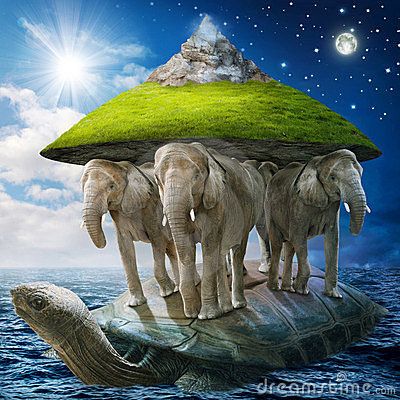

Elephants and turtles

|

Philosophy

|

A Hindu cosmological myth, in which the world is borne upon the back of four elephants who in turn stand on the world turtle, Akupāra (Sanskrit: अकूपार), which has a pretty obvious logical flaw that atheists like to think neatly demolishes the intellectual pretensions of organised religion — which it does — while not noticing how neatly it also demolishes the intellectual pretensions of secularists, lawyers, scientists and, well, atheists at the same time. For what — or who — is Akupāra standing on? There is of course an infinite regression here. Had Douglas Hofstadter been a hindu cosmologist he might have placed the lowermost turtle at sufficiently remove back on Earth. A strange loop. Anyway he wasn’t, and they didn’t so we’ll all just have to ponder the opportunity missed.

Note, though, that pace the atheists, this is not a problem with religion, but with epistemology. Every truth depends on a previous one. There is no bedrock truth; they loop around: Every good dictionary is circular. A non-circular dictionary is complete. Indeed, if you take Douglas Hofstadter at his word, that very circularity — reflexivity — is the special sauce of language.

So, like all good metaphors, the Hindu creation myth works best if you don’t interrogate it too closely. It begins to run out of explanatory force. Once you start poking around ibn the basement, with all the turtles, you see things you can’t unsee. Hence, successful religions have all kinds of mind tricks and guilt trips to stop punters rooting around in the basement.

But all good creation myths have in common a profound commitment to truth. It’s in their constitution: their very purpose is to stop folks bickering and encourage them to get along, by means of a uniform, universal, comprehensive code of things: There is a truth about the universe, and it goes like so. So all the major religions have commandments, pillars, principles of behaviour and thought.

To make a whopping great narrative, try this: the enlightenment slowly suffocated God: it fell to Charles Darwin to deliver the coup de grace and Friedrich Nietzsche to announce it to the world — some parts of the world still haven’t quite caught up — and this yielded the crisis of modernity.

Now, “God” is a Big Idea — it answers a lot of questions and gives a lot of guidance about how to behave, and how to organise, and over four millennia generated plenty of auxiliary hypotheses to adapt to the species’ changing circumstances, so when we killed God, we gave quite a lot else away. A means of telling right from wrong, and true from false, for example. The enlightened western intellectual tradition tradition needed to reinvent all these organising principles from scratch: to ditch one Big Idea, you need to replace it with another. For otherwise — nihilism, right?

Now, here is an interesting thing: what if the very idea that there must be a Big Idea, at all, derives from the very Big Idea that now lay lifeless on Charles Darwin’s specimen table? Hold that thought, for the Big Ideas that rushed in to replace it all cleaved strongly to the notion that there must be a Big Idea. The enlightenment was, in a profound way, utterly bound to the intellectual mores from which These attempts to do so, from the rational precepts of enlightenment: the scientific method, we call modernism.

In any case, failure of the “world turtle” metaphor is in its own inadvertent way, a potent symbol for the malaise of our time. A meta-metaphor. Knowledge, friends: we are getting rather close to the turtle.