Template:M summ Equity Derivatives 8.7: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Well, I did, anyway. | Well, I did, anyway. | ||

===How to charge for [[equity derivatives]]=== | |||

{{equity derivative charging}} | |||

Revision as of 14:43, 28 September 2020

Equity Amounts, then. Straightforward enough: Take your Equity Notional Amount — helpfully filled out in the Confirmation — multiply it by the Rate of Return, being the performance of the underlying share over the period in question — and there’s your number.

The basics: a worked example.

Let’s put some numbers on this, because, as with many of the finer creations of ISDA’s crack drafting squad™, there is quite a lot of buried technology in there to unpack.

The first component is the Rate of Return. This is a calculation of the performance of the Share over the period, times a Multiplier which might apply if you are doing some kind of kooky leveraged trade, but more likely will account for capital gains or stamp duty payable by the broker on the underlying hedge — so you might expect something like 85%. But that makes the mathematics too complicated for this old fellow, so let’s call the Multiplier 100%, so you can ignore it, and say the Initial Price is 100. And let’s do two scenarios: where the stock has gone up — here say the Final Price is 105, and where the stock has gone down — here, say the Final Price is 95.

The Rate of Return formula is (Final Price - Initial Price)/Initial Price) * Multiplier, which works out as:

- Where the stock went up: (105-100)/100 * 100% = 5/100 = +5%.

- Where the stock went down: (95-100)/100 * 100% = -5/100 = -5%.

Now to calculate your Equity Amount, we take the Equity Notional Amount (for ease of calculation, say USD1,000,000?) and times it by the Rate of Return:

- Where the stock went up: USD1,000,000 * +5% = USD+50,000.

- Where the stock went down: USD1,000,000 * -5% = USD-50,000.

Shorts, longs and flexi-transactions

Now as you know, the ISDA Master Agreement is a bilateral construct — In a funny way, a bit Bob Cunis like that — and while the equity derivatives market is largely conducted between dealers and their clients, this doesn’t mean the dealer is always the Equity Amount Payer. The client — as often as not, a hedge fund — is as likely to be taking a short position — locusts, right? — as a long one. One does this by reversing the roles of the parties in the Confirmation: The Equity Amount Payer for a long transaction will be a dealer. The Equity Amount Payer for a short transaction will be the fund.

So much so uncontroversial. But then there are flexi-transactions: in these modern times of high-frequency trading, unique transaction identifiers and trade and transaction reporting, dealers and their clients are increasingly interested in consolidating the multiple trade impulses they have on the same underlyer into single positions and single transactions: this makes reconciling reporting far easier, and also means you don’t have to be assigning thousands of UTIs every day — at a couple of bucks a throw — to what is effectively a single stock position.

What does this have to do with Equity Notional Amounts? Well, the Equity Notional Amount of that single “position” transaction is now a moving target. A short trade impulse on a (larger) existing long position will reduce the Equity Notional Amount, but it won’t necessarily change who is the Equity Amount Payer, unless the total notional of the position flips from positive to negative. Then it will. This is kind of weird if you stand back and look at it from a stuffy, theoretical point of view, but once you slip into that warm negligee of pragmatism in which almost all legal eagles love to drape themselves, you get over it.

Well, I did, anyway.

How to charge for equity derivatives

Remember our theory of the game, synthetic PB ninjas: synthetic PB is just margin lending done with swaps. That should offer some clues about how clients pay for it. The economics are the same. This is about the economic cost of entering margin loans, not the economic exposure you have to the stock you have bought. Though that does come into it.

Physical prime brokerage

Physical longs

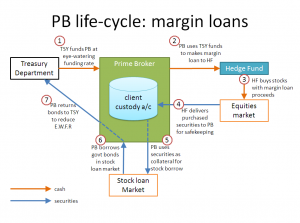

In a physical margin loan — representing a long equity position — the client expects two types of cost:

- Financing: The financing costs it will incur from its prime broker in borrowing the money it needs to buy the stock, and

- Commission: The brokerage commissions it will incur from its equity broker in buying (and when it is ready to, selling again) the stock.

To offset its costs, the prime broker can rehypothecate the stock, which it holds in custody for the client. Now when it does so, the PB does not take price risk to the stock: remember; it does not have a directional view on the stock. So it will not sell the stock outright, but more likely will use it as collateral in the market, to raise cash (under a repo) or high-quality assets (under a stock loan). If the stock increases in value, happy days for all concerned: the PB will receive more cash, and at the limit may reach its rehypothecation limit and have to return some of the rehypothecated stock to the client. If the stock declines in value, the PB will be able to raise less cash against it, but will be able to call for more margin from the client.

Physical shorts

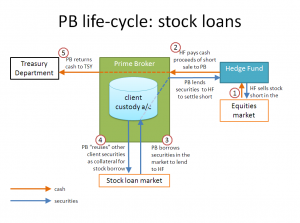

In a short position on margin, the client expects the following costs:

- Financing: The financing costs it will incur from its prime broker under the stock loan by which it borrows the security it wants to short, and

- Commission: The brokerage commissions it will incur from its equity broker in selling (and when it is ready to, buying back) the stock it has borrowed.

Here the client also has something it can offer the prime broker to offset its internal funding costs: the proceeds of sale of the borrowed stock, which it banks in its cash account with the PB. That has the effect of reducing the client’s overall indebtedness. Now its exposure moves around under the stock loan with the prime broker. If the stock increases in value, the client’s liability under the stock loan also increases, and the PB will call for margin. If the stock decreases in value, happy days for the client: the value of its stock loan liability (to return that stock to the PB) will decline, meaning its overall indebtedness declines meaning at the limit the PB may reach its rehypothecation limit and have to return some of the rehypothecated stock to the client.

Synthetic prime brokerage

Under an equity swap, the client never actually buys the stock, but it puts on a Transaction with its prime broker that replicates the economics of doing so, on margin:

Synthetic longs

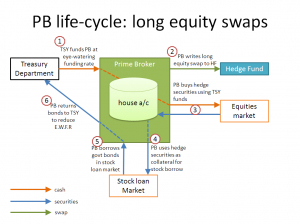

In a long synthetic equity swap — the synthetic equivalent of a physical long, of course — the client expects two types of cost:

- Financing: The financing costs its swap dealer incurs in borrowing the money it needs to buy its hedge position, and

- Commission: The equivalent of brokerage commissions it would pay its dealer for executing the trade (and when it is ready to, terminating it).

To offset its costs, the swap dealer can raise finance against its Hedge Position, which it owns outright, in the repo/stock loan market. since the stock hedges its swap position, the dealer will not sell the stock outright, but will use it as collateral in the market, to raise cash (under a repo) or high-quality assets (under a stock loan). If the stock increases in value, happy days: the dealer will get more cash, but will need that for variation margin it owes its client to the swap. If the stock declines in value, the dealer will be able to raise less cash against it, but will be able to call for more variation margin from the client.

Synthetic shorts

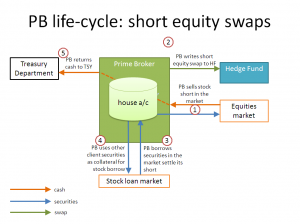

In a short synthetic equity swap — the synthetic equivalent of a physical short, of course — the client expects the following costs:

- Financing: The financing costs the swap dealer incurs under the stock loan the dealer executes as a Hedge Position to the short swap, under which it borrows the physical underlying security and sells it short, and

- Commission: The equivalent of brokerage commissions it would pay its dealer for executing the trade (and when it is ready to, terminating it).

- Here the dealer obtains the proceeds of short sale of its Hedge Position and it can use these to offset its internal funding costs of collateralising its stock loan hedge. Now ther client’s exposure under the short swap tracks the swap dealer’s exposure under the stock loan Hedge Position: If the underlier increases in value, the client’s liability under the short and the dealer’s liability under its stock loan hedge increase, and the dealer will call the client for variation margin, which it can use to meet its margin call on its hedge. If the stock decreases in value, happy days: the dealer will receive collateral back from its stock loan hedge counterparty, but will have to pay out variation margin to the client.