Limited recourse: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|contract|}}Of a {{tag|contract}}, that the [[obligor]]’s obligations under it are limited to a defined pool of assets. You see this a lot in [[repackaging]]s, [[securitisation]]s and other structured transactions involving [[espievie]]s. | {{a|contract| | ||

[[File:Fidgety phillip.jpg|450px|thumb|center|What happens if you do not concentrate on your debt extinction language]] | |||

}}Of a {{tag|contract}}, that the [[obligor]]’s obligations under it are limited to a defined pool of assets. You see this a lot in [[repackaging]]s, [[securitisation]]s and other structured transactions involving [[espievie]]s. [[Security]] and [[limited recourse]] are fundamental structural aspects of contracts with [[Special purpose vehicle]]s and [[investment fund]]s. | |||

=== | ===The basic idea=== | ||

[[ | Investment funds and structured note issuance vehivles tend to be purpose-built single corporations with no other role in life. They issue shares or units to investors and with the proceeds, buy securities, make investments and enter swaps, loans and other transactions with their brokers. The brokers will generally be [[Capital structure|structurally senior]] to the fund’s investors (either as unsecured [[creditor]]s, where the investors are [[Shareholder|shareholders]], or as higher-ranking secured creditors, where the investors are also [[secured creditor|secured creditors]]). | ||

So the main reason for limiting the [[broker]]’s recourse to the [[SPV]]’s assets is not to prevent the broker being paid what it is owed. It is to stop the [[SPV]] going into formal bankruptcy procedures ''once all its assets have been liquidated and distributed [[pari passu]] to creditors''. At this point, there is nothjing left to pay anyone, so it is academic. | |||

Now, why would a [[broker]] want to put an empty [[SPV]] — one which has already handed over all its worldly goods to its creditors — into liquidation? Search me. Why, on the other hand, would the directors of that empty [[SPV]], bereft as it is of worldly goods, be anxious for it ''not'' to go into liquidation? Because their livelihoods depend on it: being directors of a bankrupt company opens them to allegations or reckless trading, which may bar them from acting as directors in their jurisdiction. Since that’s their day job, it’s a bummer. | |||

But haven’t they been, like, reckless trading? No. Remember, we are in the [[parallel universe]] of [[SPV]]s. Unlike normal commercial undertakings, [[SPV]]s run on autopilot. They are designed to give exposure, exactly, to the pools of assets and liabilities they hold. That’s the deal. Everyone trades with [[SPV]]s on that understanding. The directors are really nominal figures: they outsource executive and trading decisions to an [[investment manager]]. Their main job is to ensure accounts are prepared and a return filed each year. They are not responsible for the trading strategy that drove the [[espievie]] into the wall.<ref>The [[investment manager]] is. So should ''she'' be barred from managing assets? THIS IS NOT THE TIME OR THE PLACE TO DISCUSS.</ref> | |||

So all an [[investment fund]]’s [[limited recourse]] clause really needs to say is: | |||

:''Our recourse against the Fund will be limited to its assets, rights and claims. Once they have been finally realised and their net proceeds applied under the agreement, the Fund will owe us no further debt and we may not take any further steps against it to recover any further sum.'' | |||

But | But, as we shall see, sometimes [[asset manager]]s can be a malign influence, and try to further limit this. | ||

===Variations=== | |||

So there are different varieties of limited recourse; some more fearsome than others: | |||

===Multi-issuance [[repackaging]] vehicles: secured, limited recourse=== | |||

In the world of multi-issuance [[repackaging]] [[SPV]]s, [[secured, limited recourse obligation|secured limited recourse]] obligations are ''de rigueur''. They save the cost of creating a whole new vehicle for each trade, and really only do by [[contract]] what establishing a brand new [[espievie]] for each deal would do through the exigencies of corporation law and the [[corporate veil]]. That said, with [[Segregated portfolio company|segregated cell companies]], you can more or less do this, through the exigencies of the corporate veil, inside a single [[espievie]]. But I digress. | |||

With [[secured, limited recourse obligation]]s there is a ''quid pro quo'': creditors agree to limit their claims to the liquidated value of the secured assets underlying the deal (usually a [[par asset swap]] package), but in return, the issuer grants a first-ranking security over those assets in favour of the creditors, stopping any interloper happening by and getting its mitts on them. | |||

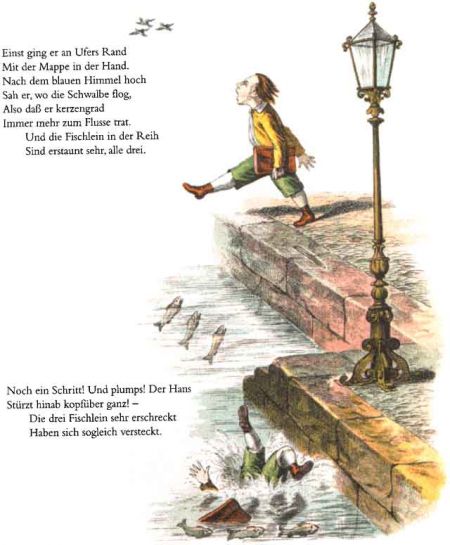

Over the years the secured, limited recourse technology has been refined and standardised, and now plays little part in the education of a modern-day structured finance lawyer, though, at his mother’s knee, he might once have been told fairy stories about what became of poor Fidgety Phillip when he carelessly put “extinction” rather than “no debt due” in a pricing supplement on his way home from school and burned to death.<ref>Come to think of it he may have forgotten to file a [[Slavenburg]].</ref> | |||

===General limited recourse for investment funds=== | |||

Where you are facing an investment fund held by equity investors it is slightly — but not very — different. Generally, there is no security, since there’s no question of [[ring-fencing]] separate pools of assets. (But investment managers can get in the way and steal options, so be on your guard — see below). | |||

'''Limiting recourse to the fund’s entire pool of assets''': A provision which says “once all the fund’s assets are gone, you can’t put it into bankruptcy”, is essentially harmless, seeing as once all the fund’s assets are gone there’s no ''point'' putting it into bankruptcy. This is the same place you would be with a single-issue [[repackaging]] vehicle: the [[corporate veil]] does the work anyway. | |||

==='''Limiting recourse to assets managed by an agent'''=== On the other hand, limiting recourse to a pool of assets ''within'' a single fund legal entity — say to those managed by a single [[investment manager]] (some funds subcontract out management of their portfolios to multiple asset managers) — being a ''subset'' of the total number of assets owned by the fund — is a different story altogether. This, by sleepy market convention, has become a standard part of the furniture, but to the [[JC]] and his friends and relations, seems ''batshit insane''. | |||

So firstly, the investment manager is an [[agent]]. An [[agent]] isn’t liable ''at all'' for ''any'' of its [[principal]]s’ obligations. It is a mere [[intermediary]]: the [[JC]] have waxed long and hard enough about that elsewhere; suffice to say the concept of [[agency]] is one of those things we feel [[Legal concepts all bankers should know|''everyone'' in financial services should know]]; this is not one to drop-kick to your [[legal eagle]]s: it is fundamental to the workings of all finance. | |||

So why would an agent seek to limit its principal’s liability to the particular pool of assets that principal has allocated to that agent? | |||

===[[Limited recourse]] formulations=== | ===[[Limited recourse]] formulations=== | ||

Revision as of 08:42, 15 October 2020

Of a contract, that the obligor’s obligations under it are limited to a defined pool of assets. You see this a lot in repackagings, securitisations and other structured transactions involving espievies. Security and limited recourse are fundamental structural aspects of contracts with Special purpose vehicles and investment funds.

The basic idea

Investment funds and structured note issuance vehivles tend to be purpose-built single corporations with no other role in life. They issue shares or units to investors and with the proceeds, buy securities, make investments and enter swaps, loans and other transactions with their brokers. The brokers will generally be structurally senior to the fund’s investors (either as unsecured creditors, where the investors are shareholders, or as higher-ranking secured creditors, where the investors are also secured creditors).

So the main reason for limiting the broker’s recourse to the SPV’s assets is not to prevent the broker being paid what it is owed. It is to stop the SPV going into formal bankruptcy procedures once all its assets have been liquidated and distributed pari passu to creditors. At this point, there is nothjing left to pay anyone, so it is academic.

Now, why would a broker want to put an empty SPV — one which has already handed over all its worldly goods to its creditors — into liquidation? Search me. Why, on the other hand, would the directors of that empty SPV, bereft as it is of worldly goods, be anxious for it not to go into liquidation? Because their livelihoods depend on it: being directors of a bankrupt company opens them to allegations or reckless trading, which may bar them from acting as directors in their jurisdiction. Since that’s their day job, it’s a bummer.

But haven’t they been, like, reckless trading? No. Remember, we are in the parallel universe of SPVs. Unlike normal commercial undertakings, SPVs run on autopilot. They are designed to give exposure, exactly, to the pools of assets and liabilities they hold. That’s the deal. Everyone trades with SPVs on that understanding. The directors are really nominal figures: they outsource executive and trading decisions to an investment manager. Their main job is to ensure accounts are prepared and a return filed each year. They are not responsible for the trading strategy that drove the espievie into the wall.[1]

So all an investment fund’s limited recourse clause really needs to say is:

- Our recourse against the Fund will be limited to its assets, rights and claims. Once they have been finally realised and their net proceeds applied under the agreement, the Fund will owe us no further debt and we may not take any further steps against it to recover any further sum.

But, as we shall see, sometimes asset managers can be a malign influence, and try to further limit this.

Variations

So there are different varieties of limited recourse; some more fearsome than others:

Multi-issuance repackaging vehicles: secured, limited recourse

In the world of multi-issuance repackaging SPVs, secured limited recourse obligations are de rigueur. They save the cost of creating a whole new vehicle for each trade, and really only do by contract what establishing a brand new espievie for each deal would do through the exigencies of corporation law and the corporate veil. That said, with segregated cell companies, you can more or less do this, through the exigencies of the corporate veil, inside a single espievie. But I digress.

With secured, limited recourse obligations there is a quid pro quo: creditors agree to limit their claims to the liquidated value of the secured assets underlying the deal (usually a par asset swap package), but in return, the issuer grants a first-ranking security over those assets in favour of the creditors, stopping any interloper happening by and getting its mitts on them.

Over the years the secured, limited recourse technology has been refined and standardised, and now plays little part in the education of a modern-day structured finance lawyer, though, at his mother’s knee, he might once have been told fairy stories about what became of poor Fidgety Phillip when he carelessly put “extinction” rather than “no debt due” in a pricing supplement on his way home from school and burned to death.[2]

General limited recourse for investment funds

Where you are facing an investment fund held by equity investors it is slightly — but not very — different. Generally, there is no security, since there’s no question of ring-fencing separate pools of assets. (But investment managers can get in the way and steal options, so be on your guard — see below). Limiting recourse to the fund’s entire pool of assets: A provision which says “once all the fund’s assets are gone, you can’t put it into bankruptcy”, is essentially harmless, seeing as once all the fund’s assets are gone there’s no point putting it into bankruptcy. This is the same place you would be with a single-issue repackaging vehicle: the corporate veil does the work anyway.

===Limiting recourse to assets managed by an agent=== On the other hand, limiting recourse to a pool of assets within a single fund legal entity — say to those managed by a single investment manager (some funds subcontract out management of their portfolios to multiple asset managers) — being a subset of the total number of assets owned by the fund — is a different story altogether. This, by sleepy market convention, has become a standard part of the furniture, but to the JC and his friends and relations, seems batshit insane.

So firstly, the investment manager is an agent. An agent isn’t liable at all for any of its principals’ obligations. It is a mere intermediary: the JC have waxed long and hard enough about that elsewhere; suffice to say the concept of agency is one of those things we feel everyone in financial services should know; this is not one to drop-kick to your legal eagles: it is fundamental to the workings of all finance.

So why would an agent seek to limit its principal’s liability to the particular pool of assets that principal has allocated to that agent?

Limited recourse formulations

The following, rendered in the linguistic mush you can expect from securities lawyers, are the sorts of things you can expect the limited recourse provision to say without material complaint:

- Recourse limited to segregated assets: your recourse against the SPV will be strictly limited to those assets that are ring-fenced for the particular deal you are trading against. This ring-fencing might take the form of:

- Security and limited recourse: security and contract (in an old-style repackaging with a regular LLC) — there there is a subtle trade off between security over your assets (preferring your claim against all other comers) and limitation of that claim to those secured assets; or

- Corporate structure: by means of a specialist corporate structure providing for segregation of the corporate personality into little cells which may[3] or may not[4] have their own legal personality (if the SPV is a segregated portfolio company or an incorporated cell company);

- No set-off or netting between cells: Netting and set-off will be limited to the specific cell you are facing: this means if your deal goes down, others issued from the same SPV can continue unaffected — boo — and vice versa — hooray.

- Extinction (or non-existence) of outstanding debt: Following total exhaustion of all assets after enforcement, appropriation, liquidation and distribution, and realisation of all claims subsequently arising form those assets, your outstanding unpaid debt will be “extinguished”.

- Here the intention is that you will never have legal grounds for seeking judgment, and thereafter commencing bankruptcy proceedings, for that unpaid amount once your own cell is fully unwound and its proceeds distributed.

- Pendantry alert: some sniff at this “extinction” language, fearing it implies that there was once upon a time, until extinction, a debt for an amount which the company was theoretically unable to pay — meaning that the company was, for that anxious moment in time, technically insolvent. These people — some hail from Linklaters — prefer to say “no debt is due” than “the debt shall be extinguished”.

- A proceedings covenant: You must solemnly promise never to set to put the SPV into insolvency proceedings. If you agree to all the foregoing, you should have concluded you have no literal right to do so, so this shouldn’t tax your conscience too greatly.

See also

References

- ↑ The investment manager is. So should she be barred from managing assets? THIS IS NOT THE TIME OR THE PLACE TO DISCUSS.

- ↑ Come to think of it he may have forgotten to file a Slavenburg.

- ↑ such a company and incorporated cell company.

- ↑ Such a company a segregated portfolio company.