Stock loan: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|gmsla|}}A strange beast. Actually a type of financing transaction, though it is clothed it the language of [[buy]] and [[sell]]. | {{a|gmsla| | ||

[[File:PB stock loans.png|450px|frameless|center]] | |||

}}A strange beast. Actually a type of financing transaction, though it is clothed it the language of [[buy]] and [[sell]]. | |||

{{securities lending capsule}} | {{securities lending capsule}} | ||

| Line 19: | Line 21: | ||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[Prime brokerage transactions]] | |||

*[[Master agreement genealogy]] | *[[Master agreement genealogy]] | ||

*[[Stock lending]] | *[[Stock lending]] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:50, 7 November 2021

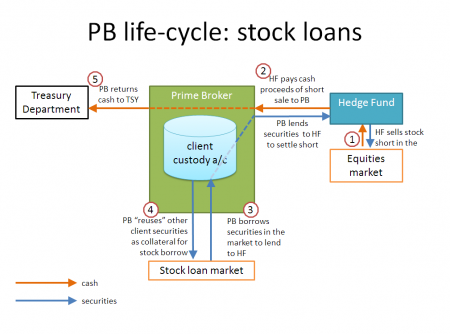

A strange beast. Actually a type of financing transaction, though it is clothed it the language of buy and sell.

Under a securities loan or stock loan,[1] a “lender” transfers securities to a “borrower” in return for the borrower’s promise to return equivalent securities to the lender in the future.[2] In return, the borrower provides agreed collateral to the lender equal to the value of the borrowed securities. If the value of the borrowed securities rises, the borrower must provide more collateral (and if it falls, the borrower may ask for some of the collateral back). The lender keeps market exposure to the borrowed securities at all times: the borrower only has to return what it has borrowed, even if it has fallen in value. Therefore, stock loans are used to short-sell securities.

Why?

Start out with what it is for. Let’s say a well-meaning hedge fund wants to bet against the price of a security. It does that by “short selling”. The key economic feature of a short sale is that you sell a security you don’t own in the first place. If you own it and sell it — well, that’s just a sale.

How do you short sell a security, then? By borrowing it. Borrowing in a manner of speaking. This is where the 2010 GMSLA comes in. It is the master contract under which short sellers borrow securities so they can short sell them.

But hold on. Can you sell something you only borrowed from someone? Nemo dat quod non habet, right?

Well yes, but no. Now in the financial markets, all cats are grey in the dark. Thanks to the principle of fungibility, one stock is the same as another, so the guy who lends you a security doesn’t really care what you do with it, as long as you find an identical one to give back to when he wants it back.

Therefore the 2010 GMSLA is a title transfer arrangement, and not really a loan at all. Clause 2.3 (see panel) clears this up. The Lender title-transfers the security, but at the end of the Loan, the Borrower has to title transfer one back. In the mean time the Borrower is free to sell the security it has borrowed. It is now short the security, in that it doesn’t own the security, but it still has an obligation to go out an buy the security to return it to its Lender and close out the stock loan.

Therefore the stock loan itself isn’t a market transaction. No one goes on risk to the stock by entering into a stock loan. the Borrower goes on risk by subsequently selling the stock it has borrowed.

Does a stock loan count as borrowed money?

According to Simon Firth on derivatives, no. Nor does a repo.

See also

References

- ↑ in EU speak, “securities or commodities lending and securities or commodities borrowing”. Elegant, huh?

- ↑ It may be at an agreed date, or on the lender’s request, or at the borrower’s option.