Payments waterfall

|

The Law and Lore of Repackaging

|

The priority of payments waterfall in a repackaging is an important, but fundamentally dull, piece of engineering, only made interesting, somewhat, when rating agencies intervene sometimes to make life harder for dealers. The idea is to sort out all the agents and their mandatory running costs first, then “senior” creditors — typically the broker as swap counterparty, though this is where rating agencies can intervene — then getting to the Noteholders and if anything is left after that, to the Issuing SPV.

Given the wide range of assets and structures that repackaging SPVs can engage in, the trick it to make it as general as possible. Legal eagles like to nest in the overhangs of a payments waterfall — they can make a frightful mess — so it pays to keep it as simple as possible.

The order of ceremonies tends to be as follows:

- Taxes: the SPV is set up to be tax neutral but given the wide range of instruments that can underly asset-backed notes, there could be some mandatory taxes: stamp duty, financial transaction taxes, VAT — that kind of thing. In any case the risk remains of changes in law and tax practice post issuance that would make unexpected taxes payable. If any are, they are paid first. Render unto The Man what is The Man’s, and all that.

- Trustee’s fees and expenses: The trustee tends to be “first among equals” of the programme counterparties. Like all the other agents, its ordinary fees for acting as trustee are paid upon issuance. This limb of the waterfall would only include extraordinary fees and expenses the trustee incurs when enforcing security or otherwise resolving the notes. Things like obtaining legal advice, making security registrations, filing discharges etc and taking action to defend any claims that might arise between creditors. These would be more significant were the security enforced – typically an early redemption is intended to happen without the need for that.

- Other programme agents: The remainder of the agents (other than Tramontana’s agency roles) are next. Again, unless there are extraordinary/unanticipated costs or additional work is required then there would be no further costs beyond those accounted for at issuance.

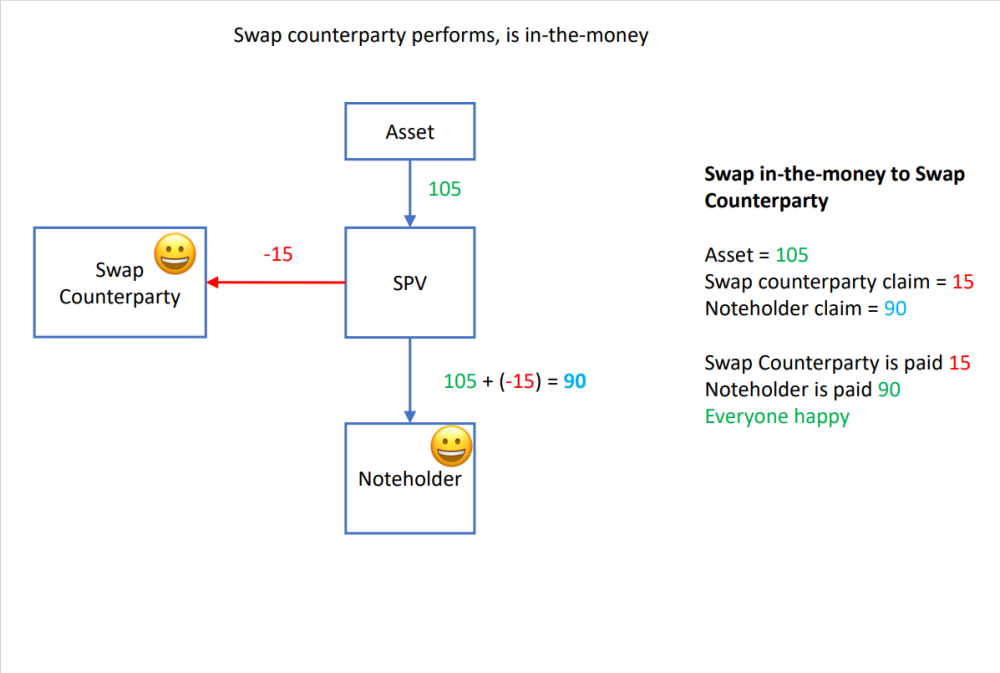

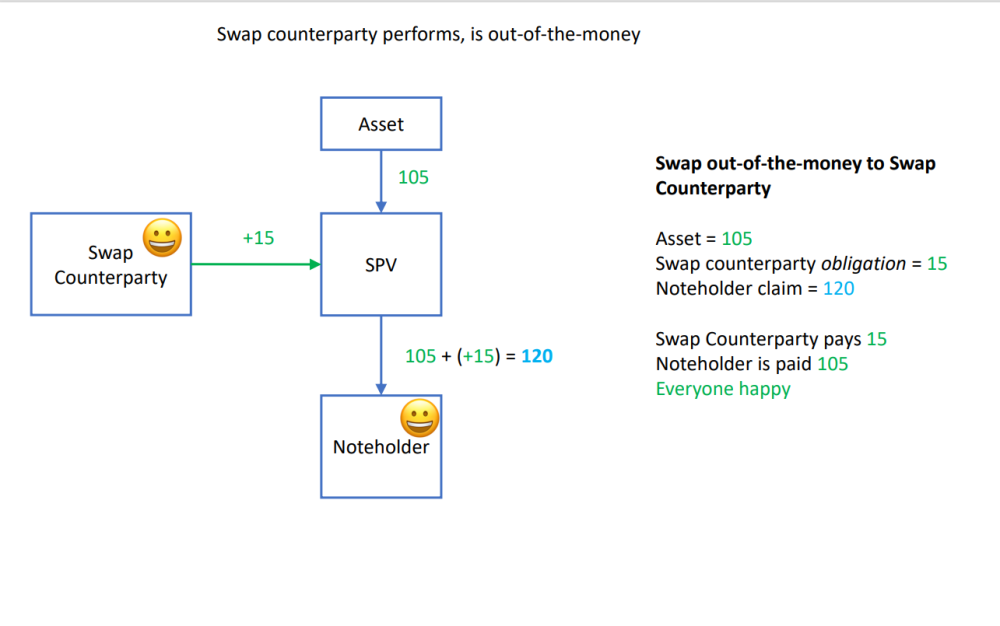

- Dealer/Swap Counterparty: if we take it as a given that the Note payoff is a par-asset swap of some kind (i.e., bond underlier ± swap mark-to-market) it makes sense that the swap should be closed out and its value settled before noteholders are paid.

- Redemption Amount/ Early Redemption Amount: this is the amount due to Noteholders under the Notes.

- Residual amounts: anything left — and for your common-or-garden repack there shouldn’t be anything left — goes to the issuer and is tossed into the pot and used for the Christmas party on Cayman Brac or something like that.

Rating agencies and the “flip clause”

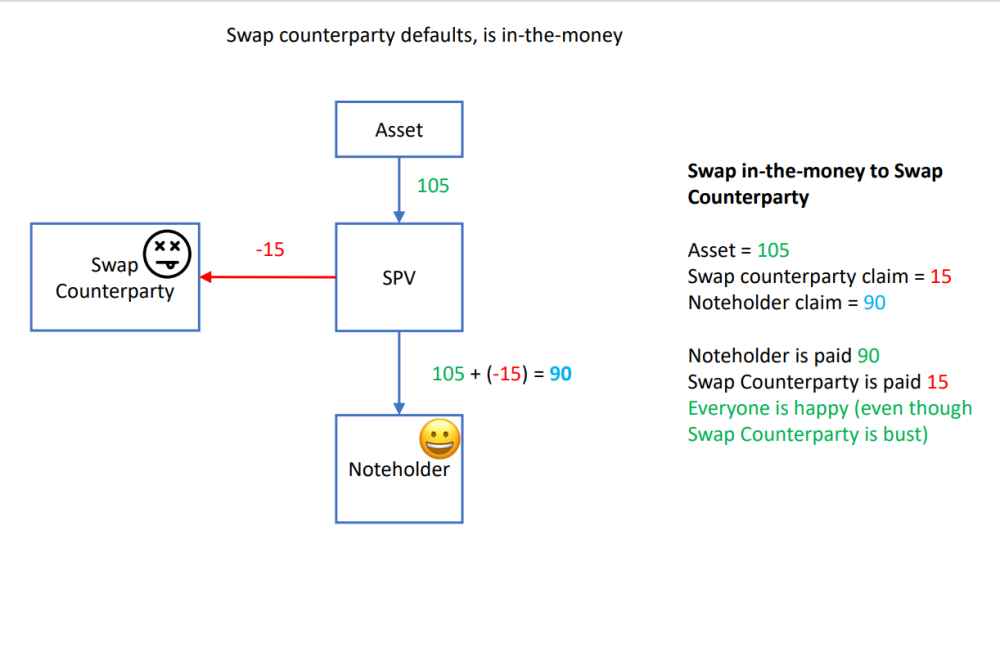

page=1 It became a la mode in the dog days of the CDO market for rating agencies to require the priority as between swap counterparty and noteholders to be inverted upon a swap counterparty insolvency — this is the so-called rating agency “flip” clause.

The theory was simple enough: if a swap counterparty has been gauche enough to default on its contractual obligation, even if forced to by the vicissitudes of insolvency — and realistically, that is the only time a regulated swap dealer of the kind that has truck with repackagings will default on its obligations — then it should forgo its privileged place in the security waterfall, and should slum it with, or below, the Noteholders.

At first blush this made sense, and seemed just, in a “living my own truth” kind of a way, but on second glance the analysis rather falls apart. Contractual arrangements are not meant to be punitive, judgmental or even evaluative: they are what they are, and you get what you bargained for regardless of the good or bad grace of your counterparty, as long as it is around and able to perform for you.

In the case, a Noteholder bargains for “the value of the underlying asset, plus or minus the value of the swap”. This is the basic articulation of the economic value of the Note. Thus, the value of the swap is necessarily cleared to zero in order to determine what the Noteholder is owed.

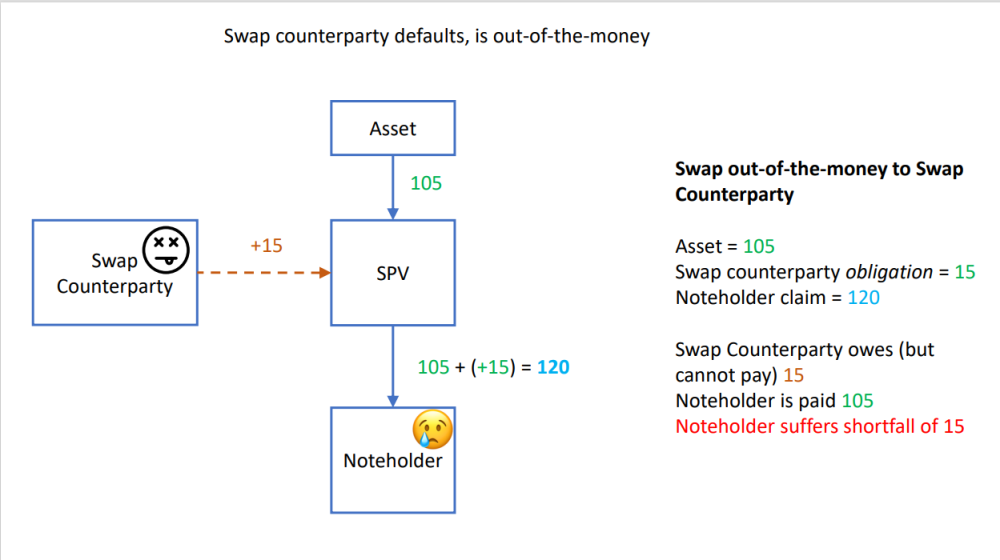

There are two ways this can go: either the Swap Counterparty is out-of-the-money on the swap, in which case it net owes something to the Issuer and has no claim on the security package, so does not really care whether the priority is flipped or not, or it is in-the-money

Given that the ratings goal — the repayment of principal at maturity — would usually be predicated on the credit rating of the swap counterparty, this made little sense. And nor did it have any real effect on the payout of the notes: if your counterparty is bust, and it is owed money, then Q.E.D., the Noteholder’s total claim is limited the the liquidated value of thee bonds minus that payment; if the counterparty owes the SPV money, then no amount of reorganising its place in the security waterfall is going to make any difference since it has no claim against the SPV in the first place.

But it made rating agency analysts feel good, and like they were making a difference, so CDO structurers tended to roll their eyes, but ultimately roll with it.