Financial contract: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{A|negotiation| | ||

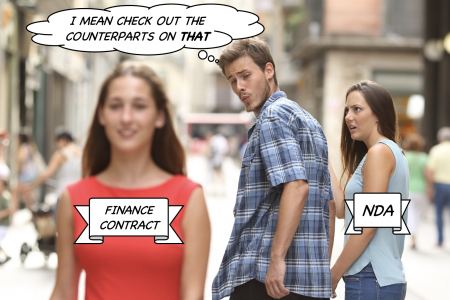

[[File:Bank contract envy.png|450px|thumb|center|Some finance contract envy, yesterday.]] | |||

}}{{d|Finance contract|/faɪˈnæns/ /ˈkɒntrækt/|n|}} | |||

Any [[contract]] the gist of which is for its parties to exchange ''large'' — like, ''really'' large — amounts of [[money]], or [[Securities|money-like things]], having readily realisable value, and the performance of which therefore generates significant [[credit risk]], should one of the parties [[Insolvency|blow up]] before it can pay everything it owes under the contract. | Any [[contract]] the gist of which is for its parties to exchange ''large'' — like, ''really'' large — amounts of [[money]], or [[Securities|money-like things]], having readily realisable value, and the performance of which therefore generates significant [[credit risk]], should one of the parties [[Insolvency|blow up]] before it can pay everything it owes under the contract. | ||

Revision as of 16:40, 27 July 2021

|

Negotiation Anatomy™

|

Finance contract

/faɪˈnæns/ /ˈkɒntrækt/ (n.)

Any contract the gist of which is for its parties to exchange large — like, really large — amounts of money, or money-like things, having readily realisable value, and the performance of which therefore generates significant credit risk, should one of the parties blow up before it can pay everything it owes under the contract.

The classic finance contract is a loan. I lend you a large sum of money; you pay me interest, and eventually pay it back. In the mean time I am constantly beset by daemons, plagues, dread terrors and so on, fantastical threnodies all on the single worry that you never pay me back.

Other good examples are swaps, futures, securities, securities financing arrangements, options, trade financing arrangements, securitisations and commodity supply contracts, and assurances offered to support others’ obligations under loans, like guarantees. Extra points for excitement if they cross borders or constitute, as they often will, regulated activity of some kind.

Finance contracts create special, large, monetary risks. These are different in quality and nature than risks presented by other contracts. You may — in fact, almost certainly will — feel a deep resentment and disappointment at those you engage to carry out your loft extension, as the fourteenth month passes of a project you were assured would take six weeks, but the answer is just to not pay for things they haven’t done, or have done half-heartedly, or have bished up. These things may well exasperate you, mightily, but they aren’t that likely to send you to the brink of ruin, and — trust me — however dismal your contractors may be, suing them will be worse, and “self-help” isn’t really an option. If it was, no-one would hire builders in the first place. Wouldn’t that be a beautiful world.

But enough about the JC’s forlorn endeavours with home improvement. When your business is handing over large quantities of liquid assets to people you don’t know well, in the expectation of they will return them later, things can quickly, and effortlessly, badly go wrong. Therefore, finance contracts have lots and lots of boilerplate aimed to keep those who are owed money-like things safe.

Finance boilerplate is thus an unfortunate, miserable fact of life for banking legal eagles, but we address our labours with fortitude, good humour, and do our level best to see the funny side of it, seeing as we have no choice. Levity is not easy, but possible — it propels this wiki, after all.

But other, non-banking, legal eagles should not have to toil so. One would think they would rejoice in such a freedom from the tedium of financial wordwrightery.

“Look at us,” you might expect they would say, taunting the poor, Promethean banking legal eagle, chained to a rock and pecking away at his own liver, “with our our neat, elegant and stylish prose contracts. How ghastly it must be to be a banking legal eagle.”

But, friends, they do not say that. Many even confect a kind of banking envy. It seems they want their contracts to be long and impenetrable and tiresome, too, to give them that banky cachet. And to do that they have just culturally appropriated banking boilerplate.

And so we find non financing contracts — things like service agreements, employment contracts, licensing arrangements — which should be a model of Ellroyesque brevity, are shot through with this ghastly banking dreck.

Finance-specific boilerplate

Here are some common standard clauses which, it is submitted, do not belong outside a finance contract. This is an organic list that will grow as I get round to expressing my angst and frustration at crappy legal eagles who keep insisting on this sort of thing:

| Clause | What is does | Why you don’t need it |

|---|---|---|

| Events of Default | A laundry list of events of default, mostly concerned with the solvency and ability to pay sums of money, entitling the “non-Defaulting party” to take extreme, and pre-identified measures, including terminating the agreement | This is the daddy. The thing is, the ordinary rules relating to recovery of damages upon fundamental breach of contract are, for the most part, fine if you are just performing a service contract. They are in fact rather good: they have been honed and smoothed over the centuries by the fast-flowing babble of common law precedent. Financing contracts, in this river, are queer fish: one must navigate tendentious insolvency rules — especially if you are trading across border — to give effect to vitally important set-off and netting rights which are engineered to deliver a specific financial outcome, and might not work as well, or as quickly, when a counterparty is insolvent. Especially where the sums at stake are colossal, you don’t want to be applying to the local courts to recover a debt claim: you don’t want to be in hock to a bankrupt company at all. It is is providing consulting services you can cut your losses by ditching it and finding another consultant. If it owes you three hundred million dollars, it is not so easy being sanguine. Plus, events of default are designed as “self-help” remedies to allow an innocent party to quickly and unfussily exercise its rights and put itself in the best possible position with the least possible resort to the courts and the legal process. |

| No set-off or counterclaim | A provision stating that “all sums shall be paid in full, free of any restriction, condition, set-off or counter-claim, and without deduction or withholding for or on account of tax except where required by law” | Because in the ordinary world or service contract this goes without saying, and the hassle is manageable even where it doesn’t: this is relevant when you are paying cashflows, manufacturing dividends and so on across borders, or where a certain sum arriving at a certain time in a certain place without counterparty nibblement is important. If your client deducts tax from your consulting fees, or has set them off against something you owe it, that’s a bummer for sure, but you’ll survive: it won’t set an ending chain of operational payments into a vortex of destruction. As our friends in the stupid banker cases show us, you don’t have to get things that badly wrong for things to go really, apocalyptically badly wrong. |

| No waiver | Tedious verbiage to the effect that “No failure or delay in exercising, any remedy under this Agreement will operate as a waiver, nor will any single or partial exercise of any right or remedy preclude any other or further exercise thereof or the exercise of any other right or remedy.” | Again, this is all about does this dude owe me the ten million dollars or not rather than “will I get paid my $25,000 consulting fee”. If, out of the goodness of your heart and a realistic view of your long term revenue prospects, you let a distressed creditor off strict enforcement during a tough patch, to help it through a difficult cashflow situation, you don’t want to find you have waved away your rights to get that money later, or not grant that indulgence should it find itself “inexplicably” in the same situation again next time a margin payment is due. |

| No Assignment | Words to the effect that one party can’t assign or transfer its rights without the other’s consent. | The old chestnut from laws 201, is that you cannot unilaterally transfer obligations under a contract in any case; only rights. Transferring rights and obligations is a novation. Everyone has to agree to that. Transfer of rights only — “assignment” — is mostly harmless in any contract, even a finance contract, though that doesn’t stop banking legal eagles getting agitated about it — possibly out of a misfounded suspicion it might upset close-out netting arrangements. (In our rambunctious opinion, it does not and cannot: nemo dat quod non habet.) In any case, nervousness about precisely whom you can invite to enjoy the benefits or suffer the burdens of your contract on your behalf is a quite a bit more of a “thing” in a lending situation, where the action itself — paying or receiving money — isn’t one that requires any skill, competence or personality in itself. (Sorry, banker friends, but it is true).

Now, quite unlike the performance of personal services, simply discharging a payment obligation is, of itself, a non-personal thing: I don’t care who pays the million quid you owe me as long as someone does. But if I have invited Pink Floyd to play at my son’s Barmitzvah I will care, a lot, if they send some other jokers along instead. The thing about money payments isn’t who pays the money, but whether they pay it. But who actually pays the money — as often as not it will be a direct wire from your bank on your behalf, after all — is a very different thing from who is obliged to pay it, and, especially six months out from a coupon payment in a choppy credit environment, this is a personal thing, so boilerplatey legal eagles like to make that clear. With personal services it goes without saying. It is not possible for someone who is not Pink Floyd to perform the obligation of being Pink Floyd.[1] |

| Severability | Claiming the illegality, invalidity or unenforceability of any provision of this Agreement does not affect the rest of its enforceability. | While a severability clause seems counterproductive in most arms’ length, symmetrical commercial settings, there is one where it is not: an asymmetrical commercial setting. A loan. Here, day one the lender ponies up a lot of money, and has his posterior in the proverbial sling until the last day, when the borrower gives the money back. If the contract becomes tangentially illegal in the meantime, then cancelling it would be a really bad outcome for the bank.

Let’s say the bank lends you a hundred million dollars for a year. The terms of the loan are that you must repay in a year, together with fixed interest in the meantime and, on the scheduled repayment date the bank must deliver you a single bowl of M&Ms with the brown ones removed. As a gesture of fun and goodwill, and to reflect what a hip outfit the bank is. You could imagine Northern Rock doing this sort of thing. Everyone happy, right? Now: what should happen if, unexpectedly, a new government is enacted on a platform of irrational hostility to eighties metal bands, and they legislate for it to be illegal — punishable by imprisonment — to doctor M&Ms? Without a functioning severability clause, the contract might be void. Absurd, you might say: this is obviously a meaningless formality. The parties would at once get together and agree to waive the need for the M&Ms. Plainly, no-one is materially affected. But here is the thing. Imagine the borrower is a hedge fund. One of the especially venal, rapacious, locusty ones. It has just had a free option drop into its lap in the shape of a compelling legal reason it might not have to give back a hundred million dollars. God forbid it might opportunistically claim ~ to its horreur, naturally ~ that this contract cannot now be honoured, on pain of imprisonment. It will wheel out its compliance officer, who will mutter about formal compliance with rules and the firm’s duty to its shareholders. Or its investors. It will not be hard for it to contrive reasons that, even though it would love to give the money back, it just can’t. Those who don’t believe this are cordially invited to consider the stupid banker cases: that is exactly what the hedgefunds did to Citi on the Revlon loan debacle. |

| Counterparts | Allows the contract to be signed on different bits of paper | No contract needs a counterparts clause. Not even a finance contract.Black’s Law Dictionary has the following to say on counterparts:

Sometimes it is important that more than one copy of a document is recognised as an “original” — for tax purposes, for example, or where “the agreement” must be formally lodged with a land registry. But these cases, involving the conveyance of real estate, are rare — non-existent, indeed, when the field you are ploughing overflows with flowering ISDA Master Agreements, confidentiality agreements and so on. If yours does — and if you are still reading, I can only assume it does, or you are otherwise at some kind of low psychological ebb — a “counterparts” clause is as useful to you as a chocolate tea-pot. Indeed: even for land lawyers, all it does is sort out which, of a scrum of identical documents signed by different people, is the “original”. This is doubtless important if you are registering leases in land registries, or whatever other grim minutiae land lawyers care about — we banking lawyers have our own grim minutiae to obsess about, so you should forgive us for not giving a tinker’s cuss about yours, die Landadler. [2] ANYWAY — if your area of legal speciality doesn’t care which of your contracts is the “original” — and seeing as, Q.E.D., they’re identical, why should it? — a counterparts clause is a waste of trees. If the law decrees everyone has to sign the same physical bit of paper (and no legal proposition to our knowledge does, but let’s just say), a clause on that bit of paper saying that they don’t have to, is hardly going to help. Mark it, nuncle: there is a chicken-and-egg problem here; a temporal paradox — and you know how the JC loves those. For if your contract could only be executed on several pieces of paper if the parties agreed that, then wouldn’t you need them all to sign an agreement, saying just that, on the same piece of paper? And since, to get that agreement, they will have to sign the same piece of paper, why don’t you just have done with it and have them all sign the same copy of the blessèd contract, while you are at it? But was there ever a logical cul-de-sac so neat, so compelling, that it stopped a legal eagle insisting on stating it anyway, on pain of cratering the trade? There are little eaglets to feed, my friends. |

| No oral modification | Prevents one of your salesguys from modifying the agreement by casual, drunken conversation in a bar | “No oral modification” is a self-contradictory stricture on an amendment agreement, until 2018 understood by all to be silly fluff put in a contract to appease the lawyers and guarantee them an annuity of tedious work. But as of 2018 it is no longer, as it ought to be, a vacuous piece of legal flannel — thanks to what we impolitely consider to be an equally vacuous piece of legal reasoning by no less an eminence than Lord Sumption of the Supreme Court in Rock Advertising Limited v MWB Business Exchange Centres Limited if one says one cannot amend a contract except in writing then one will be held to that — even if on the clear evidence the parties to the contract later agreed otherwise.

This is rather like sober me being obliged to act on promises that drunk me made to a handsome rechtsanwältin during a argument about theoretical physics in a nasty bar in Hammersmith after the end-of-year do, which that elegant German attorney can not even remember me making, let alone wishing to see performed.[3] Hold my beer. |

See also

References

- ↑ Though try telling Roger Waters that since 1981).

- ↑ The JC has great friends in the land law game, back home in New Zealand, and he doesn’t want to upset them — not that they are the easily upset types.

- ↑ I know this sounds oddly, verisimilitudinally specific, but it actually isn’t. I really did just make it up.