Playbook

|

Negotiation Anatomy™

|

Playbook

/ˈpleɪbʊk/ (n.)

A comprehensive set of guidelines, policies, rules and fall-backs for the legal and credit terms of a contract that you can hand to the itinerant school-leaver from Bucharest to whom you have off-shored your master agreement negotiations.

She will need it because otherwise she won’t have the first clue what do to should customers object, as they certainly will, to the preposterous terms your risk team has insisted go in the first draft of your contracts.

A well-formed playbook ought, therefore, to be like assembly instructions for an Ikea bookshelf.

But Ikea bookshelves do not answer back.

Triage

As far as they go, playbooks speak to the belief that the main risk lies in not following the rules.

They are of a piece with the doctrine of precedent: go, until you run out of road, then stop and appeal to a higher authority. By triaging the onboarding process into “a large, easy, boring bit” — which, in most cases, will be all of it — and “a small, difficult, interesting bit”, playbooks aspire to “solve” that large, easy, boring bit by handing it off to a school-leaver from Bucharest.

Doing large, easy, boring things should not, Q.E.D., need an expensive expert: just someone who is not easily bored, can competently follow instructions and, if she runs out, knows who to ask. She thus tends tilled, tended and fenced land: boundaries have been drawn, tolerances set, parameters fixed, risks codified and processes fully understood.

Thus, you maximise your efficiency when operating within a fully understood environment.

Escalation

So, no playbook will ever say, “if the customer does not agree, do what you think is best.” They will say, “any deviations must be escalated for approval by litigation and/or a Credit officer of at least C3 rank.”

The idea is to set up a positive feedback loop such that, through episodic escalation, the control function can further develop the playbook to keep up with the times and deal with novel situations, the same way the common law courts have done since time immemorial. The playbook is a living document.[1]

In practice, this does not happen because no-one has any time or patience for playbooks.

Example

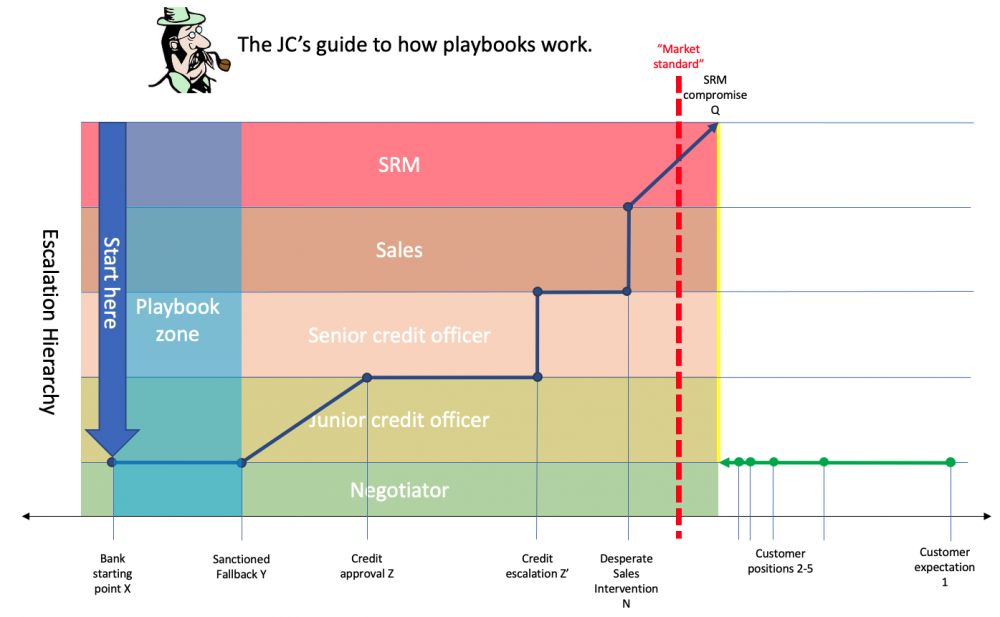

For example, illustrated in the panel above:

- A playbook stipulates starting position X, but allows that if a customer of type B does not agree to X, a satisfactory compromise may be found at Y.

- The playbook “empowers” the negotiator to offer Y — some way yet from any sort of reasonable market standard — without further permission.

- Should customer B not agree to Y, there must be an escalation, to a junior risk officer, who may sanction a further derogation to Z — still unnecessarily conservative, but no longer laugh-out loud preposterous. The negotiator trots back to the customer with Z.

- Should customer not accept Z either, there will follow an extended firefight between risk personnel from either organisation — conducted through their uncomprehending negotiation personnel — taking the negotiation through Z', which will culminate with escalation to sales who might optimistically suggest N, and if that doesn’t do the trick, senior relationship management will be wheeled in, and will cave instantly to the client’s demand to reach a craven surrender at position Q, some way past the market standard and anything remotely necessary or reasonable.

By codifying this process, so the argument goes, not only may we engage materially cheaper negotiation personnel, but we can triage our clients and improve our systems and controls.

But really.

Design and user experience

We have certainly added to our systems and controls; no doubt about that.

But only positions X through Y are codified in the playbook. All those wonderful systems and controls were in play only between X and Y which turned out, quelle surprise, to be a mile behind the front line.

No doubt middle-management can regale its superiors with assorted Gantt charts, dashboards and verdant traffic lights attesting to how well the documentation unit is operating. But all these gears are engaged, and all the systems and controls are running, over the easy, boring bit of the process.

And, at a cost: following this byzantine process to gather this data occupies people and takes time: all negotiations take longer, and none of these gears, rules and triage are engaged at any point where the data might be interesting: the exceptions.

The conundrum: since we know our walk-away position is Z (and, at a push, Q) why are we starting at X? Why is there a fall-back to Y?

Why mechanise an area of the battlefield behind your opponent’s lines, which you know you have no realistic expectation of occupying?

Form and substance

When it comes to it, negotiation snags are either formal or substantive. Formal hitches arise when clients challenge terms they don’t understand. Substantive hitches arise when clients challenge terms they do understand, because they are unreasonable.

Both scenarios are likely; often at once: if, as tends to be the case, people in your own organisation don’t understand your documents, it is a bit rich expecting your clients to.[2]

If your walk away points are genuinely at a point the market will not accept, you do not have a business. Presuming you do have a business, assume any line drawn behind the front line is for pantomime purposes only. It must be a false floor. Allow a little gentle pressure on senior relationship management, and it will turn out to be.

That being the case the answer to formal and substantive hitches lies not in playbooks, systems and controls or organisational heft, but in improving product design and user experience.

Make your documents better. Stop wasting everyone’s time — including your own — with pantomimes.

Simplify

For misunderstood documents, the answer is straightforward, but difficult: simplify them. This is usually not just a matter of language, but logical structure — though simplifying language often illuminates convoluted logical structures too. Pay attention to semantic structure.

And, while financial markets drafting is famously dreadful, emerging technologies can help: run your templates through a GPT-3 engine to simplify them. It won’t be perfect and will make errors, but it is free. Error-checking and quality control is what your SMEs are for. Technology can break the back of an otherwise impossible job.

Remove false floors

If you know you will settle at at least Z, then don’t start X. Your role is to get to agreement as fast as possible. There are no prizes for effort spent in hand-to-hand combat at points X, Y and Z, if you don’t agree until Q. Identify walk away points and start with them.

“But the client needs to feel like it has won something”.

You will hear this a lot, as a self-serving justification for deliberately starting at a place clients won’t like, but there’s little data on it, nor much other reason to believe it is true.

With external advisors there is certainly a pressure to be seen to be doing something — but they tend to be on fixed fees and can equally well market themselves as having already reviewed the standard form and being signed off.

Why deliberately aggravate your clients just to climb down performatively at the first objection? How does that create a better impression (off-market, disorganised, weak) than presenting a clear, coherent and fair document in the first place?

Legaltech as enabler of sloppy thinking

And here is where the great promise to LegalTech stumbles. It offers the capacity to do clerical jobs faster. It opens the door to infinite variability, optionality, within your standard forms. Tech can now accommodate any complications in your standard forms that you can be bothered dreaming up.

“We love automation. We love automating complex things. Our app can handle anything with its structured questions: it can add new clauses, new schedules. The complexity is mind-bending.”

This — a direct quote from a legaltech start-up conference pitch — gets the proposition exactly backward. Embrace complication not because you can, but because you have no other choice. When you are designing user experience for a standardised process you absolutely do have another choice.==See also==

References

- ↑ This rarely happens in practice. Control functions make ad hoc exceptions to the process, do not build them into the playbook as standard rules, meaning that the playbook has a natural sogginess (and therefore inefficiency).

- ↑ Best example is the hypothetical broker dealer valuation terms in a synthetic equity swap. The JC, once responsible for legal coverage of a synthetic equity business, asked what the hell these terms, which were gumming up every single negotiation, were for. No-one knew: all kinds of contradictory hypotheses were offered by tax advisors, compliance and risk officers and operations personnel, but they converged on the simple idea: everyone else in the market has this concept in their docs.