchstein’s theosophical musings, wanting as they were, found expression in the developed drafts of his final, unfinished play, Die Schweizer Heulsuse.

Triago: Good colleagues: there are but twenty minutes left.

Wouldst you thy precious time reclaim;

Or may we keep afoot our infinite game —

With more, or any other, business? Search anew,

What items canst be tabled without ado?Gloucester: Nothing sire.

Kent: Nor from I.

A period of silence around the table.

Queen: (Aside) That irksome twerp.

A world of richness awaits this piffling parley.Triago: How say you, brave Herculio?

What agenda fodder doth the gods portend?Herculio: The gods? The gods? Methinks you jest.

Th’almighty has no use for paltry conference.Triago: I think he does, sirrah!

Queen: Oh, ho! How so?

What matters lie upon thy parchèd record

That be yet unbeknownst to sacred mind?

Whose cogs and toothèd gears

Whose immaculate escapements

All history — gone and yet to come — defined?

What need hath she, or he

Who bid the lion lay with lamb

For this dismal convention?Nuncle: Thou maketh me to meet —

Therefore I am.Triago: How should I know, my Queen?

How should I know?Queen: Quite so, good sir, quite so. I must away.

Maketh thou the time-ball drop.Exit Queen

Herculio: With all my heart, my Liege —

One has to hop.Exeunt[2]