Money

“I don’t need money. I need questions answered. Question number one: Can I have some money?”

- —Ford Fairlane, in The Adventures of Ford Fairlane, Rock ’n’ Roll Detective

Money

/ˈmʌni/ (n.)

- The simplest, most elemental, most basic and yet most perplexing thing in all of financial services. In being an abstract, immaterial, token of value, it is a simple, but gravely misunderstood thing. This makes money at its deepest essence, cunisian.

- A will ’o’ the wisp, a woodland sprite, an ephemerality which floats freely of the mortal chains of commerce. It is derivative of nothing, beyond the common opinion of merchants in the town square. It is like Sandy Denny, or one of those free-spirited hippie types that dances round toadstools. It cannot be owned, only held[1] — which is another way of saying whoever holds it holds it, outright, against all the world. No-one has a better claim over a unit of money that the one who, for the time being holds it.

- What it is not: Money is not an asset. It is not property.

Cash demands your total commitment, or nothing. You can’t futz around with it, you can’t declare a trust over it,[2] pledge it, or even hold it for anyone other than yourself. If you could, this would undermine the practical value of money as money: a £5 note, to be meaningful, must be a token worth exactly £5. A bank note has no intrinsic value — it’s a scruffy bit of paper. If its nominal value is £5 but you fear that the person giving it to you may not own it — that is, may not have the unalienable legal right to give that piece of paper to you; that there is a risk that some random may snatch it from your hands after you have given up your own precious goods in exchange for it, alleging some prior, superior, ownership right — then it does not have a value of £5 any more.

It is really important to the economy that banknotes have the value they say they do. So, cash is a special thing. It has special metaphysical properties — or more to the point, it lacks certain metaphysical properties possessed by ordinary chattels.

Holding cash is different from putting it in a bank account

It follows from the above that if you put your money in your bank account, it isn’t your money any more. It is the bank’s.

Wait, wha — ?

Stop. Go see the article.

Whoever holds it holds it outright. No exceptions.

Transfer of cash to another person[3] with the expectation of its return fundamentally, necessarily, creates indebtedness. By transferring cash to someone else in expectation of its return, you convert your own holding of that abstract token into a claim on the estate of the person to whom you transferred it for repayment of that debt. Indebtedness is not in any sense a proprietary claim over some money. It is a simple contractual obligation, owed by the debtor, to pay the creditor an equivalent amount of money. But it confers no rights over that money. There can be no kind of bailment or custody arrangement over money.

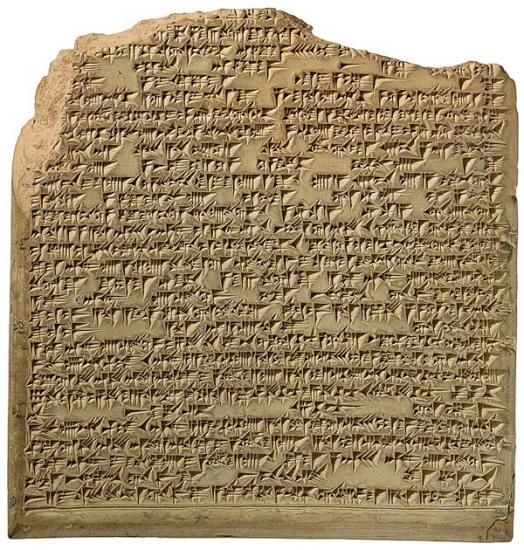

This isn’t just an English law point. It is not a function of the CASS rules. It is fundamental to the nature of cash in any place, under any law. It dates back to the Code of Hammurabi.

An instrument whose deposit doesn’t automatically create indebtedness is not money.

Therefore, you cannot eliminate credit exposure to a person who holds “your” money. If someone else holds it, it isn’t your money. That person owes you an equivalent sum. Event if she has physically and permanently put it aside – that is, she has taken an equal amount of cash out of circulation and put in a vault or something – and the debt represented by that cash payment benefits from some kind of statutory protection against claims from other creditors there is still some basic credit risk. Even this only amounts to a statutory preference as against the holder which defeats claims of lower-ranking creditors.

But what about client money?

We have much to say about client money elsewhere. But the beneficiary of client money protection has no credit risk to the person offering client money protection because that person never holds the cash in question. It is instead placed on deposit with a third party bank. The client does have full credit risk to that third party bank. This tends to surprise those clients who have the dim impression that client money protection is some kind of amulet; a patronus charm; a magical cloak of mithril, protecting the little pot of money in the bank’s vault with their names on it against all machinations of the succubi and incubi who infest their dreams.

Why no, good sir: client money merely changes the banshee to whose freakish conspiracies your little pot of money is exposed, ideally just to a less nasty,[4] more banky type of hobgoblin or foul fiend.

See also

References

- ↑

Girl Guides: Ford! Ford! We just needed to be held!

Ford Fairlane Rock ’n’ Roll Detective: Well, you got the bonus plan. Ohhhhhhhh.

- ↑ You can declare a trust over an account that holds cash, of course: a subtly, but significantly, different thing.

- ↑ This is called “payment”, not “delivery”, as those who have had to dally with physical and cash settlement wording will, to their chagrin, know.

- ↑ I.e., better capitalised and prudentially regulated, but don’t tell the Extinction Rebellion that: nastiness is in the eye of the beholder of course.