Innovation paradox: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (51 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

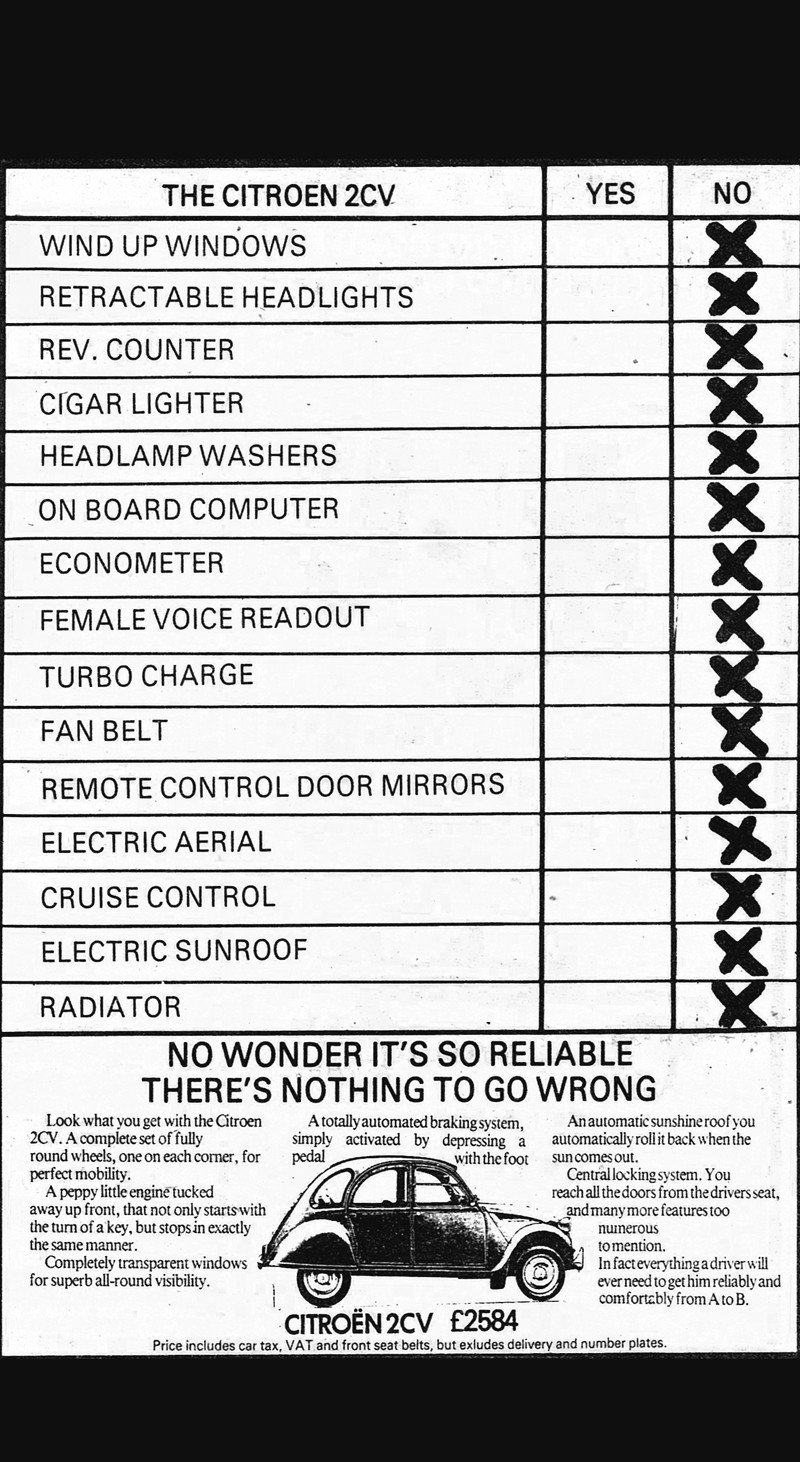

{{a|tech|}} | {{a|tech|{{image|2cv ad|jpg|{{maxim|To increase efficiency, seek to remove technology from the workplace}}}} }}{{quote| | ||

{{frog and scorpion}} | |||

:—Folk tale}} | |||

{{quote|{{maxim|To increase efficiency, seek to remove technology from the workplace}}. | |||

::— The [[JC]]’s maxims for a happy life.}} | |||

Behold, the [[Innovation paradox]]: Why does [[legaltech]] promise so much but deliver so little? | |||

''Is'' it a [[paradox]], though? | |||

Things weren’t so bad in 1975. There was a natural limit on legal wrangling. Making any edit during a negotiation would mean ''retyping the entire page''. And posting it in. And having it posted back. In carbon triplicate. | |||

Hence, [[negotiation]] was necessarily bounded by the effort and time in recreating and circulating the document — by ''post''. The lawyer’s art was to say something once, clearly and precisely. Since any editing was clearly [[waste]]ful, superficial amendment was not the apparently<ref>But not actually. See: ''[[Waste]]''.</ref> costless frippery it is today. | |||

By the nineties, the office manager’s refrain “''we don’t pay lawyers to type, son''” had lost its force. We had terminals on our desks, next to the executive model ''Dictaphone{{tm}}''. By the millennium, we didn’t even need a business case ''to get the internet''. | |||

Suddenly, we could spawn docs, tweak clauses, shove in [[rider|riders]] — ''endlessly'' futz around with words. Generating and sending documents was free and instantaneous. It was like the sorcerer’s apprentice. {{author|Stanley Fish}} even wrote a [[How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One - Book Review|book]] about it. | |||

Suddenly [[contract]]s were concluded in a flash, right? | |||

''Wrong''. | |||

Far from ''accelerating'' [[negotiation]]s, [[technology]] gave us free rein to indulge our yen for pedantry. [[Cross acceleration|''Cross''-acceleration]], if you like. Negotiations got longer. The issues got more prolix. We argued about trifles because we ''could''. We danced on the head of a pin, because we ''could''. | |||

And technology lowered the bar: certain [[contract]]s, which previously could not justify their own existence, let alone human negotiation, could now be thrashed out in infinite, infinitesimal detail. We argued about not just trifles, but pavlovas, puddings, flans, flummeries —even fricking self-saucing sponges. ''Because we could''. | |||

''That’s what lawyers do. [[It is not in my nature|It is in our nature]]''. | |||

Yet, yet yet: many painful artefacts of the analogue era — the gremlins and hair-balls you would expect [[technology]] to remove — ''persist''. To this day, we ''still'' have [[side letter]]s and [[amendment agreement]]s. We ''still'' write: “[[this page is intentionally left blank]]”. We — well, our [[US Attorney|American]] friends, at any rate — ''still'' say “[[this clause is reserved]],” as if we haven’t noticed [[Microsoft Word]] has an automatic paragraph numbering system.<ref>Albeit one that almost no-one knows how to use. It is a truth universally acknowledged that no [[lawyer]] on God’s earth can competently format a document in [[Microsoft Word]].</ref> Not only has [[legaltech]] ''failed'' to remove legacy [[Complication|complications]], ''it has created entirely new ones.'' | |||

The | *Are there any fewer lawyers today? No.<ref>There are more than ever: [https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/news/warning-as-number-of-solicitors-tops-140000/5063349.article The number of practising solicitors in England and Wales has reached another all-time high] — ''Law Gazette''.</ref> | ||

* | *Are more deals being done? No.<ref>The number of M&A deals peaked in — you guessed it - [[Global financial crisis|2007]]: [https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-and-acquisitions-statistics/ Number & value of M&A deals worldwide since 2000] — ''The Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances''.</ref> | ||

*Are there more words? My oath there are.<ref>Now, to be sure, I have no data for this last assertion — where would you get them? — but there is no doubt the variety, length and textual density of legal [[contract]]s ''exploded'' after 1990.</ref> | |||

The more [[technology]] we have thrown at “[[the legal problem]]”, the longer and crappier our [[contract]]s have become. A curious type might pause to wonder ''why''. Surprisingly few have.<ref>Not even those professionally motivated to do so: futurologists of the law have forged whole academic careers by predicting a [[The Singularity is Near - Book Review|legal dystopia]] which seems, in thirty years, only sclerotically to have got any nearer. [[A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond - Book Review|A world without work]]? Fat chance.</ref> | |||

Why isn’t technology helping? | |||

Let me hazard a guess. To be sure, Andy has given, but it wasn’t Bill who took away.<ref>Let me [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_and_Bill%27s_law Google that cultural reference for you].</ref> So who was it? ''All of us''. You and me, readers: we [[legal eagle|nit-picky, care-worn, pedantic attorneys]]. It is a function of the [[Agency problem|incentives]] at play. We [[lawyer]]s and [[negotiator]]s are remunerated by the time we take and the [[value]] we add. We “add value” in the shape of ''words''. We put them in and we take them out. We are rewarded for the complexity and sophistication of our analysis. | |||

That means, we ''fiddle''. | |||

''Lawyers don’t want to simplify.'' Lawyers don’t ''want'' to truncate. ''[[It is not in my nature|That is not their nature]]''. It is ''contrary'' to their nature. ''That is not what lawyers will use technology for.'' Lawyers will use technology to find ''new'' complexities. To eliminate ''further'' risks. To descend closer to the [[fractal]] shore of [[risk]] that it is their sacred quest to police. | |||

If your principle goal is to simplify, [[technology]] will help. But if your goal is livelihood-preservation through confusion, obfuscation and distraction, ''[[technology]] is your weapon''. Thus has it ''brilliantly'' enabled lawyers to showcase the sophistication and complexity of their syntax. In a nutshell: We use [[technology]] to ''indulge'' ourselves.<ref>There is a serious point here for people who argue that technology implementations should be driven as far as possible by users at the coalface. And that is to bear in mind that the interests of users at the coalface are not necessarily aligned with those of the organisation for which they are working.</ref> | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[ | *[[e-discovery]] | ||

{{c|paradox}} | *[[Boilerplate]] | ||

*[[ClauseHub]] | |||

*[[Innovation]] | |||

*[[Natural language processing]] | |||

*[[Legaltech]] | |||

{{c|paradox}} | |||

{{ref}} | |||

Latest revision as of 13:30, 14 August 2024

|

JC pontificates about technology

An occasional series.

|

A scorpion asks a frog to carry it across the river. The frog hesitates, afraid of being stung.

“But,” says the scorpion, “if I sting you, we will both drown”.

“I see!” says the frog. “Hop on!”

They wade into the river. Midway across, the scorpion stings the frog.

With his dying breath, the frog cries, “Why did you do that? Now we both will die!”

The scorpion shrugs. “It’s in my nature.”

- —Folk tale

To increase efficiency, seek to remove technology from the workplace.

- — The JC’s maxims for a happy life.

Behold, the Innovation paradox: Why does legaltech promise so much but deliver so little?

Is it a paradox, though?

Things weren’t so bad in 1975. There was a natural limit on legal wrangling. Making any edit during a negotiation would mean retyping the entire page. And posting it in. And having it posted back. In carbon triplicate.

Hence, negotiation was necessarily bounded by the effort and time in recreating and circulating the document — by post. The lawyer’s art was to say something once, clearly and precisely. Since any editing was clearly wasteful, superficial amendment was not the apparently[1] costless frippery it is today.

By the nineties, the office manager’s refrain “we don’t pay lawyers to type, son” had lost its force. We had terminals on our desks, next to the executive model Dictaphone™. By the millennium, we didn’t even need a business case to get the internet.

Suddenly, we could spawn docs, tweak clauses, shove in riders — endlessly futz around with words. Generating and sending documents was free and instantaneous. It was like the sorcerer’s apprentice. Stanley Fish even wrote a book about it.

Suddenly contracts were concluded in a flash, right?

Wrong.

Far from accelerating negotiations, technology gave us free rein to indulge our yen for pedantry. Cross-acceleration, if you like. Negotiations got longer. The issues got more prolix. We argued about trifles because we could. We danced on the head of a pin, because we could.

And technology lowered the bar: certain contracts, which previously could not justify their own existence, let alone human negotiation, could now be thrashed out in infinite, infinitesimal detail. We argued about not just trifles, but pavlovas, puddings, flans, flummeries —even fricking self-saucing sponges. Because we could.

That’s what lawyers do. It is in our nature.

Yet, yet yet: many painful artefacts of the analogue era — the gremlins and hair-balls you would expect technology to remove — persist. To this day, we still have side letters and amendment agreements. We still write: “this page is intentionally left blank”. We — well, our American friends, at any rate — still say “this clause is reserved,” as if we haven’t noticed Microsoft Word has an automatic paragraph numbering system.[2] Not only has legaltech failed to remove legacy complications, it has created entirely new ones.

- Are there any fewer lawyers today? No.[3]

- Are more deals being done? No.[4]

- Are there more words? My oath there are.[5]

The more technology we have thrown at “the legal problem”, the longer and crappier our contracts have become. A curious type might pause to wonder why. Surprisingly few have.[6]

Why isn’t technology helping?

Let me hazard a guess. To be sure, Andy has given, but it wasn’t Bill who took away.[7] So who was it? All of us. You and me, readers: we nit-picky, care-worn, pedantic attorneys. It is a function of the incentives at play. We lawyers and negotiators are remunerated by the time we take and the value we add. We “add value” in the shape of words. We put them in and we take them out. We are rewarded for the complexity and sophistication of our analysis.

That means, we fiddle.

Lawyers don’t want to simplify. Lawyers don’t want to truncate. That is not their nature. It is contrary to their nature. That is not what lawyers will use technology for. Lawyers will use technology to find new complexities. To eliminate further risks. To descend closer to the fractal shore of risk that it is their sacred quest to police.

If your principle goal is to simplify, technology will help. But if your goal is livelihood-preservation through confusion, obfuscation and distraction, technology is your weapon. Thus has it brilliantly enabled lawyers to showcase the sophistication and complexity of their syntax. In a nutshell: We use technology to indulge ourselves.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ But not actually. See: Waste.

- ↑ Albeit one that almost no-one knows how to use. It is a truth universally acknowledged that no lawyer on God’s earth can competently format a document in Microsoft Word.

- ↑ There are more than ever: The number of practising solicitors in England and Wales has reached another all-time high — Law Gazette.

- ↑ The number of M&A deals peaked in — you guessed it - 2007: Number & value of M&A deals worldwide since 2000 — The Institute for Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances.

- ↑ Now, to be sure, I have no data for this last assertion — where would you get them? — but there is no doubt the variety, length and textual density of legal contracts exploded after 1990.

- ↑ Not even those professionally motivated to do so: futurologists of the law have forged whole academic careers by predicting a legal dystopia which seems, in thirty years, only sclerotically to have got any nearer. A world without work? Fat chance.

- ↑ Let me Google that cultural reference for you.

- ↑ There is a serious point here for people who argue that technology implementations should be driven as far as possible by users at the coalface. And that is to bear in mind that the interests of users at the coalface are not necessarily aligned with those of the organisation for which they are working.