Molesworth self-adjusting thank-you letter

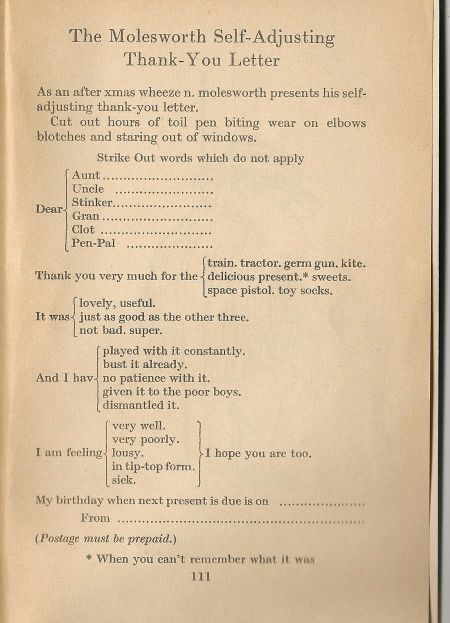

When a thought leader predicted[1] that document assembly would lay waste to the legal profession a few years ago, he can not have known how late to the party he was. For the forefather to this vision was the noble, fearless and brave nigel molesworth (cheers cheers), the curse of st. custards and, of course, one of the young (and, frankly, old) JC’s great heroes. The Haifa Scrolls of document assembly, from 1954,[2] is set out at the right.

|

Modern applications

And here, in the new world, we find wondrous new applications. We even have a law firm, those collective sparrows of finance, Simmons + Simmons, who stumbled upon the idea but executed it so un-nimbly that, far from solving the problem of negotiating tedious contracts, they made it worse.[3] Still: the murmuration’s loss is the JC’s gain, and what’s mine is yours, readers, so let the legal starlings for ever be Freddie Wallace to our Chuck Darwin.

Here’s the idea — free to you, but give the JC a knowing wink in your acceptance speech, okay?

Take a common, but unstandardised, contract — ideally one that legal eagles are in the habit of sending each other but which addresses a risk proposition that can, and really ought to, go without saying. In Simmons’ case, it is the terms of business; but let us take that iatrogenic staple, the confidentiality agreement.

Let’s say you are about to embark on a “project” with your client. The project is a simple, workaday thing; its purpose, though easily articulated, carries an appreciable, but containable, risk of harm — mainly embarrassment, if we are honest[4] — should you not treat the information your client sends you with suitable care.

Your client’s legal department, thus, sends you a confidentiality agreement. The evolution of legal technology being what it is, you would expect this to be a standard, short, utilitarian communiqué, rather like a telex: it will succinctly address the four or five points an NDA must, and you can nod it through on a cursory glance, and thereafter you and your counterpart’s legal departments can be on your respective ways, allowing the business folk to get on with whatever unseemly business people of commerce do, in these straitened times.

It won’t be anything of the kind, of course: it will be a fantastical, paranoid, weaponising tract. It will comprise fifteen pages of closely-typed 10 point text, by which your client will purport to commit you to all kinds of exclusivities, indemnities, and open-ended covenants to mount legal defences to see off polite requests for regulators and the like.

This will oblige your legal eagle to engage in close combat with theirs.[5] You will have to sift through the text looking for buried innuendoes. You will mark it up and send it back, and settle in for a 2 two week pitched battle where you and your client’s legal shell each other with increasingly improbable hypotheticals justifying the stances you want, respectively, to sustain or resist, before your business people can get busy with it.

This helps no-one, of course, although it may help quell the inner road-rage that motivates those who seek out arguments for a living.[6]

Now for many years this was a fine state of affairs, although it does tend to make sales people —exitable at the best of times — a bit jumpy. But alas, this scandalous inefficiency finally attracted the attention of the middle management layer. Middle managers know little of any value about anything, as we know — that is why they are middle managers — but the merits of a humble confidentiality agreement are basic enough for even a simpleton to grasp, and the NDA has become something of a bête noire, or a cause célèbre, depending on how you look at it, for the chief operating office. In the NDA it apprehends something it can fix.

Being modern, thought-leader types they see a blindingly obvious way of doing this: reg tech. Now you and I might think, differently: if the negotiation process was a Rube Goldberg machine already, then engaging machine learning and natural language processing to intermediate is hardly going to help. But there we have it. No-one asked us.

So I’m asking us. And answering.

The JC’s self-adjusting confi agreement thank-you letter

But if we were to think of this from another perspective, we can get to a simpler answer. Start with modern theology. Apply the words of serenity’s prayer, and find the wisdom to know what you can change, what you cannot, and go from there.

What we cannot change

We know we cannot stop legal eagles in our clients’ employ sending outrageous legal terms. That is their prerogative. You would sooner stop the tide washing over your throne, or nail jelly to the ceiling. What we can instead do is accept it, as it is, without amendment (barring adding your name and address). This will make their legal team happy — though is that a tremor I detect in your own trousers, counselor? Fear not: there is a “but” coming up.[7]

Sign it, and send it back. With a little note attached.

What we can change

We accept it as is, only with a “but”. This but is the following:

As you can imagine, we review a lot of forms of confidentiality agreements. To progress with this business opportunities as quickly as possible, we have taken a commercial decision to accept your form as you have submitted it, as long as you agree to the following overriding principles, which will prevail where they don’t match what is set out in the form of agreement:

- We agree to keep confidential the non-public information you give us relating to the project. That is the scope of this agreement. It does not apply to any other information.

- We are not seeking any exclusivity, asking you to restrict your activities with any other party, or asking you to assume any other legal obligations, and nor are we assuming any obligations to you other than those directly connected with the care of your confidential information.

- We accept legal and equitable remedies for ordinary breach of contract. We will not be otherwise liable to you: no indemnities, no guarantees.

- At your request, we will (at our option) return, destroy or put beyond practicable use your confidential information.

- We may only share confidential information you give us within our organisation on a need-to-know basis, but may share it with our professional advisers, on whom we will impose an equivalent duty of confidentiality.

- We may disclose information to regulators where it is reasonable to do so, but we will disclose no more than that. We do not have to tell you where we make such a regulatory disclosure.

- [The agreement will terminate two years from the day we sign it, being today.[8]]

This won’t work...

Legal eagles will of course recognise this as not an acceptance at all, but a counter-offer. This being the most elementary aspect of contract law, it will not be lost on your client’s legal department either. Nor should it be: it is not meant to be a trick. It is a counter offer.

Why does this advance anything? Well, like so: it shifts debate from your client’s laborious tract to your brief one. You have stated your position succinctly. Your client can, on its own dime, work if your proposal is fair (it is, by the way). This aligns interests correctly: since they have elected to serve up a Biblical agreement; they can trawl through the damn thing, if they must, ensuring your headline counterthrust doesn’t undermine their vital protections (it doesn’t). But in any case, if they wish to re-impose their most precious points they must extract those out of their nonsense omnibus, and put them on your half-page. And there, you can see it, and quickly decide whether to agree it or not.

In any case it obliges your client to bring to your attention any non-standard points it wishes to hold you to, rather than expecting you to find them in its byzantine peroration. In any case the worst outcome is that you have moved the theatre of conflict from a sprawling tract of impenetrable verbosity to a half-page of bullet points. But there will be many clients who will just agree it. After all, what you have done, in simple terms, is stated the basic principles of a fair confidentiality agreement.

See also

References

- ↑ Darryl R. Mountain, Disrupting Conventional Law Firm Business Models using Document Assembly, International Journal of Law and Information Technology, Volume 15 (2007)

- ↑ The same year as the Fender Stratocaster. A signal year, to be sure.

- ↑ See the Simmons TOBs offensive

- ↑ The notion that much of what passes between the legal departments of modern financial institutions is clever, much less proprietary or sensitive, is one of the great canards of our age.

- ↑ This is known in the trade as a “dog-fight”.

- ↑ You, my young eaglet, are just such a person, so do not scoff.

- ↑ “Everything before the word “but” is horseshit”. — Game of Thrones.

- ↑ Some people insist on a term for a confidentiality arrangement. I have never understood why.