Sub-custodian

|

Prime Brokerage Anatomy™

|

A sub-custodian is a sub-contractor appointed by a main custodian as part of its custody network, to hold client assets on behalf of a main custodian — usually to carry out functions that the main custodian can’t. for example, to hold assets in a jurisdiction where the main custodian has no licence to do so.

A sub-custodian therefore doesn’t have a direct contractual relationship with the client.[1]

Subcustodian risk

Custodians and depositaries will try to disclaim all risks of the failure of their custody network, as indeed they will try to disclaim all other risks, real and phantasmagorical. Be watchful of this.

Custody risks ought to be fairly minimal: Unless the sub-custodian is in a weird jurisdiction[2], it should never take beneficial title to the assets it holds, and should have segregated them from its own assets, therefore beyond the putative reach of its ordinary creditors — so the assets remain the client’s at all times — so they should return to the client even on the custodian’s insolvency. It follows that, if client assets are not where they are meant to be on a custodian’s insolvency, there must have been some kind of operational mismanagement, negligence or fraud on the custodian’s behalf (and its insolvency). Since the operating cause of the loss is the mismanagement, not the insolvency itself, any capital charge should reflect operational risk and not credit risk.

None of this will stop custodians invoking the “Lehman” horcrux, of course.

Now if a sub-custodian profoundly breaches its custody obligations — which it owes to the main custodian, of course — should that custodian be able to pass its loss back to its innocent client?

It will say “yes” — of course it will — but to what degree has it been complicit in its delegate’s failure? Was it properly monitoring the sub-custodian’s performance? Was it duly diligent in appointing it? The custodian will wail, chomp and complain that it can’t be expected to price flakiness of unaffiliated third parties in far-flung locales into its business offering. Fair, perhaps — but then it did hold itself out as being in some way competent in the safe-keeping of customer assets didn’t it? Wouldn’t that include being diligent in monitoring the performance and capabilities of its custody network?[3] After all the custodian is usually a sophisticated global multinational with experience managing sub-custodians in far-flung locales and it does have contractual privity with them.[4]

The one place it makes some sense is in one of those weird jurisdictions where, by law or market convention, one cannot isolate custody assets from a local custodian’s insolvency. There, it is fair for the client to bear that risk (as it is the client’s choice to take on that “country” risk, and the main custodian cannot avoid it however prudent or diligent it is).

In most jurisdictions, exposure to a custodian for the return of client assets is not a solvency risk as such, seeing as the custodian should not beneficially own client assets and should have segregated them from its own assets, therefore beyond the putative reach of its ordinary creditors. It follows that, if client assets are not where they are meant to be on a custodian’s insolvency, there must have been some kind of operational mismanagement, negligence or fraud on the custodian’s behalf (and its insolvency). Since the operating cause of the loss is the mismanagement, not the insolvency itself, any capital charge should reflect operational risk and not credit risk.

Delegate versus sub-custodian

Be warned: There are people more learned in the ways of the world than your correspondent who do not share this view. Let’s call it a dissenting judgment therefore. Or a piece of contrarianism. But it’s a cracker.

The difference betwixt

Delegation, according to a natural definition, means “to entrust (a task or responsibility) to another person, typically one who is less senior than oneself.”[5] So:

- Dear Sir/Madam: Let me introduce you to my glamorous assistant, Igor, who will carry out this work for you under my supervision. while your day-to-day interaction will be with Igor, I remain your loyal servant, and shall be answerable to you for Igor’s timely and competent performance.

Being delegated a custody function — agreeing to act, as AIFMD puts it, “at the first level of a custody chain”, as the direct custodian to a fund on behalf of the depositary whom the fund has appointed to carry out that function is, in this old fool’s view, not the same being the depositary’s sub-custodian. It is really quite different:

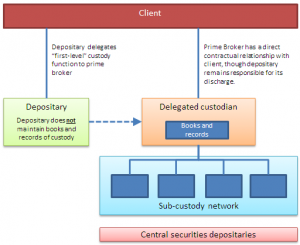

- Delegate: A depositary who delegates its custody function steps out of the custody chain. It won’t hold the client’s assets at all. It will instead pass that responsibility to the delegate — usually, a prime broker with designs on a spot of rehypothecation. The delegate will record the end-client’s interests in the custody assets directly in its own books and records — that is, the delegate itself, and not the depositary, will be “at the first level of the custody chain”.

- True; the delegate may have to report everything it does to the depositary, but the delegate’s record, not the depositary’s will be the “golden source” record of the safekeeping client’s assets. The depository might copy the delegate’s report, but the delegate’s books will be what count.

- Note that a custody delegate can see the ultimate client and, should it have lent money to that end client, it has enough control over that client’s assets to (i) take security over them, and (ii) defray its financing costs by rehypothecating them. For someone in the business of margin lending — say, a prime broker — these are pretty fundamental abilities, so expect prime brokers to be very enthusiastic about being delegated a depositary’s safekeeping function. They will be a lot less keen on being the depositary’s sub custodian, on the other hand.

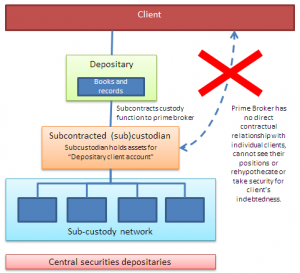

- Subcustodian: A subcustodian, by contrast, stands behind the “first level” custodian. The ultimate client cannot (directly) see it, and it cannot see the ultimate client. A sub-custodian holds the custodian’s client assets in a single omnibus account, in the custodian’s name but marked as “client assets” and therefore unavailable for the main custodian’s creditors. If the main custodian were not obliged to tell you about its sub-custodians, you would not even know they were there. A sub-custodian holds assets for the main custodian, only sees the main custodian, and won’t know who its individual clients even are, let alone which assets it holds for the main custodian belong to which clients, much less have a direct interpersonal or contractual relationship with those clients. Since it doesn’t know to whom they belong, a sub-custodian won’t be in a position to take security over or rehypothecate any assets it holds[6] — hence it ought to be happy enough signing a no lien letter.

Careful though: Both CASS and AIFMD/UCITS are a little sloppy in their use of the word “delegation”, using it on occasion to mean something that is probably meant to refer to a subcontracting arrangement[7]. CASS only really talks about subcontracts, though AIFMD and UCITS deal with true delegation and subcontracts.

Why delegate?

Why do depositaries delegate their custody functions under AIFMD and UCITS then? Market structure is why.

- AIFs and UCITS funds are required to have a local depositary to look after the fund’s interests, make sure it is properly managed, and to look after its assets. The depositary must be independent and must avoid conflicts of interest with the fund, such as would arise if the depositary lent to or traded with the fund. A depositary typically cannot act as a prime broker (a bank who lends on margin to hedge funds).

- Funds — particularly hedge funds and AIFs, but sometimes UCITS too — like to invest “on margin”, borrowing funds from a prime broker against the security of the assets it purchases with the margin loans.

- Prime brokers like to have assets to it can use them, defray its funding costs and manage its balance sheet.

- Structural problem therefore: Depositary is meant to hold the assets, but it can't lend against them. PB wants to lend against assets, but the depositary is meant to hold them.

- “Hold on,” says the PB. “If the depositary holds the assets, then I can hardly rehypothecate them, can I, and we know how important rehypothecation is to my business model, don’t we?”

- The depositary shrugs. “So, I'll make you my sub-custodian,” he says, “There: rehypothecate to your heart’s content.”

- “No can do,” says the PB. “I can only rehypothecate against indebtedness, and you, dear depositary, don't owe me anything. Only the fund does. And besides, as a sub-custodian I only see an omnibus account. I don't know who owns what inside it. For rehypo to work, I have to have a direct contractual relationship with the fund. That’s the deal.”

- Answer: the depositary delegates the custody function to the prime broker. Both AIFMD[8] and UCITS[9] allow this in certain circumstances, but there are complicated rules as to whether the depositary can shift responsibility to the PB.

No lien letters

CASS 6 has a requirement that subcustodians provide a no lien letter to confirm they are not taking security of retaining any other rights over custody assets other than customary liens and charges as security for their ordinary fees and expenses.

These customary charges include the subcustodian's fees for holding assets and incidental expenses arising from its safe custody, but do not include liabilities arising from margin finance or other transactions between the subcustodian and the end client.

This is because, between an end client and a subcustodian, there should be none. A subcustodian will generally hold assets in an omnibus account in the name of the main custodian (but for its clients), therefore will not know the identity of the end clients, much less have a relationship with them, and therefore should not have any direct liabilities against them (at least that have anything to do with the subcustodian relationship).

This is in contrast to the main custodian, who necessarily knows who the individual clients are and, if it is a prime broker, is likely to have lent money to individual end clients to purchase those specific securities, and a term of that finance will be that the client grants security over the assets in question, as well as possession (hence they are held in custody) and rights of reuse. Because it will have individual custody records the prime broker as a head custodian will be able to take security directly over an individual's securities within its books and records, and not over the whole omnibus pool.

See also

References

- ↑ Compare with a delegate, who carries out the main custodian’s client-facing function on its behalf, as described below.

- ↑ Being one where by law or market convention one cannot isolate custody assets from the bankruptcy of the local custodian.

- ↑ A diligence standard that, for Europeans, is enshrined in AIFMR (Delegated Regulation DR20) and UCITS (Article 22a2(c)).

- ↑ Yet another argument, wonders this old contrarian, for tactical deployment of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999?

- ↑ let me Google that for you

- ↑ Except to cover its own direct custody costs.

- ↑ See, for example CASS 6.3.4, and the flush text after AIFMD Article 21(11)(d).

- ↑ Art 21(11) AIFMD.

- ↑ Art 22a UCITS V.