Talk, don’t email: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{A|negotiation|}} If process efficiency is your goal — if, like me, you’ve recently discovered the Toyota Production system and can’t stop thinking about it, if you are..." |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{A|negotiation| | {{A|negotiation|{{image|Onworld and Offworld Comms|png|A quadrant, yesterday. I’m no happier about it that you are, believe me.}}}}Some time in the last decade, negotiators lost the art — the ''joy'' — of the spontaneous two-way conversation. We traded it for the utilitarian transmission of electronic letters, flung like percussive grenades between barricaded trenches. | ||

If we talk at all, we do so by pre-arrangement, in formal, minuted, stage-managed, all-hands conferences. | |||

If you just call | This is a shame. [[JC]] has his theories, as usual, why this happened: for negotiation has been ''formalised'': given parameters, set out in pre-printed instructions, and delegated into greener, cheaper, remoter hands. Negotiation has been transformed from an elaborate, skilful display of tactical swordsmanship to a utilitarian process of mechanically twisting a battery of dials dials until the numbers match. | ||

[[JC]] feels we have either ''lost'' something ''important'' — if there must be a negotiation, then it should be imbued with the spirit of Erroll Flynn — or ''put in'' something ''stupid'' — if the oracular art of negotiation, as a [[commitment signal]], is ''not'' important; if all that is required is mechanical onboarding, a voyage of discovery by means of dial-twisting is just ''[[waste]]'': we should long since have ''solved'' this problem and eradicated the process altogether. | |||

Of course, we are in a dun netherworld between the two states: there is not a risk officer alive with the fortitude to set her controls at a point where clients will just accept them, and clients, in any case, rather like being shown the attention of a joust. | |||

====On swordcraft==== | |||

Thus, ''some'' [[swordcraft]] comes in handy. | |||

But it is hard to practice swordcraft by the exchange of letters. | |||

And, if process efficiency is your goal — and the goal of [[Juniorisation|juniorising]] and the [[Playbook|playbookification]] of negotiation is, without question, process efficiency — then a tendency to break out into a spontaneous fencing bout is surely [[Sod’s law]] at work. | |||

All the same, consider the difference between ''emailing'' the risk controller with your question, waiting 24 hours for her to see it, read it, think about it and send you an elliptical reply that doesn’t quite answer the question — or just [[calling]] her, on the phone, and asking her there and then? | |||

In the first case, there is so much {{wasteprov|waiting}}: the time it takes to compose that [[email]], describe your problem, outline the arguments for and against and your suggested outcome.<ref>This is the perfect means of escalation. Few are as well-formed as this.</ref> Then the {{wasteprov|waiting}}. The ''wondering''. The nervousness. The stress. The heart flutters, as you pick petals off the daisy. Has she seen it? Read it? Will she? It it too soon to nudge her? Will that seem ''needy''? Or [[passive-aggressive]]? Does she even ''care''? | |||

It will ''never'' occur to call. This may be because systematic [[juniorisation]] of the [[negotiation]] function means the negotiators do not have the experience and expertise to talk fluently on their subject matter, and are therefore ''afraid'' to call — and their counterparts, similarly [[juniorised]], will be afraid to pick up.) | |||

====External negotiation==== | |||

The same will obtain, ''a fortiori'', where [[counsel|outside counsel]] are involved. Here there is the added ''frisson'' of the [[agency problem]] working its immeasurable magic. | |||

You are a young associate. Detail is your meat and drink. By schooling yourself on ''[[form]]'', you aspire one day to attain command of ''[[Substance and form|substance]]''. What to do, then, when presented with a draft at significant variance from your client’s commercial expectation? | |||

One of three things can have happened: <blockquote>''One'': ''You'' have misunderstood the transaction. | |||

''Two'': The other side’s counsel has misunderstood the transaction — or sent the wrong documents, or not checked them properly etc. | |||

''Three'': You ''both'' understood the transaction, but there is perfidy afoot. The other side is trying to retrade by stealth. </blockquote>''The overwhelming odds are that it is one of the first two''. Remember [[Hanlon’s razor]]: Do not attribute to ''malice'' things that can just as well be explained by ''stupidity''. There is plenty of stupidity: consider how little ''you'' know, and extrapolate it. ''Everyone is bluffing''. | |||

So, give the benefit of the doubt. ''Call and ask what’s going on''. You will quickly resolve any misunderstandings, and identify that yes, indeed, there has been some ghastly mistake. All can be restored without all-nighters pulled or bullet-riddled drafts exchanged. | |||

Even if it can’t be explained by stupidity, calling is ''still'' the best strategy. You will know soon enough if your counterparty is a rogue. | |||

That call you will save you, your counterpart and your respective clients ''hours'' of time, expense and needless legal clerkship. | |||

But, alack: at once the difficulty of asserting one’s [[legal value]] reveals itself. For if you ''do'' call and thereby avert that cost, time and inconvenience, who will notice? Who will ''appreciate'' how you stilled the night-time dogs, before they had a chance to bark? A paid advisor has little incentive to put in that call. She may be fearful of displaying her own ignorance (should it turn out to be scenario ''one''). If it turns out to be scenario ''two'', she simply spares her opponent’s blushes. Where is the fun in that? Indignantly correcting an opponent’s basic errors is one of the unalloyed joys of commercial practice. | |||

====Communication as an [[infinite game]]==== | |||

{{onworld and offworld negotiation}} | |||

If you just call her, you get the warmth of human contact right off the bat, you get to lay out the issue directly without all that formatting and colour coding, and if you really need to you can (and okay, probably should) send her an [[email]] ''afterwards'' memorialising what you discussed — this can be shorter, since you don’t need to lay out all the explanatory detail, and no need for colour-coding — and also you are not waiting on anything from this email: you have the [[oral]] decision, you can go — the credit dude can confirm in due course. | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Qualities of a good ISDA]] | |||

*[[Let’s go straight to docs]] | |||

*[[Waste]] | *[[Waste]] | ||

*{{wasteprov|Waiting}} | *{{wasteprov|Waiting}} | ||

*[[Circle of escalation]] | |||

*[[Email]] | |||

*[[Data modernism]] | |||

{{ref}}{{nld}} | |||

Latest revision as of 18:24, 18 July 2024

|

Negotiation Anatomy™

|

Some time in the last decade, negotiators lost the art — the joy — of the spontaneous two-way conversation. We traded it for the utilitarian transmission of electronic letters, flung like percussive grenades between barricaded trenches.

If we talk at all, we do so by pre-arrangement, in formal, minuted, stage-managed, all-hands conferences.

This is a shame. JC has his theories, as usual, why this happened: for negotiation has been formalised: given parameters, set out in pre-printed instructions, and delegated into greener, cheaper, remoter hands. Negotiation has been transformed from an elaborate, skilful display of tactical swordsmanship to a utilitarian process of mechanically twisting a battery of dials dials until the numbers match.

JC feels we have either lost something important — if there must be a negotiation, then it should be imbued with the spirit of Erroll Flynn — or put in something stupid — if the oracular art of negotiation, as a commitment signal, is not important; if all that is required is mechanical onboarding, a voyage of discovery by means of dial-twisting is just waste: we should long since have solved this problem and eradicated the process altogether.

Of course, we are in a dun netherworld between the two states: there is not a risk officer alive with the fortitude to set her controls at a point where clients will just accept them, and clients, in any case, rather like being shown the attention of a joust.

On swordcraft

Thus, some swordcraft comes in handy.

But it is hard to practice swordcraft by the exchange of letters.

And, if process efficiency is your goal — and the goal of juniorising and the playbookification of negotiation is, without question, process efficiency — then a tendency to break out into a spontaneous fencing bout is surely Sod’s law at work.

All the same, consider the difference between emailing the risk controller with your question, waiting 24 hours for her to see it, read it, think about it and send you an elliptical reply that doesn’t quite answer the question — or just calling her, on the phone, and asking her there and then?

In the first case, there is so much waiting: the time it takes to compose that email, describe your problem, outline the arguments for and against and your suggested outcome.[1] Then the waiting. The wondering. The nervousness. The stress. The heart flutters, as you pick petals off the daisy. Has she seen it? Read it? Will she? It it too soon to nudge her? Will that seem needy? Or passive-aggressive? Does she even care?

It will never occur to call. This may be because systematic juniorisation of the negotiation function means the negotiators do not have the experience and expertise to talk fluently on their subject matter, and are therefore afraid to call — and their counterparts, similarly juniorised, will be afraid to pick up.)

External negotiation

The same will obtain, a fortiori, where outside counsel are involved. Here there is the added frisson of the agency problem working its immeasurable magic.

You are a young associate. Detail is your meat and drink. By schooling yourself on form, you aspire one day to attain command of substance. What to do, then, when presented with a draft at significant variance from your client’s commercial expectation?

One of three things can have happened:

One: You have misunderstood the transaction.

Two: The other side’s counsel has misunderstood the transaction — or sent the wrong documents, or not checked them properly etc.

Three: You both understood the transaction, but there is perfidy afoot. The other side is trying to retrade by stealth.

The overwhelming odds are that it is one of the first two. Remember Hanlon’s razor: Do not attribute to malice things that can just as well be explained by stupidity. There is plenty of stupidity: consider how little you know, and extrapolate it. Everyone is bluffing.

So, give the benefit of the doubt. Call and ask what’s going on. You will quickly resolve any misunderstandings, and identify that yes, indeed, there has been some ghastly mistake. All can be restored without all-nighters pulled or bullet-riddled drafts exchanged.

Even if it can’t be explained by stupidity, calling is still the best strategy. You will know soon enough if your counterparty is a rogue.

That call you will save you, your counterpart and your respective clients hours of time, expense and needless legal clerkship.

But, alack: at once the difficulty of asserting one’s legal value reveals itself. For if you do call and thereby avert that cost, time and inconvenience, who will notice? Who will appreciate how you stilled the night-time dogs, before they had a chance to bark? A paid advisor has little incentive to put in that call. She may be fearful of displaying her own ignorance (should it turn out to be scenario one). If it turns out to be scenario two, she simply spares her opponent’s blushes. Where is the fun in that? Indignantly correcting an opponent’s basic errors is one of the unalloyed joys of commercial practice.

Communication as an infinite game

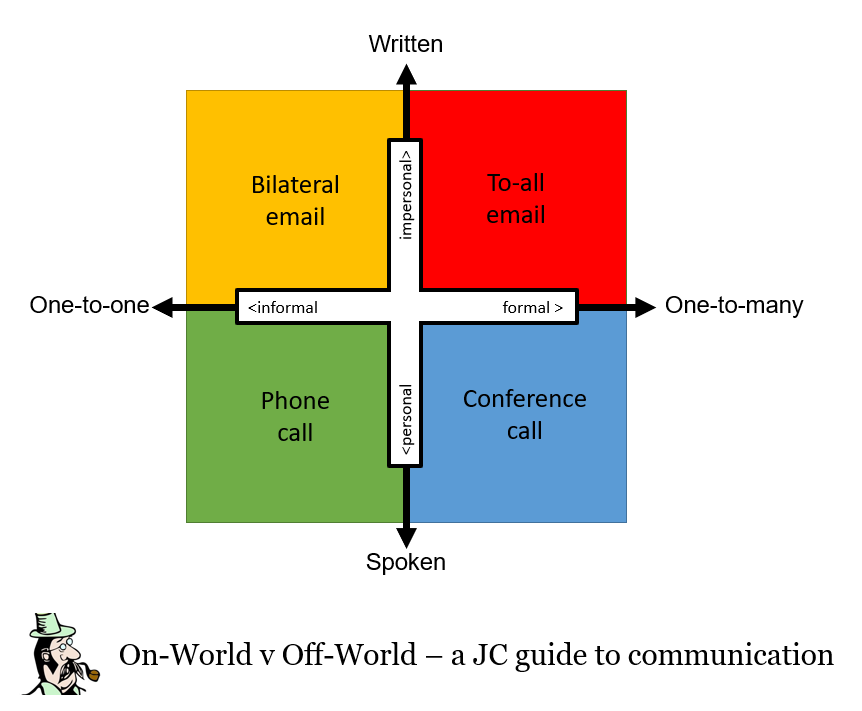

The same dynamic exists in a negotiation. The JC snookered himself into using a four-box quadrant to illustrate this — he has an irrational fear of anything thought-leaders are fond of — but they do seem to fit here because there are two perpendicular axes at play: How many people are you speaking to, and in what medium.

How many

How many people are in your audience? The more there are, the more formal you must be, the more generalised, the less opportunity for there is for nuance and that lubricating milk of human frailty, wit. The more people, the narrower will be their common interest. Plainly, the more people there are, the greater will be the cultural, social and human barriers to unguarded constructive communication.

Fort any communication other than a one-way broadcast, one-to-many is a categorically worse medium for communication than one-to-one.

What medium

Now your “medium of communication” can take a more or less personal, and immediate form. The least personal and immediate communications are written ones (here the message is, literally, removed from the sender’s personality and, even where transmitted immediately, need not be answered in real time). The most personal and immediate ones are in actual, analogue person — like that ever happens these days — and failing that, a video call where you can see and hear nuance, then an audio call where you can just hear it. But any of these is vastly superior to written communication.

On constructive and defensive communication

In terms of our Onworld/Offworld distinction let us make some value judgments: whether we like it or not, the offworld we inhabit is a complex, non-linear one. Personal, creative, immediate, and substantive communications beat impersonal, delayed, and formalistic ones. Constructive communicators — players of “keepy-uppy” and like-minded infinite games — communicate to get along, and they therefore get on better than those who communicate defensively — who play backward-looking, bounded, aero-sum, finite games.

But the sorts of communications you favour depend what sort of, and how good, a communicator you are. Constructive, expert, imaginative, pragmatic, empathetic participants will be good at immediate interpersonal communications. Negative, defensive, inexpert, heartless, wooden communicators tend to be better at delayed, written communications.

Why would you design your communication channels to favour negative, unempathetic, inexpert, defensive people?

If you just call her, you get the warmth of human contact right off the bat, you get to lay out the issue directly without all that formatting and colour coding, and if you really need to you can (and okay, probably should) send her an email afterwards memorialising what you discussed — this can be shorter, since you don’t need to lay out all the explanatory detail, and no need for colour-coding — and also you are not waiting on anything from this email: you have the oral decision, you can go — the credit dude can confirm in due course.

See also

- Qualities of a good ISDA

- Let’s go straight to docs

- Waste

- Waiting

- Circle of escalation

- Data modernism

References

- ↑ This is the perfect means of escalation. Few are as well-formed as this.