Emission allowances: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) Created page with "{{a|commodities|}}{{Commodity regulation}}" |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{a|commodities|}}{{Commodity regulation}} | {{a|commodities| | ||

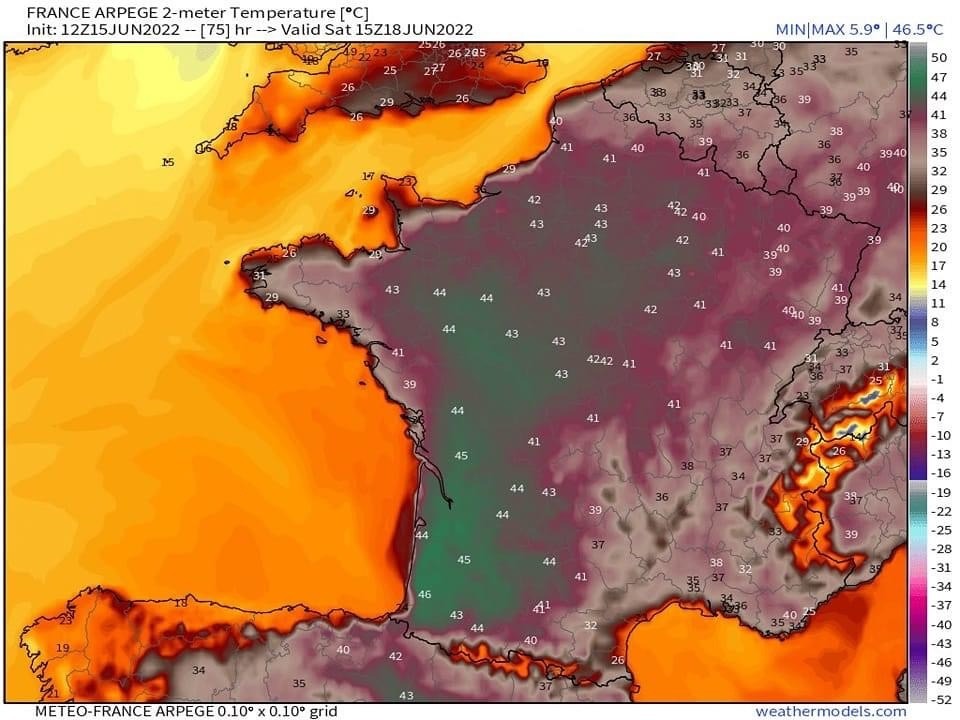

{{image|Hot France|jpg|Bordeaux vintage of ’22 not looking so good.}}}}{{d|Emission allowances|/ɪˈmɪʃən əˈlaʊənsɪz/|n|}} | |||

An opportunity for regulatory arbitrage, created out of thin, hot air.<ref>Boom boom.</ref> Notwithstanding their close connection with the commodities markets, emission allowances are not commodities, but rather a sort of play on global energy policy. In an odd way they resemble [[crypto]], in that they are fully dependent on a collective belief (amongst the world’s governments) that climate change can, and indeed needs to, be managed by imposing financial incentives on the generation (or consumption) of carbon dioxide. [[Emission allowance]]s themselves formally resemble financial instruments, though their custody and legal form are rather unique, and lawyers will get exercised about how one effectively takes security over them. You can’t for example, in Holland. | |||

== A unique asset class == | |||

The [[Emission allowances|emissions allowance]] is a fascinating, transgressive product. It challenges the traditional boundaries in finance. It is neither [[debt]] nor [[equity]], and has none of the qualities of either: it confers no [[ownership]], there is no [[credit exposure]], and at least in some jurisdictions allowances cannot be [[pledge|pledged]] or held in [[trust]], so they acquire the [[credit exposure]] of whomever you find to hold them on your behalf. In some ways they behave rather like a [[cash]] instrument: they represent an abstract value whilst having no intrinsic worth, can only be held, not owned, but unlike cash they expire, and before expiry can be redeemed — not for money, but for the release from an obligation to pay money. | |||

==== [[Regulatory derivative|Regulatory derivatives]]? ==== | |||

Emissions allowance trading schemes are a bit “[[King Cnut|Cnutish]]” in that they are a creature of unilateral government decree: the regulators declared that carbon polluters must submit these allowances, and so they did. In this way you can regard emissions trading as a form of pure, unadulterated regulatory derivative. | |||

As [[Financial instrument|financial instruments]], emissions allowances are unusually susceptible to ''further'' government decree, which may at any time change their terms or eligibility for surrender, or abolish them altogether, as governments of different stripes wax and wane on how they feel about the environment. This is a lot less likely to happen to [[Debt security|bonds]] or [[Equity securities|stocks]]. The risk increases the further into the future you look, meaning that the emissions market tends to trade over a short time-horizon of no more than a year or two. On the other hand, the forward curve is pretty steep, making it an attractive product to finance if you know how. | |||

====Redemption ==== | |||

{{redemption of emissions allowances}} | |||

== Documentation == | |||

==== Fraud, theft and tax ==== | |||

In its formative years the emissions market was also oddly vulnerable to [[fraud]], theft and tax evasion — structural shortcomings that have long since been fixed — but there are a number of decidedly counter-intuitive features and disruption events in the documentation which probably have little use these days. Legal documentation dwells at length on the risks of theft of allowances from custody, in a way it tends not to when bonds and stocks are held in [[custody]]. This should subside over time. | |||

==== “And [[Then I woke up and it was all a dream|then I woke up and it was all just a dream]]” ==== | |||

All of the documentation standards feature a seldom-seen economic close-out feature — present but never used in the 1992 ISDA master agreement, and never seen since — the “[[then I woke up and it was all a dream]]” [[close-out]] scenario, where if there is an incurable disruption scenario, at some point everyone just pretends the trade never happened and walks away. One needs to be careful when financing using the standard documentation suites, therefore. | |||

==Regulation== | |||

====Their relationship with European regulation. It’s complicated.==== | |||

{{Commodity regulation}} | |||

{{de minimis threshold capsule}} | |||

{{sa}} | |||

*[[De minimis threshold test]] | |||

{{c|Emissions}} | |||

{{ref}} | |||

Latest revision as of 19:22, 25 September 2023

|

Commodities and emissions anatomy™

A handy guide to real-world stuff you can eat, burn, or virtue-signal about.

|

Emission allowances

/ɪˈmɪʃən əˈlaʊənsɪz/ (n.)

An opportunity for regulatory arbitrage, created out of thin, hot air.[1] Notwithstanding their close connection with the commodities markets, emission allowances are not commodities, but rather a sort of play on global energy policy. In an odd way they resemble crypto, in that they are fully dependent on a collective belief (amongst the world’s governments) that climate change can, and indeed needs to, be managed by imposing financial incentives on the generation (or consumption) of carbon dioxide. Emission allowances themselves formally resemble financial instruments, though their custody and legal form are rather unique, and lawyers will get exercised about how one effectively takes security over them. You can’t for example, in Holland.

A unique asset class

The emissions allowance is a fascinating, transgressive product. It challenges the traditional boundaries in finance. It is neither debt nor equity, and has none of the qualities of either: it confers no ownership, there is no credit exposure, and at least in some jurisdictions allowances cannot be pledged or held in trust, so they acquire the credit exposure of whomever you find to hold them on your behalf. In some ways they behave rather like a cash instrument: they represent an abstract value whilst having no intrinsic worth, can only be held, not owned, but unlike cash they expire, and before expiry can be redeemed — not for money, but for the release from an obligation to pay money.

Regulatory derivatives?

Emissions allowance trading schemes are a bit “Cnutish” in that they are a creature of unilateral government decree: the regulators declared that carbon polluters must submit these allowances, and so they did. In this way you can regard emissions trading as a form of pure, unadulterated regulatory derivative.

As financial instruments, emissions allowances are unusually susceptible to further government decree, which may at any time change their terms or eligibility for surrender, or abolish them altogether, as governments of different stripes wax and wane on how they feel about the environment. This is a lot less likely to happen to bonds or stocks. The risk increases the further into the future you look, meaning that the emissions market tends to trade over a short time-horizon of no more than a year or two. On the other hand, the forward curve is pretty steep, making it an attractive product to finance if you know how.

Redemption

Emissions allowances are funny things in that they are redeemed against discharge of an obligation to pay the penalty that arises if you discharge carbon and don’t redeem them, but that penalty is oddly never payable as long as you do redeem them. There is some weird ontological cart-and-horse magic going on here, so it is best not to think to hard about it.

Documentation

Fraud, theft and tax

In its formative years the emissions market was also oddly vulnerable to fraud, theft and tax evasion — structural shortcomings that have long since been fixed — but there are a number of decidedly counter-intuitive features and disruption events in the documentation which probably have little use these days. Legal documentation dwells at length on the risks of theft of allowances from custody, in a way it tends not to when bonds and stocks are held in custody. This should subside over time.

“And then I woke up and it was all just a dream”

All of the documentation standards feature a seldom-seen economic close-out feature — present but never used in the 1992 ISDA master agreement, and never seen since — the “then I woke up and it was all a dream” close-out scenario, where if there is an incurable disruption scenario, at some point everyone just pretends the trade never happened and walks away. One needs to be careful when financing using the standard documentation suites, therefore.

Regulation

Their relationship with European regulation. It’s complicated.

You must have a taste for multi-dimensional chess if you want to understand what is required in the world of commodities, freight, weather derivatives and emission allowances. To wit:

Section C of Annex I to MiFID includes the following emissions and commodity products as within the scope for financial instruments:

(4) options, futures, swaps, forwards and any other derivative contracts relating to securities, currencies, interest rates or yields, emission allowances or other derivatives instruments, financial indices or financial measures which may be settled physically or in cash;

(5) options, futures, swaps, forwards and any other derivative contracts relating to commodities that must be settled in cash or may be settled in cash at the option of one of the parties other than by reason of default or other termination event;

(6) options, futures, swaps, forwards and any other derivative contracts relating to commodities that can be physically settled provided that they are traded on a regulated market, a MTF, or an OTF, except for wholesale energy products traded on an OTF that must be physically settled;

(7) options, futures, swaps, forwards and any other derivative contracts relating to commodities, that can be physically settled not otherwise mentioned in point 6 of this Section and not being for commercial purposes, which have the characteristics of other derivative financial instruments;

In scope

- Actual emission allowances, resembling as they do abstract financial instruments — and actually listed as such in Section C of Annex III of MiFID 2 (see point 11! they just snuck in there!) are in scope.

- Emission allowances derivatives, whether physically- or cash-settled, are in scope.

- Cash-settled commodity derivatives — including ones where either party has an option to cash-settle — are in scope.

- Weather derivatives, freight, inflation and economic indicator derivatives that can be cash-settled (it would be kind of fun having physically-settled weather derivatives wouldn’t it) are in scope.

Out of... In scope

- Physically-settled commodity derivatives which (per below) would otherwise be out of scope, if not used “for commercial purposes” and having “the characteristics of derivative financial instruments” are in scope. That one had you going didn’t it!

Really out of scope

- Actual commodities, being consumable, perishable, paint ’em yellow ’n’ pass ’em off as copper, real-world things that people actually need to live, are out of scope.

- Physically-settled commodity derivatives (not falling into the no-man’s land bucket above) are out of scope ...

- ... unless they are traded on an EU trading venue, (i.e, OTC physically-settled commodity derivatives) in which case they are in scope ...

- ... unless they are “wholesale energy products traded on an OTF that must be physically settled” — which case they are out of scope again. I DON’T MAKE THE RULES FOLKS.

There is some angst around weather (inadvertently or on purpose) end-users buying emissions allowances or in-scope commodity derivatives for their own purposes might be required to be authorised under MiFID 2 due to the revised definition of dealing on own account. After some scrambling around, ESMA derived a de minimis threshold test, meaning to keep those who weren’t executing customer orders and whose net exposure was under three billion annually, out of scope.

The definition of net exposure was perhaps too hastily drawn up, as it appears to reference only instruments that would be in scope for MiFID, and even then is a bit slapdash about it — commodities have a complicated relationship with MiFID, and it doesn’t make for casual cross reference — but logically it shouldn’t matter whether a contract is in or out of scope for MiFID, as long as it operates to reduce net exposure.

See also

References

- ↑ Boom boom.