Everyone is fighting a battle you know nothing about

|

Crappy advice you find on LinkedIn™

|

Every girl has her personal problems;

Every boy has character flaws —

But the outlook is fine, since

You don’t care about mine,

And I’m highly dismissive of yours.

- — Dangerboy, The Girl at the Bus Stop.

So we have the old LinkedIn saw:

Everyone is fighting a battle you know nothing about .

If only people would belt up about their goddamn personal problems, every now and then, so this were occasionally true.

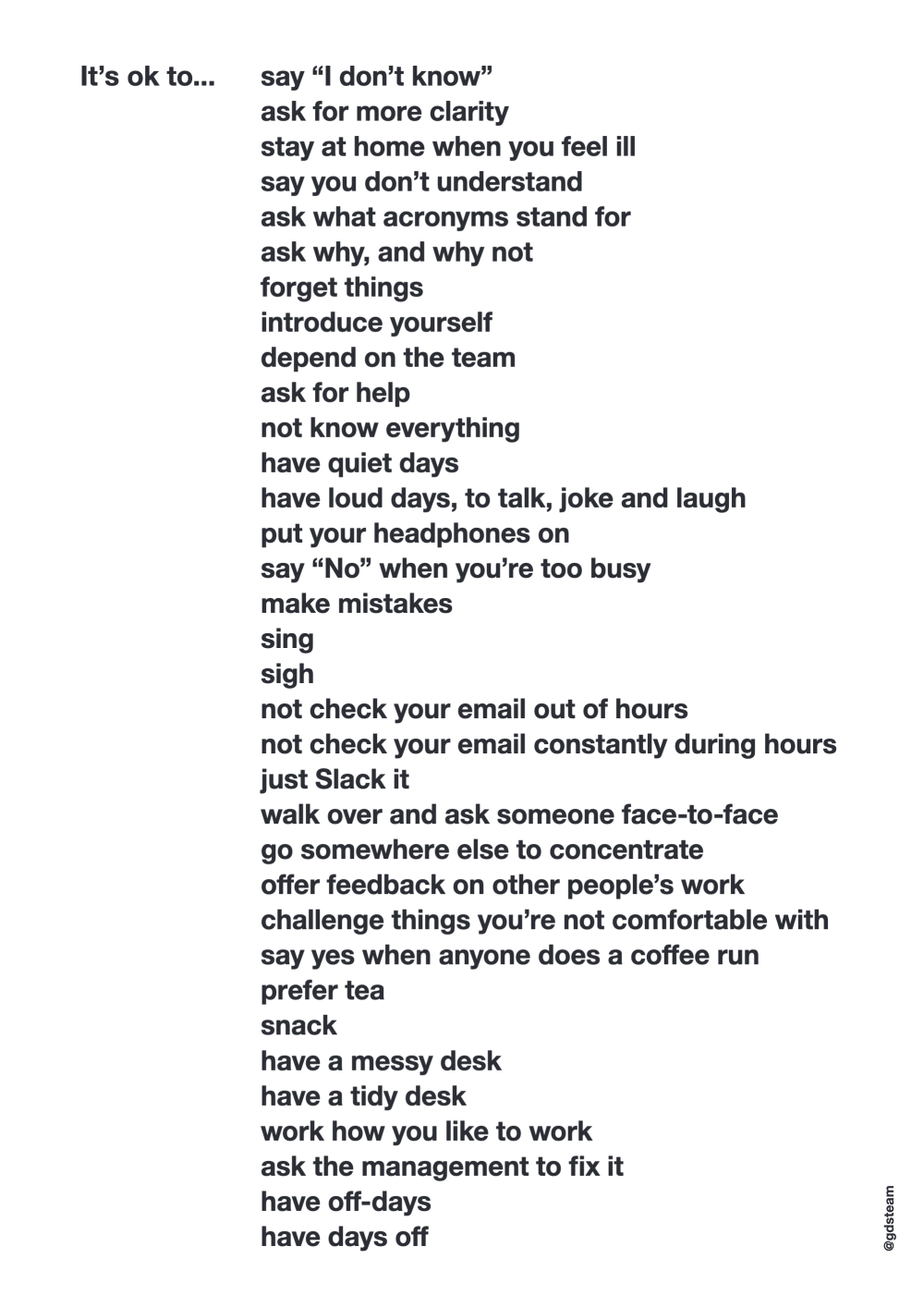

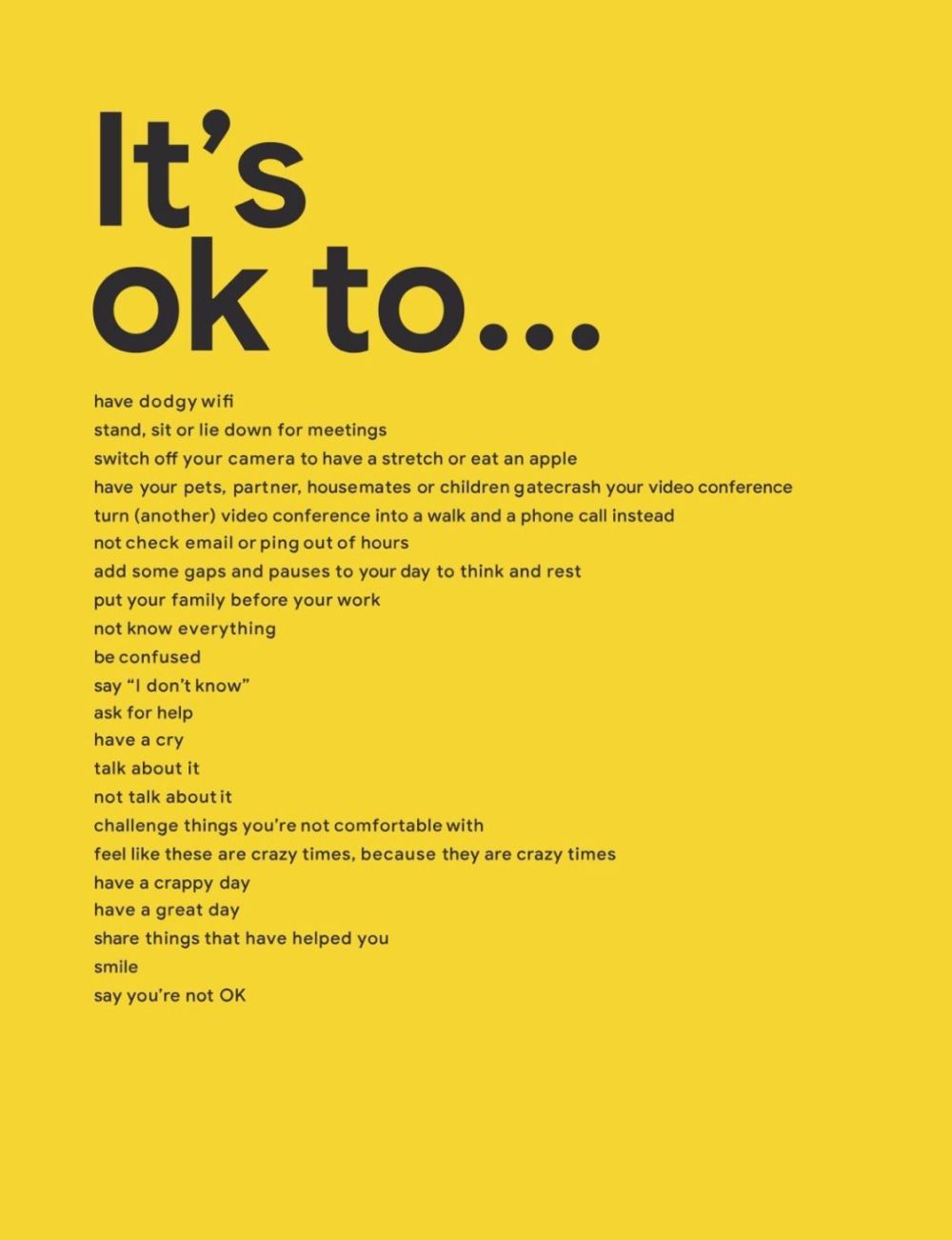

The JC is working up a theory, propelled by exasperation at the prevalence of complaint as a latter-day professional occupation, that the moral crisis that engulfed the 20th century has claimed the opportunity cost. So we can have this kind of dreck from (where else?) the public service, helpfully telling inductees about the absolute lack of any standards of behaviour; a mixture of what ought to be the bleeding obvious — things that should and, frankly, do go without saying in any sentient organisation with aspirations of continuing in business — items that will appeal to work-shy teenagers used to having their parents tidy up after them, and items that ought to be utterly out of the question in any organisation fulfilling a service of any commercial or civil importance to anyone in the community.

Here’s the TL;DR. You are a professional. You get paid an unfeasibly large amount of money. For this money, you are expected to turn up, and perform, every day. You are expected to do a superior job, fast, on time. Leave your chaotic private life at the door. If you can’t, expect to be judged by how you present.

The bleeding obvious

Let’s start with the things which any organisation with a brain should expect from all its staff

- Say “I don’t know”: Once, assuming the thing you don’t know or understand isn’t a basic root function of your present role;

- Ask for more clarity: Assuming you have the gumption, at an early point, to stop bothering everyone and use your own common sense;

- Stay at home when you feel ill: Like, actually, contagiously sick, and not just “having an off-day” — see below. This is called sick leave, has been part of workplace regulation for decades, is not an annual entitlement to be used up, and is hardly in need of a patronising poster to encourage people to use it.

- Turn a videoconference into a phone-call: This is a nice idea. Indeed, you would be doing your organisation an even better service persuading whoever convenes these blessed videoconferences to just stop doing so without substitution, but this is an earnest step in the right direction.

- Not check email out of hours: Okay, but who doesn’t doom-scroll their work inbox every now and then? If you are passingly interested in your organisation and your career, you will: in which case this is bad advice.

- Ask for help: One of the core functions of any collaborative enterprise, so it should not be a surprise that fellow workers might ask each other for assistance every now and then. But there is proactive collaboration, and there is (non-directed) laziness.[1]

- Challenge things you’re not comfortable with: Of course — could a contrarian disagree — but remember serenity’s prayer. If you find it hard to reconcile your organisation’s capitalist objectives to your own neo-Marxist values — and HR’s heroic efforts to accommodate you don’t quite go far enough — consider whether you are really in the right line of work.

Don’t get carried away

- Make mistakes: Well, okay. Everyone makes mistakes. But there are mistakes — snap judgments you are forced to make with limited information when dealing with a novel situation which turn out to be sub-optimal — and there are mistakes — basic errors calling into question your competence to carry out your daily function. The former are fine if you own up to them quickly, learn from them, and don’t repeat them. The latter are not okay. Expect to be disciplined if you cannot carry out your basic function.

- Put your family before your work: Look, look, look: everyone with a brain — well, a heart, at any rate — does this; only a cretin announces it at work. Besides, being a professional means organising your private life so it doesn’t intrude on a reasonable working day. Genuine crises are exceptions: if junior has been rushed to A&E with a javelin through his thigh, no-one expects you to bravely box on at work. But if crises crop up weekly — did the child minder let you down again — then sort your self out. This is your problem, not your employer’s.

- Talk about it/not talk about it: Profound judiciousness is required here. There are some things one absolutely must talk about, and many one absolutely must not. Now by all means talk about problems with the cross-indemnity structure in that new revolving credit facility. For God’s sake do talk about that: that, we have to get right. But the simmering dispute with your neighbour about your communal parking space? Shut the hell up about it. You’re at work. There’s stuff to do. Your personal circumstances are a topic no-one needs, and no-one wants, to know about. Re-make yourself each morning as a Spartan for your employment. Present as a stripped-back, unornamented, machine, comprising only those faculties which will further your organisation’s commercial goals. These will include your social skills, your emotional intelligence, your empathy, all those illegible qualities by which you persuade, build consensus, solve problems, develop relationships and deliver the nuanced, ineffable, superior performance your employer asks of you. These do not, by and large, involve your political views, your fascination with association football or the manifold ways you have been wronged by circumstance. If you are on deck, with a phone, a job, an internet connection and the luxury of cultivate a detailed catalogue of your grievances, you are privileged enough to spare your colleagues the details. Yes, you may be fighting a battle others know nothing about. Part of that battle should be a struggle to keep it that way.

- Not know everything: There’s knowing everything, of course, and then knowing nothing. To be sure: if you are the office apprentice, a basic facility with making tea and deft photocopying is all any one can ask of you, but be a hoover. If, after nine months, tea and xeroxing remain your only qualities, be sure to remember where you put your coat — you may find you need it suddenly. If you have been there, ploughing the same furrow for seven years, then you damn well should know near enough everything there is to know about the BAU. You should be the one people turn to at the moment of tetas arriba, and no-one wants to hear you going, “I don’t know! Don’t ask me!” Earn your paycheck, soldier. Think of something.

- Be confused: Don’t make a habit of being confused. Unavoidable, every now and then, but to be avoided where possible. The bare minimum anyone ought to be able to expect of your years in tertiary education — apparently a vain hope these days — is a basic faculty for the English language and a general ability to reason, think critically, and ask informed questions; all skills calculated to head off confusion in the first place, and dispel it should it arrive unbidden from the moronic actions of another. Your own ongoing confusion is a sure sign that you are, to put not too fine a point on it, useless. Don’t be useless.

Not okay

- Have dodgy wifi: Not okay, at all. In fact, lame. Sort your home office out. If you can’t, go to the actual office.

- Stand, sit or lie down for meetings: Stand if you must — though expect little chicklings to find this a bit aggressive, but if you feel like lying down, — seriously? You want to lie down? — You can always clock-off, go home and do it there, collecting your coat on your way out the door.

- Have your pets, partner, housemates or children gatecrash your video conference: No, just don’t. Close the door. If you don’t have a door, go to the office. You are a professional. You should be mortified if your child invades your Zoom call. And no, filters are not okay either.

- Add some gaps in your day to think and rest: Think, okay; — rest? Look: you’ve been sitting on your chuff all day doing conference calls. What is that if it isn’t rest? Unless we are talking about lunch, and you self-identify as a wimp — do your resting at the end of the day.

- Have a cry: Overcoming the stigma of mental health gets a lot of play, and we are frequently beseeched to be more understanding about each others’ psychological travails — and so we must — but that does not mean living through them at work. If your mental state is vulnerable enough that you are uncontrollably crying, you should not be at work. It is no place to work through existential mental health issues, and nor is not fair on your colleagues — or you, for that matter — to expect them to provide the treatment you may need. If it is your work that is causing your mental issues, and you can’t resolve them, then change your job.

- Feel like these are crazy times, because they are crazy times: No doubt he’s been cancelled by now,[2] but Rudyard Kipling had it right: keep your head while all about you are losing theirs. The craziest thing about 202

12 isthat there hasn’t been a world war in seventy years[Subs: can we think of something else that is crazy about 2022?]. Think yourself lucky, and get on with it, while everyone else is running around with their hair on fire flapping about how crazy it is. - Have a crappy day: See: have a cry. If you take this to mean “I can just be a bit rubbish at work” well, yes you can, but expect to be marked down for it. You are an athlete: do your talking on the pitch. Have a crappy day in your own time.

See also

References

- ↑ Directed laziness is a laudable end, and one that the JC regards one of the highest functions of the working stiff.

- ↑ Can confirm, per the Independent: “Fatima Abid, general secretary of the students’ union, wrote on Twitter: “We removed an imperialist’s work from the walls of our union and replaced them with the words of Maya Angelou.”