Risk taxonomy: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

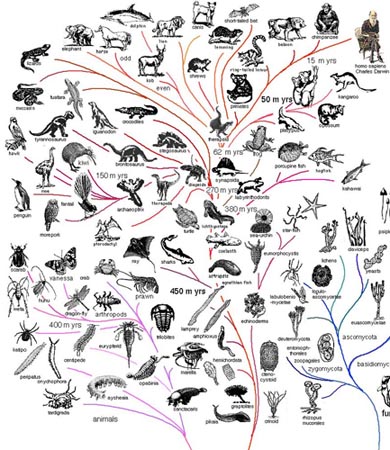

{{a|risk|}}A fine occupation for the idle [[Mediocre lawyer|lawyer]]: Describing, and grouping in relation to each other, the entire catalog of risks that face your undertaking, as if unrealised legal hazards can be ranked, boxed and sorted like the phyla of butterflies, tits or thrush. | {{a|risk| | ||

[[File:Taxonomy.jpg|450px|frameless|center]] | |||

}}A fine occupation for the idle [[Mediocre lawyer|lawyer]]: Describing, and grouping in relation to each other, the entire catalog of risks that face your undertaking, as if unrealised legal hazards can be ranked, boxed and sorted like the phyla of butterflies, tits or thrush. | |||

This exercise can occupy as little — a breakout session on an away-day — or as much — the permanent task of a dedicated division in the department — of your firm's intellectual capacity as you have going spare: organisations that run to the bureaucratic<ref>''You'' know who you are.</ref> may become so swooned by this notion that they can find little time to do anything else. For how can one asses the risks of a transaction if one doesn't know from which family of what genus in what species it hails? | This exercise can occupy as little — a breakout session on an away-day — or as much — the permanent task of a dedicated division in the department — of your firm's intellectual capacity as you have going spare: organisations that run to the bureaucratic<ref>''You'' know who you are.</ref> may become so swooned by this notion that they can find little time to do anything else. For how can one asses the risks of a transaction if one doesn't know from which family of what genus in what species it hails? | ||

Revision as of 17:22, 2 September 2019

|

Risk Anatomy™

|

A fine occupation for the idle lawyer: Describing, and grouping in relation to each other, the entire catalog of risks that face your undertaking, as if unrealised legal hazards can be ranked, boxed and sorted like the phyla of butterflies, tits or thrush.

This exercise can occupy as little — a breakout session on an away-day — or as much — the permanent task of a dedicated division in the department — of your firm's intellectual capacity as you have going spare: organisations that run to the bureaucratic[1] may become so swooned by this notion that they can find little time to do anything else. For how can one asses the risks of a transaction if one doesn't know from which family of what genus in what species it hails?

The problem with risk taxonomies

Jolly Contrarian has two reservations about risk taxonomies:

The false comfort blanket

Any taxonomy, like a map, can only document the territory you already know, have raked over, surveyed and measured it. Known knowns. Stables from which the horse has bolted, so to say.

This is of a piece with the common lawyer’s usual mode of reasoning, the doctrine of precedent, whose organising principle is to move forward by exclusive reference to what lies behind. This is all very well in times of plenty, when the tide is rising, all boats are floating, those swimming nude are safely concealed from the neck down and all is well in the world. Here, the world behaves according to the narrative we have supplied it — we are in a period of “normal science”[2]. But by the same token, the acute risks are in abeyance. Aslan is not on the move. Even if you left the door open, the horse has a nosebag full of hay and isn’t going anywhere.

But what happens when our carefully constructed narrative falls apart? Those stressed scenarios in which, as the old saw has it, I’ll be gone, you’ll be gone, and black swans will be angrily flapping about. Then, your paradigm has failed. People around you are losing their heads and blaming it on you and your stupid taxonomy, which suddenly isn’t working.

See also: known knowns

It’s a narrative

Any taxonomy is a narrative. Like any hierarchical organising system, a taxonomy commits you to one way of looking at the world, at the expense of all others. Now this a necessary evil when it comes to concrete physical things, like books: the Dewey decimal system is a single hierarchy — a narrative — by necessity: a physical thing cannot be in two places at once. So all library users agree a common taxonomy (subject matter, not author, or title, or publisher) and, for better or worse, stick to it.

But legal risks aren’t concrete things. They have no concrete existence at all. They’re amorphous, will-o’-the-wisp, they are black swans — the biggest risks don’t necessarily exist on the frame of consciousness of even the most paranoid risk controller before they happen. Indeed, that is the risk. New risks will, by definition, inhibit the seams, cracks and weak joints of your narrative — they will prompt your change in narrative. Their scars will prompt you to build a new stable around the space where the horse you didn’t even know was there turns out to have been standing before it bolted. Subtly, the general counsel will mandate a new service catalog. He will commission a working group to build a new risk taxonomy.

See also

References

- ↑ You know who you are.

- ↑ Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. If you take one book recommendation from the JC, make it this one. Or The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.