Many-faced heroes, blockbusters and the Long Tail: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) (Created page with "{{freeessay|systems|heroes and the long tail}}") |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{freeessay|systems|heroes and the long tail}} | {{freeessay|systems|heroes and the long tail|{{pn}}}} | ||

{{nld}} | |||

Latest revision as of 07:50, 26 July 2024

|

The JC’s amateur guide to systems theory™

The Jolly Contrarian holds forth™

Resources and Navigation

|

Data, managing to margin and blindness to the adjacent possibility

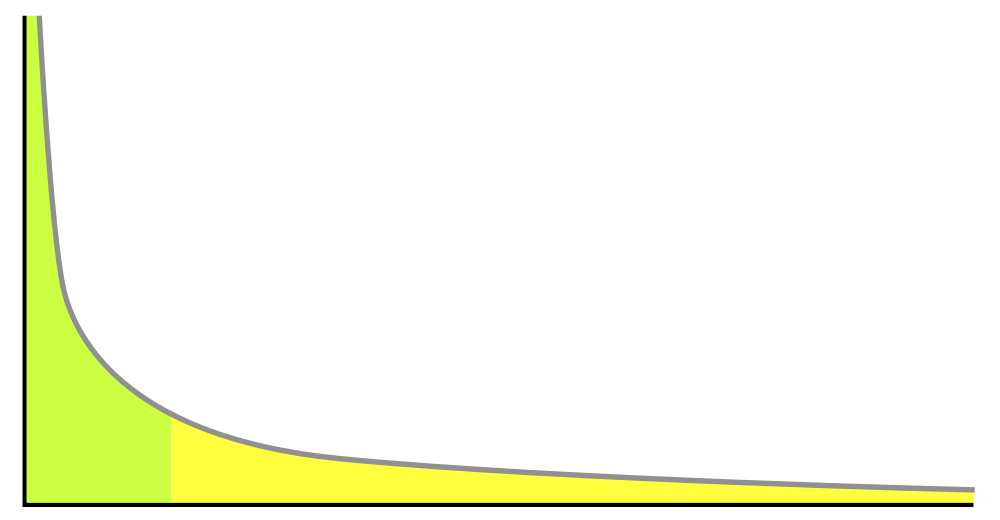

Chris Anderson wrote a book called The Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand about the unlimited potential the internet gives us to mix, match, intersect and explore all the varieties of human cultural experience. Anderson predicted a glorious, multi-hued future where a hitherto unexplored long tail of human cultural experience would unroll itself, offering an unlimited digital commons for every niche interest and cultural proclivity. That is probably happening, but it is on the Dark Web.

But Anderson’s goose was already cooked. Some 30 years earlier — well before the internet — a little-known Californian filmmaker stumbled across a book by an obscure anthropologist that would change everything, and not in the way Anderson would later anticipate.

The book was Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces and the filmmaker — not obscure for much longer — was George Lucas.

Campbell proposed that all myths and stories follow a similar underlying structure, which he called the “Hero’s Journey” in which, after a coy refusal, the protagonist is pulled reluctantly from her ordinary world and into a new realm of adventure where she undergoes trials and challenges and, after a setback overcomes her greatest challenge, gains wisdom or power, and returns home transformed, bringing benefits to her community. There is a standard cast of characters including the hero, a herald, a wise mentor, a villain, a damsel in distress, some loyal retainers and a trickster who seems to be out for himself, in doing so may or may not be helping the hero (but usually turns out to have a heart of gold) and of course the villain.

Campbell spent decades studying myths, folklore, and religions around the world — studying Greek, Norse, Celtic, Indian, African, Native American and Polynesian myths, and argued that the same core elements in these diverse traditions suggested a universal pattern in human storytelling.

Lucas’ hunch that this might be a good model for his screenplays paid off, and others soon cottoned on.

The Star Wars franchise ushered in the era of the modern “blockbuster”. Countless subsequent films — and film franchises — from The Matrix to The Hunger Games to Harry Potter to Superman, Batman, Superman v. Batman and in fact the whole goddamn Marvel Universe have used Campbell’s monomyth.

The effect was profound enough for economist Anita Elberse to write a fascinating yet strangely penetrating book about the modern tendency to plump for the blockbuster over a diverse spread of alternatives.

Collection of related symptoms here, then:

- the necessary historicity of data

- The blockbuster effect

- The invisibility of the informal and betweenness