Lateral quitter

|

The Human Resources military-industrial complex

|

Lateral quitter

ˈlætərəl ˈkwɪtə (n.)

One who voluntarily leaves your organisation to work somewhere else. A greatly unexamined constituency.

Management will steadfastly deny any lateral quitter is missed. The trend towards “exit interview by chatbot” — if they bother with one at all — suggests corporations systematically undervalue the people that they are losing.

Indeed, HR appears gripped by the conviction that having employees at all is a matter for regret. It makes scant effort to discourage, impede or even identify those who are thinking about leaving, let alone asking those who eventually do for their motivations.

This is an oversight. On the premise that all staff bring some value and, unless your approach to hiring is catastrophic, a good half bring more than they cost, lateral quitting is, broadly, a negative-sum game. That is, a game businesses should try to avoid playing.

Lateral quitters are good staff, QED

Lateral quitters tend to be good employees: ones you didn’t want to leave, who contributed more than they cost. They will be that, at any rate, if your HR capability is functioning passably — Spartan if — because if it is, you will already have dispatched the ones you did want to leave. Right?

Maxim: Professional employment should not be a hostage situation. Either way.

The competence phase transition

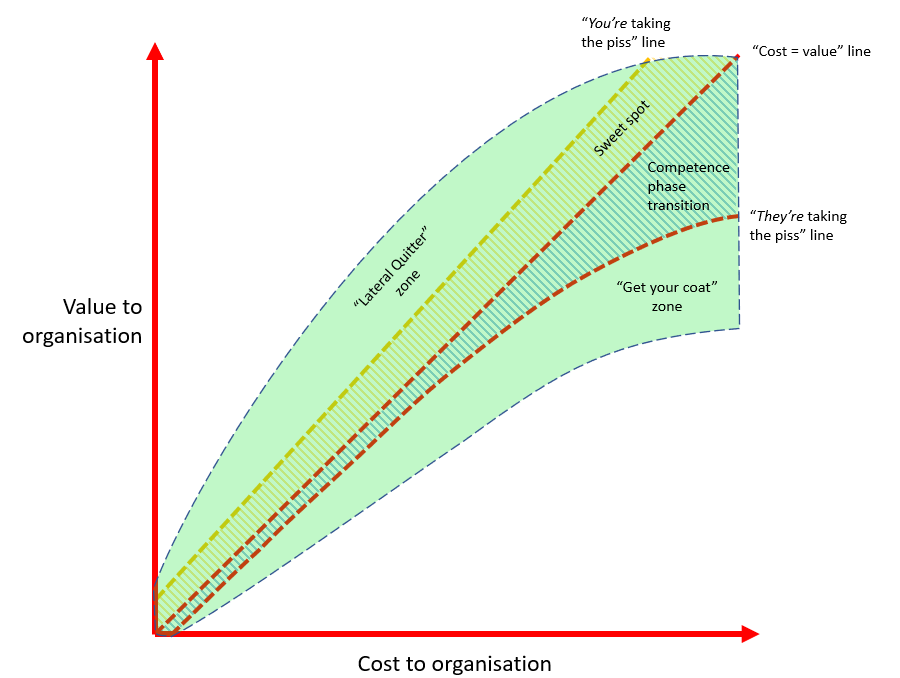

Now, it is true: there is a “bid/ask spread” between staff you genuinely value and those you would be just as happy never to see again.

This we call the “competence phase transition”. It is a sort of purgatorial state, occupied by earnest plodders who don’t really earn their keep but do no real harm, such that you can’t quite summon the bureaucratic energy to whack them, but nor would you shed crocodile tears if they did decide to push off.

The phase transition is a remarkably stable state: staff of tepid bearing can comfortably inhabit it for decades: the JC speaks from happy experience. Every now and then, one may have a rush of blood to the head and throw in the towel — often at times of mass exuberance: you know, dotcom booms, crypto mania, that kind of thing — when in a fit of uncharacteristic madness, they join fly-by-night stablecoin start-ups and legaltech ventures, never to be heard of again until they show up in the fossil record of one of these mass extinctions that the financial service industry undergoes every decade or so.

Godspeed, all our friends in operation roles at Cryptöagle and Lexrifyly right now, by the way: hope it’s as fun as it looks while it lasts.

Mediocrity drift

Anyway. Lateral leavers will tend to be your better employees. Being smart, they are likely to know this and, being proactive and energetic people, likely to do something about it. Those who provide an undervalue, by contrast, are unlikely to do anything about it — if they are smart — and even the dumb ones who try won’t be able to.

There is a negative feedback loop here, therefore. If all people you hire have an equal chance of working out well — their competence is evenly distributed — and those who work out better than expected are more likely to quit and those who disappoint are more likely to stay, over time the competency of the workforce will skew mediocre.

We call this “mediocrity drift”.

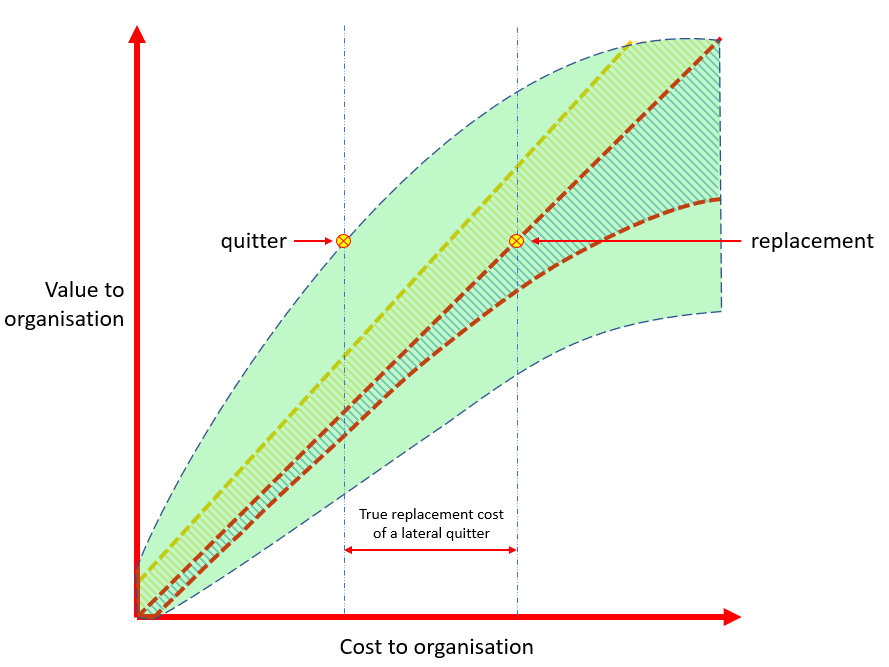

Outperforming quitters will be replaced — at necessarily greater cost, ceteris paribus, because the one and only time you are obliged to mark to market is when you hire — by those having no institutional knowledge, no internal network, and even controlling for that, only an “evens” chance of working out well.

The loyalty discount

“But outperforming employees will be rewarded with better pay and progression” is an objection only offered by someone who has not heard of the loyalty discount.

HR will have ironclad compensation bands, based not on any assessment of individual quality (because how could HR, of all functions, possibly know?) but by some opaque benchmarking operation carried out by consultants “gathering data” from industry peers. However good an individual is, she will be forever pegged within her bands.

Where exactly this data comes from, no-one will know. Assuming the consultants don’t just make it up out of whole cloth, assume it will be volunteered by other HR departments. Now think for a moment, about interests here. If you were the highest payer on the street — therefore having a natural advantage over your peers in the lateral hire market — wouldn’t you want to keep quiet about that? Wouldn’t you be inclined to undercook the data you submitted to benchmark surveys? Would you weed out the lateral quitters who weren’t there at year end?

But come on JC: surely, regulated institutions wouldn’t knowingly skew important market data to suit their own financial interests, would they?

Once they have successfully “benchmarked” their salary bands against this phantom market, HR’s main concern will be not setting a precedent. Your manager will shake his head mournfully and say, “my hands are tied.” There will be overlaid volatility limits: no individual can move more than ~ percentage of last year’s pay. Note the necessary compressing effect these limits will have through time.

Now you might be inclined to look at this and think, well, this is a fine state of affairs. By pruning the truly dismal and letting jumped-up and flighty go, we are nicely containing our costs within a tight range. This is depends on your not needing to replace them.

Indeed, in an organisation big enough to have a human resources department you probably don’t — or at least wouldn’t, if you could hang on to staff who were any good and get rid of the grifters. Parkinson’s law obtains.

But if all you have left are the plodders, do not expect them to take up the slack. You will need a replacement, and — unlike the person who just departed — you must per her her actual value. At this point you have categorically worsened your position.

Look after what you have

How to stop this? Well, for one thing, focus your attention on your employees who deserve it: the good performers.

Try to stop them leaving. Do this by figuring out why they are leaving. There may be complicated sociological explanations, but for most places it will take no towering intellectual insight to figure it out. In broad strokes it boils down to: money, progression, and quality of work.

Another way of looking at that continuum is this: you pay poor employees more than they are worth to you, and good employees, less than than they are worth, expect to have crappy employees.