Stakeholder capitalism

Once upon a time, not terribly long ago, the shareholder was an opaque yet sacred being, somewhat divine, to whose improving ends everyone engaged in the company’s operation twitched their every fibre.

|

This will to shareholder return sprang from the brow of Adam Smith and his invisible hand:

“...Though the sole end which they propose from the labours of all the thousands whom they employ, be the gratification of their own vain and insatiable desires, they divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements...They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species”[1]

This is, by the way, a breathtaking insight; no less dangerous or revolutionary than Charles Darwin’s: from collected, unfettered, selfish actions emerges optimised community welfare.

The modern corporation is, philosophically, the embodiment of that idea. Look after the shareholders, and society will look after itself.

By pursuing only its shareholders’ enrichment the corporation, so the theory had it, was more nimble, more responsive to society’s demands, and able to magically allocate capital wherever the community most needed it at any time. “Compare this,” declared gleeful proselytes, “with the disasters of central planning, five-year plans, great leaps forward and so on.”

Shareholder capitalism had its advantages, to be sure: not least of which was easy performance measurement: one could evaluate every impulse, every decision, every project, every transaction against a single yardstick: was this in the shareholders’ best interest?

Shareholders’ interest, in turn, could be measured along a single dimension, too: profit. Nothing else mattered. The professional-managerial class, and their endemic agency problem, were hemmed in: you can’t hide from after-tax profit.

That was then. The narrative has changed to fit our millennial world. Unalloyed selfishness has become, to the modern conscience, intolerable. As long ago as 2003, Joel Bakan put the argument[2] that a legal person whose sole motive is the short-term enrichment of its investors has the clinical characteristics of a psychopath. Things have only got worse for Adam Smith’s conviction in the emergent goodness of shareholder profit.

We are cancelling and redrawing the world: let us cancel and redraw our corporate aspirations too. Shareholder capitalism is, by design, venal, selfish and riven with bias. Its unseemly stampede for profit demonstrates an abject want of care for unseen victims.

And so it has come to pass: “stakeholder capitalism” has displaced shareholder capitalism. Gordon Gekko is out. Arif Naqvi is in.[3] We, the planet, ask corporations to orient themselves toward all their “stakeholders” — customers, creditors, suppliers, employees, the community, the environment, the marginalised multitude that suffers invisibly under the awful externalities of industry and — last, but not least! — shareholders. Corporations must not profit at the expense of the wider world.

This view seems so modern, so compassionate and so right — so fit for Twitter — that it is hard to see how anyone can ever have thought otherwise. Yet they did, consistently, from the publication of Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments down the centuries, through the titans of American commerce, Chicago economics and Hollywood villainy.

However intuitive this new approach seems, it is still a striking reversal. It has passed with barely a shot fired. Even that trade union for unreconciled boomer gammons, the Business Roundtable has joined in: last year, it “redefined the purpose of a corporation” away from the outright pursuit of profit towards promoting an economy that serves all Americans. “It affirms the essential role corporations can play in improving our society,” said Alex Gorsky,[4] Chairman and CEO of Johnson & Johnson and Chair of the Roundtable’s Corporate Governance Committee,[5] “when CEOs are truly committed to meeting the needs of all stakeholders.”

We are not sure who asked the Business Roundtable, but in any case we find ourselves taking a different view.

This not an “awokening” so much as a collective concussion of the sort occasioned by a stout blow on the head. These people are either outrageously talking their own book, or we have all gone mad.

Skeptics of the mass-delusion conspiracy theories can relax: it is almost certainly the former. For stakeholder capitalism codifies the agency problem. It diffuses the executive’s accountability for anything the corporation does, putting the professional-managerial class beyond the reproach of the one constituent stakeholder group with the necessary means, justification and consensus to call it out: their shareholders.

Stakeholder capitalism, folks, is a swizz.

Under Joel Bakan’s theory, remember, it is not the shareholders who are psychopaths,[6] but the corporation as a distinct legal person itself. The shareholders are only motivation for its pathology.

But in a well-balanced polity, shareholders will come from all walks of life. The pervasiveness of pension funds in the equity markets means that, as far as makes any difference, they do.

Shareholders are diverse in every conceivable dimension, bar one: they can be young or old; rich or poor; left-leaning or right; tall or short; male or female; gay or straight; black or white or, in each case, any gradation in between. They don’t have to know each other, like each other or care less about each other. On any other topic, their aspirations and priorities will jar, clatter and conflict. If you put them in a room to discuss anything but their shareholding, you would not be surprised if a fight were to break out.

Still, on that one subject, they are totally, magically, necessarily aligned: each will say, “whatever else I care about in my life, members of the board, know this: I expect you to maximise my return.”

About that “return”

Now you might argue that, since we are all shareholders in one way or another, stakeholder capitalism is really no more than “paying attention to shareholders’ wider interests, not just their pecuniary ones.” This way, polar bears get a look in if and only if their welfare is in the shareholders’ wider interest.

But that isn’t stakeholder capitalism: that’s just a stupider version of shareholder capitalism. It simply replaces shareholders’ monetary interests for their moral ones. That is stupid because it displaces the shareholders’ moral judgment with the CEO’s.

That is not the deal, readers. The CEO is the shareholders’ servant. The CEO doesn’t get to moralise on their dime. And anyway — see below — if you had the pick the last bunch of humans on Earth to whom you would delegate the exercise of your personal moral imperative, it would surely be the professional-managerial class.

Besides, to substitute the shareholders’ wider interests for their narrow financial one is to miss the single clinching insight. As long as it is all about return, there can be no arguments.

The abstraction of value

How one values a bushel of sorghum depends on one’s circumstances, needs and predilections. Some may value it highly, others not at all. Its value, even at a single moment in time, is relative. Value was locked into the physical commodity. What you didn’t want you could sell, but with significant frictional costs. Long ago, our forebears[7] invented a way to distil pure, abstract, immaterial value from the relativising commodities or perishable substrates in which it is usually embedded:[8] they called that abstracted value “money”. Cash does not go off, cannot be eaten, and does not depend for its value on anything else.[9] Cash is abstract value.

Hence its value as a yardstick for corporate performance. In discharging their sacred duty, those stewarding the affairs of corporation could not have clearer instructions: should the return they generate, valued in folding green stuff, not pass muster, there will be no excuses.

There is no dog who can eat a chief executive’s homework, no looking on the bright side because employee engagement numbers are up, no consolation to be taken in the popularity of the company’s float in the May Day parade: if the annual return disappoints, members of the executive board, expect to get shot.

Now moral imperatives can certainly be part of that calculation, but only as a second-order derivative: it may be that virtue-signalling about the environment or putting a float into the May Day parade is a good marketing tactic and generates greater revenues: if so, fill your boots. But you must still measure its success by that single monetary measure.

Shareholder return is, in this way, not a device to systematically gouge the environment on behalf of an anonymous capitalist class. It is a device to stop executives systematically gouging the people whose investments they are managing.

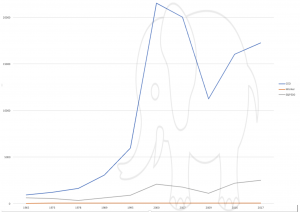

Now, before you cry, “but surely, shareholders need no protection from chief executive officers! It is the disenfranchised underclass at the margins of society who must be protected!” consider the chart to the right, taken from data published by the Economic Policy Institute in 2018,[10] which maps CEO compensation against worker compensation and the performance of the S&P500 since 1965.

It gives a pretty good picture of how shareholders, workers and executives are doing relative to each other. It’s hard to see, but the line hugging the x axis is worker compensation, and it has improved, at an annualised rate of 2.5%. Those rapacious shareholders gained at 8.5% per annum. But “Chief Executiving” is the line of work to be in, folks: not even counting the heady days of 2000, the overall return since 1965 shows a growth rate of thirty five percent per annum.

So before we cast the poor shareholders’ interests to the wind, ask this: by switching to stakeholder capitalism, who benefits?

Stakeholder capitalism means never having to say you’re sorry

When shareholders hold the whip hand, an executive’s goal is simple. Make money. That clarity of purpose evaporates the moment that remit expands. Multiple stakeholders means multiple interests, which must conflict. How do you arbitrate between creditors and the local community? Between the environment and customers? Between penguins and polar bears?

That is before the key question even presents itself: who are these stakeholders of whose wellbeing I am suddenly guardian? There is no ranked list. Unlike shareholders, whose names and stakes are set out on a register, the constituents, interest groups, factions, priorities, narratives and moral imperatives of “the world at large” are utterly indeterminate.[11]

How do you even know what your stakeholders’ interests — beyond having as much of your soda pop as you can make, as cheap as you can sell it — are?[12]

Whose interests have priority? Why? Now a failure to generate a decent cash return can be blamed on — well, anything — your success in reducing the number of smokers in the accounts department, or your community outreach team spent all your excess cash on beautifying a local park, or you chose a buildings manager who was twice the going rate but had a better anti-modern slavery policy.

Stakeholder capitalism means the executive class always has an excuse. Always. For everything. To run a company for the world at large is to run it for no-one. And when a professional-managerial class of agents can’t work out who else’s interests to put first, what do we expect them to do?

Rhetorical question.

Are corporations best-placed to look after everyone else’s interests?

Yes, customers are your stakeholders, and they have an interest how you conduct your business, but — at least in a healthy marketplace — they have a means of controlling that a lot more direct, regular and effective than do shareholders: they can buy something else. You can only maximise shareholder return by persuading lots of customers to buy your stuff.

By contrast, shareholders are a bit like voters in a representative democracy: their main weapon is the power of sale; beyond that, there’s the AGM, and unless you’re an institutional money manager, don’t expect anyone in the C suite to be massively bothered how you vote.

Employees — especially those in the executive suite — have all the power they need to influence the company. They are there, every day, making every decision.

Of course the disenfranchised minorities at the margins of our community need a voice. As we argue elsewhere, an optimal society is pluralistic, tolerant, defends those at the margins and, all other things being equal, prefers their interests when they conflict with the majority that is perfectly able to look after itself.

The question before us is not whether to protect their interests, but how. There are plenty of better ways: representative democracy, for a start.

But even so, shareholders are not monolithic investing homunculi: they are ordinary people with disposable income. If they want to beautify the inner city, save polar bears or fight water scarcity, they can do that directly. That is a far better way to allocate capital. It puts control in the investors’ hands, where it should be. Investors do not need to channel their charitable activity through the medium of their equity portfolio.

We cannot fathom the moral agenda — if there is one[13] — behind an investor’s decision to invest in a bank stock. Who knows if they care about water scarcity, or polar bears? But if the alternatives are “assume they are basically after a capital return” or “let the chief executive decide what the moral priorities of her shareholders are”, then it is not a difficult choice.

A bank should prioritise prudent lending standards and timely risk management. It should stick to its knitting. Governments, NGOs, supra-nationals and dedicated charities with resources, expertise and focus can deal with water scarcity. If bank shareholders want to address water scarcity, they can give their disposable resources to water scarcity specialists. That is surely more effective than buying bank stocks.

About those executives

The proposition that a disembodied pile of papers is intrinsically psychopathic is a bit far-fetched. The proposition that the collected shareholders of all listed companies in the world are all psychopaths is even more far fetched. The idea that, against the average, those who make it to the top of the greasy corporate pole have an element of the sociopath to their personalities? That’s not far-fetched at all.

See also

References

- ↑ The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) Part IV, Chapter 1.

- ↑ The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power It is a fun book, but it is nutty.

- ↑ Until his arrest.

- ↑ No relation to that Mr. Gorsky, as far as we know.

- ↑ Now I don’t want to intrude here, but is being Chairman and CEO really the best example for the chair of a corporate governance committee to set? Here is the Harvard Business Review on the subject.

- ↑ Shareholders who themselves are corporations probably count as psychopaths, come to think of it, but the point remains valid. Shareholders are not necessarily corporates, and at some point all shareholdings must (right? Right?) resolve back to some living, breathing individual.

- ↑ No, not enlightened, white, male, cis-gendered, colonial oppressors: ancient Mesopotamians.

- ↑ Granted, it is imperfect: until recently much cash did have a substrate (paper send coins), and its value is still coloured by the credit consensus of its issuing central bank, which can control its supply and demand, but the substrate issues are largely resolved, and consensus in the bona fides of the Federal Reserve, ECB and Bank of England has proven a lot more robust than that of whatever anonymous collective coded the crypto currency do jour. Don’t @ me, Satoshi freaks.

- ↑ Okay, okay, other than “the full faith and credit of the issuing central bank”, in whom everyone in the market had a common interest. See previous footnote.

- ↑ https://www.epi.org/publication/ceo-compensation-2018/

- ↑ Those railing at this idea are invited to familiarise themselves with the works of Kant, Mill, Hobbes, Hume, Smith, Nietzsche, Nozick, Wollstonecraft, Warnock, Butler, Rawls, hooks and Marx and return with a concise summary.

- ↑ There is a hand-wavy argument that executives should have in mind the “best interests of the community” and not anyone’s selfish needs and wants. But who knows what that is? How does a moral agenda determined by the corporate executive class — mainly white, ageing, cis-gendered, post colonial men, in case it at slipped anyone’s attention — improve on no moral agenda at all?

- ↑ And honestly, is there likely to be a moral dimension to investing in a bank stock?