OneNDA: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

“{{Maxim|The quotidian is a utility, not an asset}}.”}} | “{{Maxim|The quotidian is a utility, not an asset}}.”}} | ||

[[Boilerplate]]. No legal form has more than an [[NDA]]. To read one is to behold pure, abstracted, ''essence'' of boilerplate. | [[Boilerplate]]. No legal form has more of it than an [[NDA]]. To read one is to behold pure, abstracted, ''essence'' of [[boilerplate]]. In an NDA, ''[[boilerplate]] is all you get''. | ||

Yet generations of [[legal eagle]]s, back to the time of the [[First Men]] — lo, even unto the very [[Children of the Forest]] — have dug themselves into slit trenches to argue the toss over this quotidian contract. It has been some kind of insane compulsion: not one of them ''enjoyed'' it; not one of them saw any ''point'' in it; they found themselves ''compelled'' to do it; drawn to it, like moths to a gaslight; lemmings to a chalky cliff. | |||

“I must negotiate this [[NDA]], because ''this is what I do''. [[It is in my nature]].” | “I must negotiate this [[NDA]], because ''this is what I do''. [[It is in my nature]].” | ||

| Line 19: | Line 21: | ||

===Later ... === | ===Later ... === | ||

The fellowship managed to resist the human impulses to which we agents of the [[Tragedy of the commons|tragic commons]] resort by irrepressible force of habit: the bickering, the [[special pleading]], [[committee]] drafting, pursuit by ring-fixated goblins muttering [[Culpa in contrahendo|baffling ancient curses]]: the cannons to the right of them, cannons to the left: half a league onward rode the OneNDA [[Steering committee]], and generated a nice, simple, pleasant first edition. | |||

Not [[Perfection is the enemy of good enough|''perfect'' — is anything? — but absolutely good enough]]. | |||

It’s too early to stand on the poop-deck with a mission accomplished banner, but OneNDA is getting there. We remain hopeful and optimistic. So, in a gentle further shove, here some observations about what it could all mean. | |||

====Simplification beats technology — and ''helps'' it.==== | |||

''If you simplify, you may not need technology''. There is no need for automation, document assembly, even a mail merge is probably over-engineering. This is to observe that the conundrum facing modern legal eagles is not one of ''[[service delivery]]'', but ''[[Legal service|service]]'' in the first place. Fix the ''content'', and the delivery challenges fix themselves. | |||

''If you simplify, it is easier to apply technology''. To design for technology, design for ''no'' technology. The fewer options, subroutines, [[Caveat|caveats]] and [[conditions precedent]] in your legal forms, the easier they will be to automate. You will get all kinds of second order benefits too: fewer complaints, fewer comments, less time auditing your monstrous catalogue of templates. | |||

The [[JC]]’s [[maxim|handy aphorism]] applies here: {{maxim|first, cut out the pies}}. | |||

====It’s not the [[form]], or even the content, but '''''consensus''''' that matters==== | |||

Once upon a time — until 2021 —if you devised your own short-form NDA, however elegant, you could expect it to be ''rejected''<ref>There ''is'' a “battle of the forms”, even if not apparent to the [[doyen of drafting]].</ref> or [[Mark-up|marked up]] to ''oblivion'' by the [[rent-seeking]] massive.<ref>The [[JC]] knows this, because he’s tried it. No [[counterparts]] clause! No waiver of jury trials! It was still worth doing, but it didn’t completely solve the problem.</ref> Your voice was but a candle in the storm. | |||

OneNDA | But OneNDA, as a community effort, has the potential to change that: interested people came from far and wide to help; everyone<ref>Everyone except [[Ken Adams|the doyen of drafting]] himself, that is: https://www.adamsdrafting.com/onenda-is-mediocrenda-thoughts-on-a-proposed-standard-nondisclosure-agreement/ </ref> checked their agenda at the door. This was what Wikipedians call a “[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barn_raising barn-raising]”. The community came together for the greater good of all. | ||

Now once a barn is raised and community feels ownership in it, it is the very ''fact'' of the barn, rather than how it was built or what it is made of, that is its value. Community assets accrue to the benefit of everyone. The structure, day one, might not be perfect | Now once a barn is raised and community feels ownership in it, it is the very ''fact'' of the barn, rather than how it was built or what it is made of, that is its value. Community assets accrue to the benefit of everyone. The structure, day one, might not be perfect but nor is there any interest in undermining it, much less setting fire to the roof: ''everyone has a stake in the barn.'' ''Everyone'' has [[skin in the game]]. The more people use it, the stronger it gets, the more the crowd who does use it are incentivised to make sure it stands. | ||

Thus, | The more people use it, the more [[Perfection is the enemy of good enough|“good enough” ''becomes'' “perfection”]]. | ||

Thus, tiresome complaints that, for example, it refers to “information that is in the public domain” and not just “information that is public” — I mean, what a [[Knee-slide and jet wings|zinger]] — fall away because no-one ''cares''. Who would take that point? Why? ''Everyone knows what it means''. If there are ten thousand standard NDAs out there using the expression “public domain”, why would anyone take pedantic argument against the weight, and interests, of community consensus? | |||

Rhetorical question. | |||

Community consensus, like an internet protocol, benefits everyone. | |||

====The hard lines discourage [[rentsmithing]] around the edges==== | ====The hard lines discourage [[rentsmithing]] around the edges==== | ||

Once that common standard exists, with the hard lines OneNDA has drawn around itself, there is a further | Once that common standard exists, with the hard lines OneNDA has drawn around itself, there is a further advantage: it dampens [[rentsmithing|peripheral legal-eaglery]] around edge cases, because ''it isn’t worth it'' to argue them. Not even for a [[pedantry|pedant]]. | ||

We all know the common fripperies thrown into an NDA negotiation by way of a dominance display: [[indemnities]]; [[Exclusive licence|exclusivities]]; [[non-solicitation]] and so on. These will quickly be rejected out of hand: the courtship ritual of inserting then removing them is not costless. It is [[tedious]], distracting, and it takes time. | |||

By drawing hard lines around itself, OneNDA makes itself unavailable as a host to that kind of pointless rutting. And it is hard to [[rentsmith]] without a “host” contract. To do it, the [[Rentsmith|rentsmithor]] must find a new host agreement, or make a new one, for this plainly cosmetic purpose. It will be discouraged from doing that for fear of looking stupid. | |||

''A standardised form discourages peripheral negotiation''. | |||

==== | ====Shifting the knee of the curve==== | ||

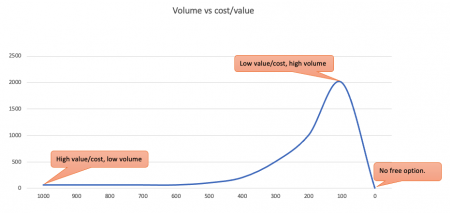

[[File:Contract volume curve.png|450px|thumb|right|The more a contract costs to negotiate, the fewer of them you can do. There’s no free option if everything is negotatiated.]] | [[File:Contract volume curve.png|450px|thumb|right|The more a contract costs to negotiate, the fewer of them you can do. There’s no free option if everything is negotatiated.]] | ||

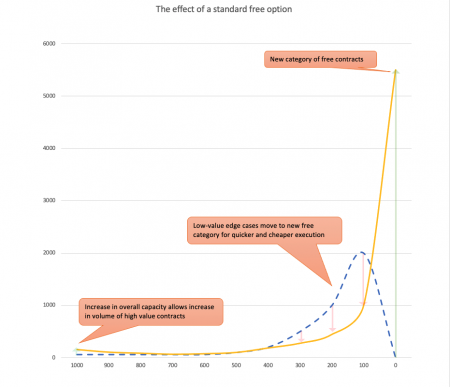

[[File:Contract curve shifted.png|450px|thumb|right|Adding a free, no-negotiation option creates a range of customers you couldn't afford to onboard, but incentivises marginal cases to take the free option too]] | [[File:Contract curve shifted.png|450px|thumb|right|Adding a free, no-negotiation option creates a range of customers you couldn't afford to onboard, but incentivises marginal cases to take the free option too]] | ||

Creating a simple and standard alternative | Creating a simple and standard alternative affects the “legal complexity curve’.<ref>This is a concept I basically made up on the hoof. Go with me on this one.</ref> It pulls it ''down'' and to the ''right'', being the directions you want it going in. | ||

Let us tell you a story, through the prism of some fancy charts. They are stimulations of a real-life case. | |||

The problem: a broken contracting process: too slow, too costly, too many errors. The “complexity distribution’ was just as you would expect: lots of low-value contracts, a few high-value ones. The errors were spread evenly throughout: most, therefore, in the low value contracts. | |||

The idea: reduce the negotiation workload and somehow give the team more time to focus on the higher value contracts. | |||

The approach: standardise just the lowest value contract. It was easiest to fix, most boring, and had the highest volume. Leave the rest be. | |||

Outcome: Overnight, half the contract volume was automated. | |||

But ''then'': | |||

*Volumes in the automated contract ''doubled overnight'': | *Volumes in the automated contract ''doubled overnight'': as it was faster easier and error-free, the marginal cost plummeted, so the volumes spiked. | ||

*Some “marginal” customers in | *Some “marginal” customers in adjacent categories chose to move to the free contract: they were happy to trade speed and cost for customisation. It’s a simple trade: sign this and trade now, or tie your legal team up for three weeks. Thus the “knee” of the curve deepened and shifted to the right. | ||

* | *Volumes of the ''highest'' value categories went up, as the team had more bandwidth, processed the contracts more quickly and with fewer errors. | ||

*As a result, total output of the team ''doubled''. | *As a result, total output of the team ''doubled''. | ||

The one thing that did ''not'' happen was the forced [[redundancy]] of the team. They were busier than ever, only on more challenging stuff. | The one thing that did ''not'' happen was the forced [[redundancy]] of the team. They were busier than ever, only on more challenging stuff. | ||

Revision as of 19:23, 26 August 2021

|

The design of organisations and products

|

SYNOPSIS: Some cheeky little hobbits form a fellowship and set out on a perilous adventure to confront the fearsome Smarkup, a wingèd dragon made out of boilerplate that jealously guards the huge pile of rent it has appropriated from nearby merchants.

First act goes well.

In Bozo Baggins’ burrow, there was a sign above his desk, carefully hand-painted by his uncle Dildo:

Boilerplate. No legal form has more of it than an NDA. To read one is to behold pure, abstracted, essence of boilerplate. In an NDA, boilerplate is all you get.

Yet generations of legal eagles, back to the time of the First Men — lo, even unto the very Children of the Forest — have dug themselves into slit trenches to argue the toss over this quotidian contract. It has been some kind of insane compulsion: not one of them enjoyed it; not one of them saw any point in it; they found themselves compelled to do it; drawn to it, like moths to a gaslight; lemmings to a chalky cliff.

“I must negotiate this NDA, because this is what I do. It is in my nature.”

Kudos, therefore, to the team at TLB for doing something about it.[1]

The JC put his sclerotic old shoulder to the wheel, for whatever that was worth, and commended his friends, relations and readers to do the same; especially those who occupy places in the firmament, or up the fundament, higher than his own.

Start with the NDA, who knows where it may lead?

Later ...

The fellowship managed to resist the human impulses to which we agents of the tragic commons resort by irrepressible force of habit: the bickering, the special pleading, committee drafting, pursuit by ring-fixated goblins muttering baffling ancient curses: the cannons to the right of them, cannons to the left: half a league onward rode the OneNDA Steering committee, and generated a nice, simple, pleasant first edition.

Not perfect — is anything? — but absolutely good enough.

It’s too early to stand on the poop-deck with a mission accomplished banner, but OneNDA is getting there. We remain hopeful and optimistic. So, in a gentle further shove, here some observations about what it could all mean.

Simplification beats technology — and helps it.

If you simplify, you may not need technology. There is no need for automation, document assembly, even a mail merge is probably over-engineering. This is to observe that the conundrum facing modern legal eagles is not one of service delivery, but service in the first place. Fix the content, and the delivery challenges fix themselves.

If you simplify, it is easier to apply technology. To design for technology, design for no technology. The fewer options, subroutines, caveats and conditions precedent in your legal forms, the easier they will be to automate. You will get all kinds of second order benefits too: fewer complaints, fewer comments, less time auditing your monstrous catalogue of templates.

The JC’s handy aphorism applies here: first, cut out the pies.

It’s not the form, or even the content, but consensus that matters

Once upon a time — until 2021 —if you devised your own short-form NDA, however elegant, you could expect it to be rejected[2] or marked up to oblivion by the rent-seeking massive.[3] Your voice was but a candle in the storm.

But OneNDA, as a community effort, has the potential to change that: interested people came from far and wide to help; everyone[4] checked their agenda at the door. This was what Wikipedians call a “barn-raising”. The community came together for the greater good of all.

Now once a barn is raised and community feels ownership in it, it is the very fact of the barn, rather than how it was built or what it is made of, that is its value. Community assets accrue to the benefit of everyone. The structure, day one, might not be perfect but nor is there any interest in undermining it, much less setting fire to the roof: everyone has a stake in the barn. Everyone has skin in the game. The more people use it, the stronger it gets, the more the crowd who does use it are incentivised to make sure it stands.

The more people use it, the more “good enough” becomes “perfection”.

Thus, tiresome complaints that, for example, it refers to “information that is in the public domain” and not just “information that is public” — I mean, what a zinger — fall away because no-one cares. Who would take that point? Why? Everyone knows what it means. If there are ten thousand standard NDAs out there using the expression “public domain”, why would anyone take pedantic argument against the weight, and interests, of community consensus?

Rhetorical question.

Community consensus, like an internet protocol, benefits everyone.

The hard lines discourage rentsmithing around the edges

Once that common standard exists, with the hard lines OneNDA has drawn around itself, there is a further advantage: it dampens peripheral legal-eaglery around edge cases, because it isn’t worth it to argue them. Not even for a pedant.

We all know the common fripperies thrown into an NDA negotiation by way of a dominance display: indemnities; exclusivities; non-solicitation and so on. These will quickly be rejected out of hand: the courtship ritual of inserting then removing them is not costless. It is tedious, distracting, and it takes time.

By drawing hard lines around itself, OneNDA makes itself unavailable as a host to that kind of pointless rutting. And it is hard to rentsmith without a “host” contract. To do it, the rentsmithor must find a new host agreement, or make a new one, for this plainly cosmetic purpose. It will be discouraged from doing that for fear of looking stupid.

A standardised form discourages peripheral negotiation.

Shifting the knee of the curve

Creating a simple and standard alternative affects the “legal complexity curve’.[5] It pulls it down and to the right, being the directions you want it going in.

Let us tell you a story, through the prism of some fancy charts. They are stimulations of a real-life case.

The problem: a broken contracting process: too slow, too costly, too many errors. The “complexity distribution’ was just as you would expect: lots of low-value contracts, a few high-value ones. The errors were spread evenly throughout: most, therefore, in the low value contracts.

The idea: reduce the negotiation workload and somehow give the team more time to focus on the higher value contracts.

The approach: standardise just the lowest value contract. It was easiest to fix, most boring, and had the highest volume. Leave the rest be.

Outcome: Overnight, half the contract volume was automated.

But then:

- Volumes in the automated contract doubled overnight: as it was faster easier and error-free, the marginal cost plummeted, so the volumes spiked.

- Some “marginal” customers in adjacent categories chose to move to the free contract: they were happy to trade speed and cost for customisation. It’s a simple trade: sign this and trade now, or tie your legal team up for three weeks. Thus the “knee” of the curve deepened and shifted to the right.

- Volumes of the highest value categories went up, as the team had more bandwidth, processed the contracts more quickly and with fewer errors.

- As a result, total output of the team doubled.

The one thing that did not happen was the forced redundancy of the team. They were busier than ever, only on more challenging stuff.

See also

- Confidentiality agreement

- Perfection is the enemy of good enough

- The quotidian is a utility, not an asset

References

- ↑ Don’t just read about it here: go see: https://www.onenda.org

- ↑ There is a “battle of the forms”, even if not apparent to the doyen of drafting.

- ↑ The JC knows this, because he’s tried it. No counterparts clause! No waiver of jury trials! It was still worth doing, but it didn’t completely solve the problem.

- ↑ Everyone except the doyen of drafting himself, that is: https://www.adamsdrafting.com/onenda-is-mediocrenda-thoughts-on-a-proposed-standard-nondisclosure-agreement/

- ↑ This is a concept I basically made up on the hoof. Go with me on this one.