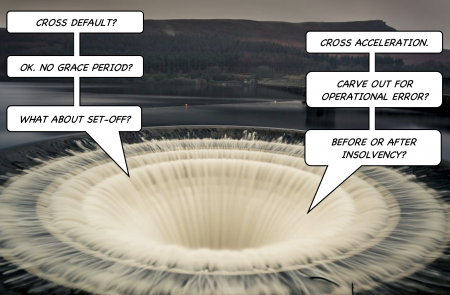

Negotiation oubliette

|

Negotiation Anatomy™

“All right, well what about cross acceleration? With a grace period? And a carve-out for operational error?”

|

A naturally-occurring subterranean cavern which forms when legal eagles gather to argue about trifles. Given enough nest-feathering, posturing and guano, even the most robust transaction will tend to fray and weaken and may in time collapse: those discussing suddenly find themselves in a dungeon on their own making, not knowing how they got there, but rather enjoying it all the same. While alarming for the commercial counterparties themselves, their negotiators will carry on, oblivious, sometimes for months or even years. [1]

Oubliettes are often prompted by the lawyer’s equivalent of the “clabby” conversation:[2] one struck up by an agent to appear busy while avoiding difficult work, wasting time and provoking maximum forward confusion.

Thus, they have a cosmological quality to them; like any black hole, they are impossible to see directly. We detect them only by their signature detritus: crushed aspirations of clarity and elegance, swirling around an event horizon of nothingness like so many gossamer dreams of greatness, gurgling around a galaxy-sized plughole. We enter these space-tedium singularities often, but always unwittingly, and it is only when scrabbling desperately for a way back out that we realise just what we have fallen into.

It is where you will go, taking the whole negotiation with you, the moment anyone proposes to accommodate any of the infinite count of tail events that in logical theory could but in recorded history never have come about. Seeing an oubliette coming early is vital, as is the right response, since falling into it is very easy to do. The notion of a “clabby conversation” translates very well into the world of contract negotiation.

Let’s say your credit department has it in its head that cross default is an important protection in a securities financing arrangement. This is a peculiar view, shared by few in the market and lacking a solid base in common sense, but of such gems of incongruous conviction propel many a livelihood in the Square Mile and we should not gainsay them. They are inexplicable brute facts of the universe, like the cosmological constant or the popularity of golf.

Your credit officer will say, “well, it won’t hurt to just ask” for a cross default, but just asking will prompt a discussion the parties needn’t otherwise have had, about the sorts of fantastic calamities that might come about in the possible universes that risk managers visit in their delirious dreams. The hypotheticals thrown into this debate will be as imaginative as they are tendentious: there will be a tangible air of prepostery emanating from either side’s submissions. But such is the path-dependency of negotiation: had no-one started this ball rolling, on a whim, none of imaginative perversity would have been given voice. Before you know it, the parties will be reciting the 14 stations of set-off. Perhaps they will canvass Someone will have the idea of importing some definitions from the ISDA Master Agreement, and from there all hope is lost. There is one way back, an infinite number of ways forward, into the abyss, and negotiators have no reverse gear.

It might jazz your risk colleagues, and it will doubtless appeal to your own Rube Goldbergian instinct — every transactional legal eagle has it, however deeply it will be buried, and it will overjoy your buyside counsel, and as you descend into the abyss, it will drive your clients up the wall.

See also

References

- ↑ An inter-affiliate stock lending agreement fell into an oubliette in Zurich in 2014 and none of the negotiators have been heard from since though, as far as anyone “on the outside” knows, discussions are still ongoing and progressing well.

- ↑ The Meaning of Liff: The Original Dictionary Of Things There Should Be Words For, by Douglas Adams and John Lloyd.