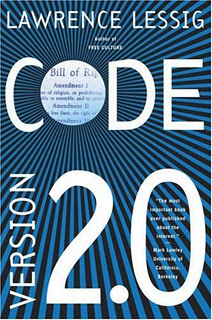

Code: Version 2.0

|

Code: Version 2.0 — Lawrence Lessig

Extraordinary book: essential modern philosophy

If you take Web 2.0 at all seriously then, whatever your political or philosophical persuasion, Lawrence Lessig’s Code: Version 2.0 is a compulsory read.

This is a novel and striking re-evaluation of some fundamental social, legal and ethical conceptions. It is persuasive that our traditional, deeply-held, and politically-entrenched ways of looking at the world are not fit for purpose any more.

Intellectually, this is therefore an extraordinary, eye-opening, paradigm-shifting, challenging, exhilarating read. Some say it is a book for lawyers: I’m a lawyer, so maybe that’s me, but this is no ordinary legal text. It should be of interest to all who have a political, philosophical or scientific bone in their body.

Lessig charts the technical and epistemological grounds for thinking that the internet revolution (and specifically the “Web 2.0” revolution) is as significant as any societal shift in human history. Generally, this is not news for people in the IT industry, who deal with its implications day-to-day, but for our legal brethren, who tend of be of a conservative (if not technophobic) stripe, this ought to be as revelatory (and revolutionary) as Wat Tyler’s march on London. Now we have a hyperlinked, editable digital commons, the assumptions with which we have constructed our society need to be rethunk.

For example, copyright: a law framed in the pre-digital era where there was no ready means to replicate “content” which didn’t itself involve considerable labour and expense, it made sense to protect intellectual property in this way. But faced with the new commercial imperatives of the digital age, Lessig argues compellingly that the existing legal framework simply cannot apply, that any attempt to fit it to the new social reality which, Q.E.D., must have been beyond the contemplation of the framers of the law is a creative (and therefore potentially illegitimate) legal/political act. Down this path, Lessig’s arguments have more interest for constitutional lawyers and may lead the lay reader a little cold.

Lessig provides us with an alternative framework for discussing legal issues like copyright, intellectual property protection and privacy, and is convincing that our old tools for conversing on these issues — which predate the digital revolution in its entirely, let alone the internet revolution or Web 2.0 — just won’t give us useful answers to our conundrums. Lessig also re-opens the book on what even counts as law — what we mean by “regulability” — in an environment online where the power exists, by computer code, to create “laws” of a more natural kind — that are laws not because they *should* or *may* not be broken, but because they *cannot* be broken.

Lessig’s startling conclusion is, therefore, to reject entirely the Utopian wish, frequently expressed by citizens of the net, that traditional legal controls are dead and that Web 2.0 vouchsafes to us an eternal state of libertarian bliss — but to assert that, quite to the contrary, Web 2.0 is, to use his own ugly expression, “architected” to allow maximum conceivable regulation, and that activities online are capable of a total regulation that, offline, would never have been feasible. Lessig warns therefore that we stand (or at any rate approach) important political crossroads where the public decisions we make as a community about how we allow internet architecture to develop will have a huge bearing on the development of cyberspace — and therefore our rights and personhood in cyberspace — for the hereafter.

Among the fascinating ideas here, which have application way beyond the legal and digital realms, is the “end-to-end principle”, by which the internet is (ugh) architected, which says that for a distributed system to be maximally effective there should be the minimum complexity in the basic network necessary to provide common structure to all users so that they can use the information as flexibly as they want: the complexity should therefore be at the edges of the system and in the hands of the user. Thus the core wiring of the internet is a rudimentary router of tiny packets of data which are then assembled by the end-user (in a browser or other application). But the same principle applies to physical transport networks (a road system has less intrinsic complexity than a rail system, for example: the complexity on a road network is pushed to the edge and manifests itself in the vehicles we drive: on a rail network, by contrast, the train is part of the network), and indeed political and social networks (a liberal political regime has less intrinsic complexity than an interventionist one — the complexity is pushed to the edges of the network and users build that amongst themselves).

I thought this was a profound insight, and perhaps has implications beyond the scope of Lessig’s thesis, and if properly considered have the effect of mitigating some of the alarm he feels.

Just as he rightly brings the Utopians to book for believing their hype about this golden new age of freedom — of course, governments and vested interests will figure out the net and how to effectively regulate it, like they have every other social revolution since Wat Tyler’s time — I think his own vision is needlessly dystopian. It assumes that code will be able, at some point, to regularly, systematically, reliably and effortlessly know every single fact about every one of us — and hence we are ultimately regulable.

But this isn’t realistic. Just as it would be impossible to accurately predict the trajectory of the proverbial crisp packet blowing across St Mark’s Square, no matter how sophisticated your equipment and scientific knowledge, the web is too weird, too non-linear, and people’s applications for it too dynamic and unpredictable and the “true meaning” of our communications too innately susceptible of multiple interpretations for any code to ever fully get the better of us (nor even, really, close).

For example, I once spent months, with considerable IT infrastructural support, trying to figure how to reliably capture simple, non-controversial attributes of regular documents which routinely and predictably pass between an easily identified and small community of users across a tightly defined and fully monitored part of an internal computer system — and it proved to be quite impossible. The idea that one might reliably capture deliberately masked communications even from this minute sample seems absurd, and the idea that one could do this across the whole worldwide web preposterous.

Just as the spammers and virus programmers keep ahead of the filters, our freedom is adaptable and valuable enough to keep ahead of The Man.

Well, that’s the hope, anyway. But in the meantime, this book is certainly food for thought.