Writing for a judge: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|design| | {{a|design| | ||

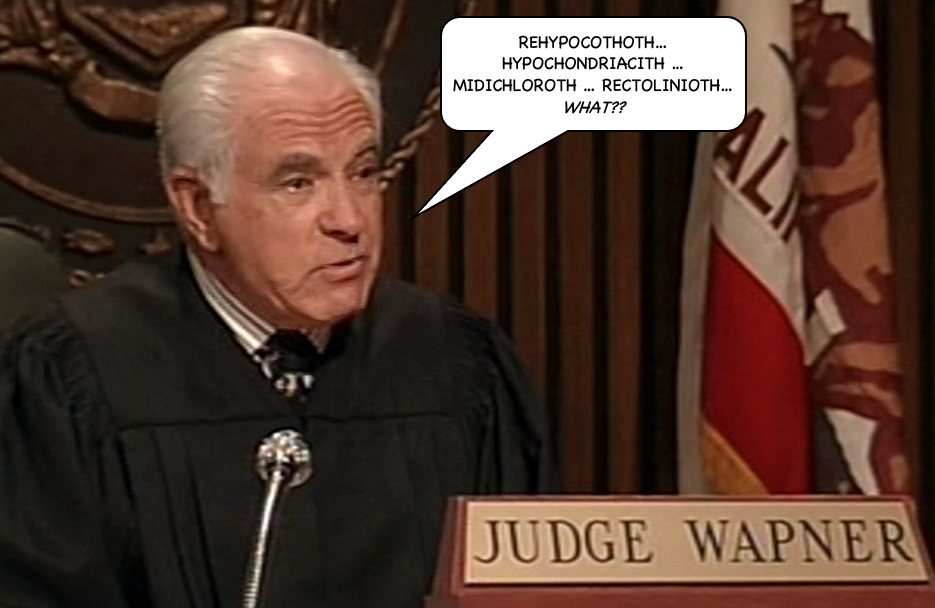

{{Image|Wapner|png|}} | |||

}}No, you are ''not'' writing for a judge. | }}No, you are ''not'' writing for a judge. | ||

Latest revision as of 12:25, 15 October 2023

|

The design of organisations and products

|

No, you are not writing for a judge.

Firstly, and this is no more than a re-articulation of the commercial imperative: you are writing for a record, to avoid dispute and with the firm hope that, from the moment the ink has dried, no human eye will ever behold your contract again. You are not writing to maximise your position, to steal options from an inattentive client, much lass to reserve your position in case of future litigation.

Every lawyer knows the cost of any kind of litigation is out of all proportion with the value of the contract to which it relates. It is never a good outcome to have your contract tested in court, even if you win. Therefore, you are writing to avoid a judge having to read it.

Secondly, and with the greatest of respect to our learned friends on the woolsack, commercial court judges are by no means expert, or even experienced, in complex financial services arrangements. They just don’t see them.

The same cognitive dissonance is involved in seeking a Queen’s Counsel’s opinion on a complex derivatives. What the hell would a QC know about it? Trillions of dollars of derivatives are traded every year, and there are literally thousands of market participants with deep ever day experience of all the permutations, stretching back years, but none of them are QCs, let alone high Court Judges. Market participants have a far deeper, richer, and more sophisticated understanding of the conventions and customs, absurdities, trap-doors, tricks for young players, and commercial and legal expectations of participating institutions than could any judge have.

A judge has no better prospect of understanding even the legal concepts than an engineer, surveyor, accountant, or stevedore. She is no better placed to adjudicate on a financial services transaction than any other passenger on the Clapham omnibus. How could she?

Therefore, we should not be surprised, when judges get financial services decisions wrong. And sometimes they do: Greenclose v National Westminster Bank plc; Citigroup v Brigade Capital Management. To be sure, they are just as likely to get them right, such as Barclays v Unicredit, and this is not to criticise the judiciary, but only to state an undeniable reality. You need to be close to this stuff to understand how it works. It is in no way intuitive. It is hard. Much of it is nonsense.[1] Litigation is, at best, a crapshoot.

So if you design your drafting for the benefit of judges in priority to the men and women who are party to it, you are out of your mind. But for the very same reason, the best means of drafting for a non-specialist judge is exactly to draft for a non-legally qualified client: if it is clear to the counterparties, it will be clear to a judge. But even better than that, if it is clear to the counterparties it will never come before a judge. That is your optimal outcome.

No one litigates an argument that they know they will lose.

See also

- OneNDA

- The quotidian is a utility, not an asset

- Ditch tolerance and ditch proximity

- Ninth law of worker entropy (the “anal paradox”)

References

- ↑ To which this site is reverent testament.