The curious structure of an MTN

|

The Law and Lore of Repackaging

“bond” as explained to my neighbor Phil

Financial concepts my neighbour Phil was asking about when I borrowed his mower. Index: Click ᐅ to expand:

|

You will know old Grandpa Contrarian’s story of the farmer and the sheep. It is illustrated richly in every cove, inlet and waterway of the financial markets, but is no better exemplified than in the genetic structure of a medium term note programme.

These, for the fortunately uninitiated, are architectural structures by which corporations raise funds in the international debt capital markets. Their history is long and mildly diverting at best — the type who naturally deals in debt instruments is not really given to intrigue — but for our purposes it is important.

Conceptual underpinnings

Now: as per the panel summary, a bond of any kind is an IOU, in that it represents an entitlement to be repaid a loan. In earlier epochs one would borrow against a “note” — literally, a signed piece of paper indicating your preparedness to pay a sum to whoever presented it, in exchange for its surrender.

The neat thing about this kind of note is its transferability: the original lender can “negotiate” it — sell it[1] without the issuer’s permission, or even knowledge — and its value will be the present value of the issuer’s promise to pay. A note is a unilateral contract, therefore. A conventional loan is a bilateral contract, and the job of transferring ones rights and liabilities under it is more involved, and often requires the cooperation of the borrower.

The other neat thing about notes compared to loans is that you can easily divide a big borrowing into lots of little notes, rather than a single big one. Thus, you can access a wider pool of lenders — including Belgian dentists, as we will see — each of whom can manage its own exposure without reference to the others, by buying or selling bonds in the secondary market.

Notes therefore are more liquid, transferable things, and while they are outstanding the issuer need not even know who its creditors are: they hove into view only upon payment of principal or interest, when they would show up at the issuer’s office with their instrument in hand.

Industrialisation of debt securities

This all being the case, notes quickly became popular, and the process of issuing, selling and maintaining them industrialised. Notes were “security printed”, like banknotes. Interest payments were represented by perforated coupons that could be detached and presented (or “stripped” and separately traded): for a long-dated bond, where there wasn’t room for all the coupons, there would be “talons” attached entitling the bearer to a fresh strip of coupons. Issuers appointed banks as “paying agents” to handle the mechanics of dealing with holders, paying out on presentation and so on. In some jurisdictions[2] issuers needed to maintain a record of noteholders, so created “registered” notes which were profoundly different in legal concept — title transferred by entry in the register, whereas with a bearer instrument the security itself was the debt and title passed by delivery — and there needed to be terms to deal with certain unwanted contingencies: replacing lost or mutilated notes; provisions for noteholder meetings to consider amendments to terms and so on.

Now an IOU is a simple enough thing: the legal architecture making it all possible was another thing altogether: trust deeds, paying agency agreements, dealer agreements, prospectuses and so on, and the up-front cost of a “stand-alone” debt issuance was formidable. Thus emerged the medium term note programme — a pre-crafted architecture containing all the standard terms, appointments and so on, which an issuer could quickly “tap” when it needed to, in a fraction of the time and cost.

In parallel the information revolution arrived and notes started to trade electronically, in a clearing system[3]. Here noteholders’ interests were represented as electronic entries in their clearing system accounts there was no need for security printing, perforated coupons, a wide network of paying agents, and the identity for the time being of the holders was ascertainable, at least by the clearing system, which had to maintain the records on order to ensure everyone got paid. At the very heart there was still a physically printed note: just one: a “global note”, representing all the nominally issued notes, held by a “common depositary” — a custodian for the electronic clearing systems in which the notes are traded.

Residual DNA

By the 1990s, all notes, bonds and other securities were electronically cleared, and none has been security printed since. Nonetheless, the MTN terms and structure still bear traces of their physical biology, a bit like tailbones, appendixes and male nipples. The basic rationale is “well, the clearing systems might not work one day — you know, there could be some kind of post-apocalyptic, Mad Max-style future with everyone driving round in battle trucks and drinking their own urine — so I might need to change these into security-printed definitive notes, so we better leave these terms in just in case”.

Now the JC would be the last one to pooh-pooh the idea of a dystopian future — given the last few years he rather expects it at some stage, in fact — but, really: if you are eating caterpillars, presenting your coupons to the Luxembourg paying agent is going to be a long way down your list of priorities.

For reasons we can only put down to entropy, international bond terms and conditions are all shot through with laborious mechanical conditions that deal with how payments are made, where, by whom, on what conditions, to whom, should the notes be held outside a clearing system — a circumstance which, in the year of our Lord 2022, categorically will not happen — but which, thanks to the vagaries of historical appetite, meant might happen in a number of ways.

The logical structure of legal documents

Another thing we routinely forget is how important the logical structure of your writing is. Not just the organisation of the paragraphs, but the underlying semantic structure of the sentences themselves.

Any statement boils down to a logical proposition, and so on. It is just like software code, only instead of subroutines, conditions, logic gates, if/then statements lawyers call them obligations, rights, discretions, provisos, inclusos, options, definitions and so on.

For example, an obligation is an if-then statement; option is an either-or gate. Some legal operators like “(whether or not...)”, “(including without limitation...)”, “(for the avoidance of doubt...)”, “(may, but need not...)” do not constrain or expand the propositions they act on and can be omitted from a logic map (just as they should be omitted from the draft, dammit).

Any “logic gate” that splits a proposition into alternatives increases its inherent complicatedness. How you organise your gates, therefore, makes a big difference to how complicated your proposition turns out.

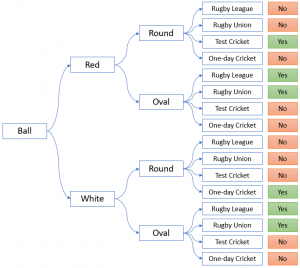

Take the alternative statements about cricket and rugby balls in the panel at right. (For non-initiates, rugby is played with a large oval ball which may be any colour; cricket with a small round ball which (for one-day cricket) must be white and (for test cricket) must be red. In the abstract, the variables at play here are:

- ball shape (round or oval)

- ball colour (red or white (or other))

- code (rugby or cricket)

- code variation, which in turn breaks into

- cricket: test or one-day (relevant only to cricket)

- rugby: union or league (relevant only to rugby)

How you arrange these variables can generate a more or less complicated logical structure, depending on how many distinct logic trees you create, and how you order the variables within a given logic tree.

One can (making it up as we go along) formulate a few design principles here:

Distinct logic trees

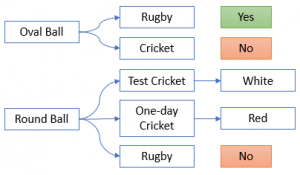

- Create distinct logic trees: The more distinct logic trees you have, the simpler your overall logic will be, though there is a limit (if each logic tree is a straight line then you don't have any logic at all).

- Make sure they are distinct: Distinct logic trees should not intersect with each other: their terms are mutually exclusive. (Intuitively, we suspect that the downstream logic beyond “cricket” will not intersect with any downstream logic beyond “rugby”).

- Avoid dead-ends: Try to minimise logic trees that end in a “no” as these are dead twigs that carry no legal/semantic content, but clutter up the structure.

Logic gates

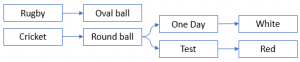

- Non-overlapping categories: Look for categories of items (such as “rugby” and “cricket”) that do not overlap and deal with them in separate logic trees. There is no real benefit to designing a single tree to accommodate these as alternatives.

- Postpone logic gates as far as possible: Where a logic gate must happen (that is, a split between sub-categories within a single logic tree), make it happen as late as possible, in order to...

- Avoid duplicating branches: Design each logic tree so that a given logic gate only happens once. (In the top diagram , the logic gate between the four code variations appear four times and the logic gate for ball shape appears twice, while the colour logic gate only once. If your draft is studded with expressions like “holder of a bearer note and/or registered owner of a registered note (as the case may, for the time being, be)” you have put your logic gate in the wrong place.

Definitions

Definitions can function as distinct mini-trees: On that note: a definition can act as a mini-logic tree if it contains a logic gate. For example, creating a definition like “Noteholder” means the holder of a bearer note and/or registered owner of a registered note (as the case may, for the time being, be) you can simplify the inherent logic of your text: the more the logic gate appears, the more economy a definition can bring.

Again, there is a tension: creating a definition that you only use once or twice can make comprehension harder. And sometimes by getting rid of the “duplicate gates” problem a definition obscured the fact that the logic was designed badly in the first place.

If you want to create a single proposition that covers all these variables, you commit yourself to a lot downstream branching, because that our single logical structure must accommodate all the permutations.

Therefore, if you frame your logic around first the colour of the ball then its shape, you buy yourself a number of branches which get to “NO” answers, and are therefore useless. See the first figure on the right. The colour of the ball doesn't matter for rugby, so you should postpone that branch until colour does matter for all the remaining branches. that is, after you have got to “cricket”.

The subject of the sentence and sequence of the branches makes a difference. For example, focussing on the ball first then its colour then its shape, and articulating these by reference to the games, commits to sixteen branches. If we break the proposition into two and focus first on shape, we can reduce this to five. if we reframe the proposition to focus on the game, we can get it down to the three, which is the minimum.

There is doubtless some information theory that optimises the logical structure, but intuitively it seems to us common options should be delayed as far as possible, and where games are largely common, separating out the points where they differ into a separate set of propositions may help.

See also

References

- ↑ Or pledge, or lend it.

- ↑ America being a prime example, thanks to the glorious strictures of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) of 1982, which introduced punitive tax treatment for bearer bonds, on the grounds that they were inherently fishy, income-sheltering things — a quality that never bothered the Belgian dental profession in the same way.

- ↑ In the European markets, there are two major clearing systems: Euroclear and Clearstream.