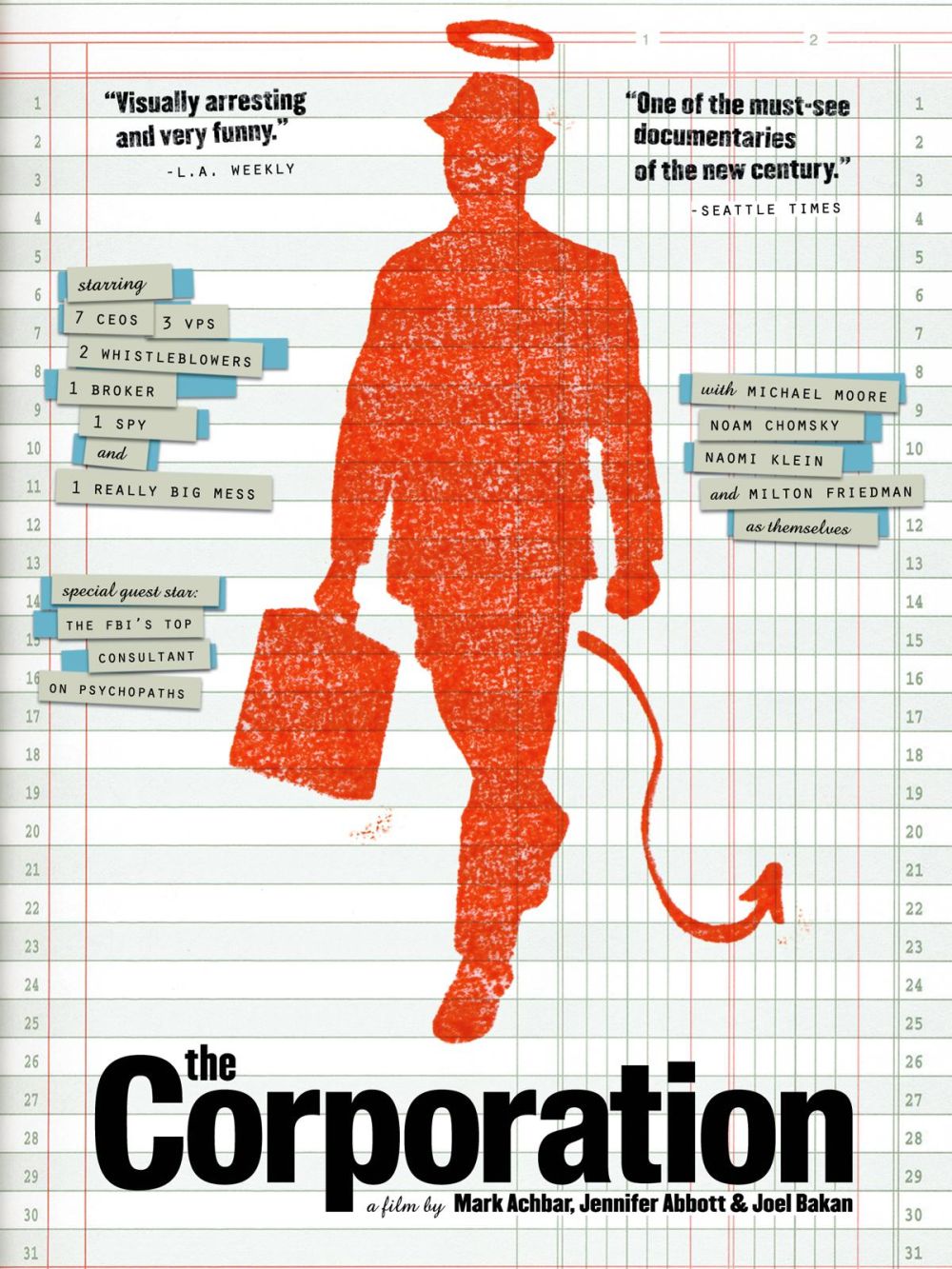

The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power

|

Saturday Night at the Rialto™

|

This review was originally published on January 13, 2006

Slickly edited but all the same simple-minded, misconceived, rubbish.

The film’s political perspective seems to be something like anarcho-syndicalism: the view that a society should be free of all compulsory rules, where all individuals will voluntarily work towards the common goals of the community, unconstrained by the imposed hierarchy of government or capitalism.

Well, it’s an idea that has its merits, and some obvious difficulties too, to the point that while the film-makers are prepared to raise accusing fingers at their capitalist adversaries, they’re notably short of ideas on what to do instead. The best they can come up with is some Froot-Looped Californian backwater which decides, municipally, to discuss whether “whether democracy is even possible when large corporations wield so much wealth and power under law.” The collective gripe, it seems, is with chain restaurants which are opening unchecked in the town (and, presumably, doing steady business with the very same locals). A town meeting is called where these well-intentioned but basically dense people are confronted with some fairly obvious truths:

Quotes one local businessman:

“if you don’t like Pepsi-Cola, Bank of America, well, if you don’t like what they do, don’t use ’em. That’s the way I see the people’s power is.”

That’s it, in a nutshell. That answers the question absolutely, and pretty much every substantial point this documentary has to make. A subsequent participant, who still hasn’t understood it, intones (to cheering):

“People that say that they fear their government. I really hope that they understand that they’re allowed to participate in their government; they’re not allowed to participate in anything the corporations do.”

Well, nothing could be further from the truth: every transaction with a corporation is a direct, financial, participation in what it does, and represents a benefit that it wants and needs, just as a conscious refusal to transact with a corporation represents a lost opportunity. You can participate as often or as rarely as you like, but most people participate many times every day. In the political system, by enormous contrast, the vast majority get a solitary “participation” every four years, a single tick supposed to represent the complicated system of political views held by that single voter; a vote for a candidate who doesn’t win is ignored altogether, and even a vote for the winner, does not guarantee its mandate will be carried out. Some participation in the system that is.

In any case, in their assault on “The Corporation”, the filmmakers engage in some fundamental discombobulations. Consider this one:

Like the Church, the Monarchy and the Communist Party in other times and places, The Corporation is today’s dominant institution.

Stop the tape right there, 0 minutes, 25 seconds on the counter.

In these “other times and places” there was only one Church.[1] There was one Monarchy and one Communist Party. Each was indeed a dominant institution in the community, able to exact compliance by compulsion.

There are millions of corporations, big and small, good and bad, high-minded and scurrilous, and they’re all competing against each other for your dollars. If you don’t like what one does, another will gladly step in. We might quibble about the failure of antitrust rules to prevent market domination — but generally it is a colossal difference. Unless you accept Noam Chomsky’s view that all capitalists are secretly acting in collusion with each other to systematically oppress the masses — you will note there is no “The” Corporation.

The irony is that internally individual Corporations aren’t un-reminiscent of anarcho-syndicalist communes: each is a voluntary assembly of individuals, all of whom share a common purpose, and who are voluntarily acting in accordance with agreed rules with to the betterment of all in the collective. The bigger they get, the more these firms resemble Marxist dictatorships (which is also a feature of anarcho-syndicalist communes!)

I’m sure the filmmakers would rebut this by pointing to the sweatshops in El Salvador, and the anecdote might well implicate an individual corporation — but it doesn’t implicate The Corporation. And let it not be forgotten that corporations - such as those publishing and distributing this film, and Chomsky’s books, were instrumental in identifying and, through the power of the market, discouraging unconscionable practices, in a way that Governments (let alone anarcho-syndicalist communes) manifestly have not been able to do.

In the end it was the market, not the Government, that found Enron out; and the market which bore its losses.[2]

Corporations, like guns, are no more and no less than a reflection of the people who use them. And here is the big point missed, or ignored, by the makers of this film: “the people who use them” means, predominantly, the people who consume their products. That is, US. We, the great, downtrodden masses.

If you don’t understand that, you have no hope purchase on the political debate this film attempts to engage in. Apparently, the makers of this film don’t understand that. If it is true that all Corporations are bad apples, then we need to be looking at ourselves, as owners, shareholders, customers and counterparties of corporations. Blaming the form itself won’t do any good whatsoever.

Finally Michael Moore is wheeled out to congratulate himself, which he does in fine style. But in identifying what he sees as an irony, Moore misses the much larger one in what he is saying:

{{quote| “it’s very ironic that I’m able to do all this and yet ... I’m on networks, I’m distributed by studios that are owned by large corporate entities. Now, why would they put me out there when I am opposed to everything that they stand for? ... It’s because they don’t believe in anything. They put me on there because they know that there are millions of people that want to see my film or watch the TV show and so they’re going to make money ... I’m driving my truck through this incredible flaw in capitalism ...”

But that’s not ironic, and it’s not a flaw in capitalism. It’s the very beauty of capitalism. That’s all the evidence you should need of its democracy, its willingness to allow participation, its agnosticism, its tolerance to any perspective that “the masses” will be interested in. If it will sell, the market will sell it.

The real irony is that Michael Moore — and the makers of this silly documentary — don’t appreciate that very point.

See also

- ↑ In the “other times” to which the filmmakers allude.

- ↑ Honourable mention to the people for bailing out the banks in 2008: This review predates the global financial crisis.