Pronoun: Difference between revisions

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Amwelladmin (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

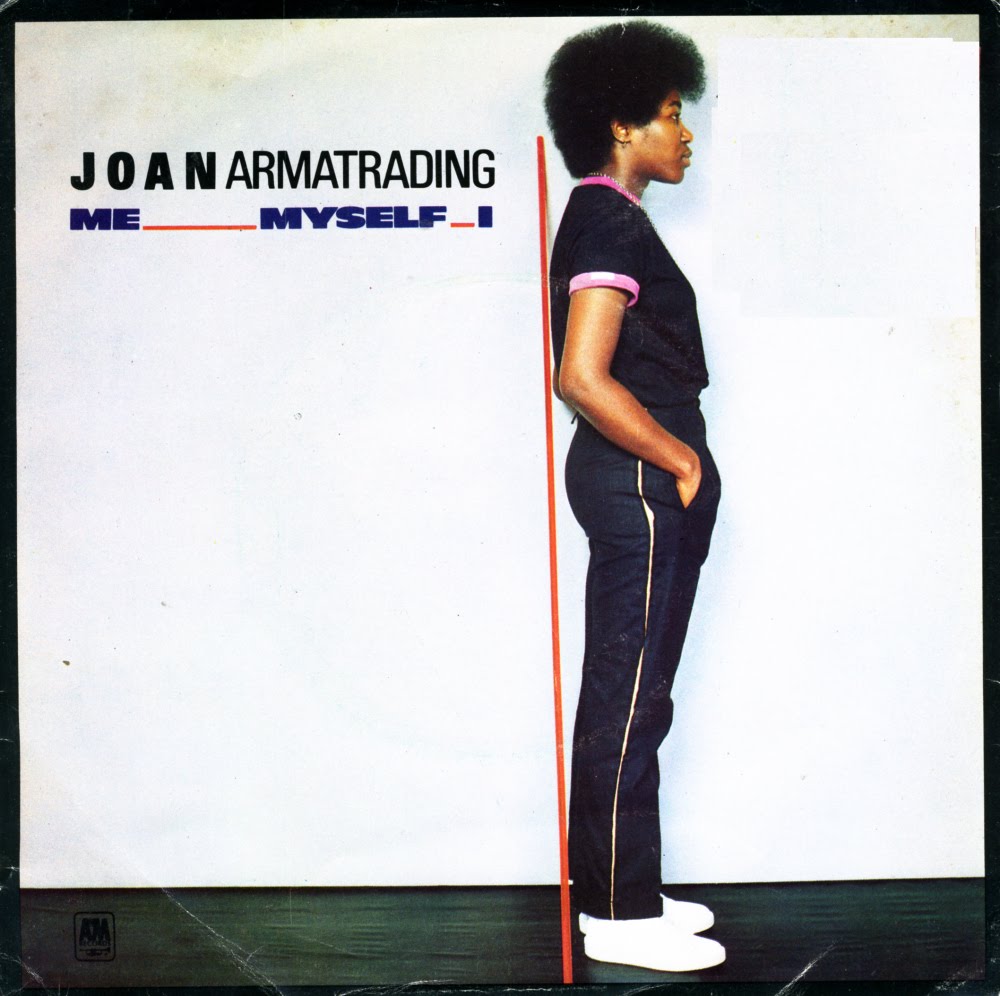

{{ | {{a|drafting|{{image|Me myself I|jpg|Would the superb Ms. A.’s [[LinkedIn]] profile say “Joan Armatrading (Me/Myself/I)”? Trick question: Joan Armatrading wouldn’t ''have'' a [[LinkedIn]] profile.}}}}[[Legal eagle]]s distrust [[pronoun]]s because they (pronouns, that is, not [[legal eagle]]s) tend to be short and idiomatic. | ||

Even [[legal eagle]]s of great experience, wisdom and status struggle: witness [[Lord Justice Waller]]’s travails in {{casenote|Lloyds Bank|Independent Insurance}}. | |||

Using them, they feel, infinitesimally lowers a bar that was put up for a reason: ''to keep [[muggle]]s out''. It is a small thing: abstention from pronouns doesn’t change the semantic content, much less its legal freighting, but it makes text just that little bit denser to those who do not have a direct financial incentive in reading it. | |||

The official excuse has something to do with imprecision: “you” and “it” | The official excuse has something to do with imprecision: “you” and “it” may be the {{tag|subject}} ''or'' {{tag|object}} of a sentence: unlike those ultra-precise Germans, we Englanders only half-heartedly [[declension|decline]] our [[pronoun]]s. | ||

“[[We]],” in one of those ghastly interpersonal contracts that are set up like a conversation between friends and not the stiff passive account of a scientific experiment they should be, is [[definition|defined]] as the ''drafter'' of the contract (as opposed to “[[you]],” its recipient, but in idiomatic English, can refer to both of them together. How are we meant to know? | |||

But the English language, shot through as it may be with these and other ambiguities, has yet managed to hang on in the evolutionary arms race of linguistic models. It has done rather well, in fact, all things considered. ''Too'' well, some might say. | |||

There is | There is an argument that [[Doubt|constructive ambiguity]] is no bad thing. Perhaps a “runniness at the edges” of one’s contractual commitments and rights might moderate one’s tendency to officiousness when policing one’s [[relationship agreement|commercial relationship]]s. Any that can encourage merchants away from the docs and towards ''calling'' the other guy has got to be a good thing. | ||

{{pronouns and gender}} | |||

{{sa}} | {{sa}} | ||

*[[ | *[[Sexist language]] | ||

{{Ref}} | {{Ref}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:44, 24 November 2022

|

The JC’s guide to writing nice.™

|

Legal eagles distrust pronouns because they (pronouns, that is, not legal eagles) tend to be short and idiomatic.

Even legal eagles of great experience, wisdom and status struggle: witness Lord Justice Waller’s travails in Lloyds Bank v Independent Insurance.

Using them, they feel, infinitesimally lowers a bar that was put up for a reason: to keep muggles out. It is a small thing: abstention from pronouns doesn’t change the semantic content, much less its legal freighting, but it makes text just that little bit denser to those who do not have a direct financial incentive in reading it.

The official excuse has something to do with imprecision: “you” and “it” may be the subject or object of a sentence: unlike those ultra-precise Germans, we Englanders only half-heartedly decline our pronouns.

“We,” in one of those ghastly interpersonal contracts that are set up like a conversation between friends and not the stiff passive account of a scientific experiment they should be, is defined as the drafter of the contract (as opposed to “you,” its recipient, but in idiomatic English, can refer to both of them together. How are we meant to know?

But the English language, shot through as it may be with these and other ambiguities, has yet managed to hang on in the evolutionary arms race of linguistic models. It has done rather well, in fact, all things considered. Too well, some might say.

There is an argument that constructive ambiguity is no bad thing. Perhaps a “runniness at the edges” of one’s contractual commitments and rights might moderate one’s tendency to officiousness when policing one’s commercial relationships. Any that can encourage merchants away from the docs and towards calling the other guy has got to be a good thing.

Pronouns and gender

- Fools rush in where libtards fear to tread.

- — Alexander Pope

Much ink and no small amount of bile has been spilt on the question of gender inclusivity in language. Some of it, we cautiously venture, speaks to a bit of softness in the command of grammar from those who study grievances.

There is a fashion towards signposting one’s preferred personal pronoun wherever the opportunity arises: business cards, email signoffs, LinkedIn profiles and so on. So, “Otto Büchstein (They/Them)”, for example.

Now the JC has no quarrel with how any of his fellow humans want to identify their own gender — variety being the spice of life, the more concoctions we have between us the better — though one does risk tripping over the conclusion that lies down that road, if you go far enough along it, that there should be no genders; we are all different, all individuals and the very idea of coming down from the trees and starting to decline nouns in the first place was a ghastly mistake.[1] But with even that aside, there are still a few puzzling aspects about this behaviour.

Firstly there is that slash; that virgule. As with “and/or”, “(she/her)” is an ungainly construction, and it speaks to a certain fussiness unrelated to one’s wish to be clear about one’s gender. Why include nominative and accusative? Are there some for whom gender differs depending on their position in a sentence? Can one be a he when a doer, and a she when a done to? If the goal is to neuter the power structures implicit in our language, this seems an odd way of going about it. And if that is the idea, why stop at subject and object? What about the possessive? Shouldn’t it be “(she/her/hers)”? And, actually, why not include datives, genitives and ablatives? Will we eventually go the whole hog and append “(she/her/her/her/her/hers)”?

Second, for the great majority of the population — the whole “cis-normal” part, at least — there’s already a way of unfussily designating your gender: your title: Mr., Mrs., Ms., Miss, and Master. Of this great mass of hetero-normativity, only academics and medics have a quandary. Even they could fix it, if they cared to, by adding a gendered title to to their honorific, the same way judges do: Mr. Doctor Jung; Mrs. Doctor Freud, and so forth.

Third, this pronoun angst is directed only at third-person singular pronouns. The other five buckets are fine as they are. Yet, when we address someone directly, we don’t use the third person, except to distance ourselves from our own tendentious but firmly-held opinions, as the JC often does. [2]

The second person pronoun, — “you” for most of the English speaking world, “y’all” for the Americans, “youse” for the kiwis — is perfectly gender-inclusive already.[3] This is the one we use invariably for interpersonal communication: wherever you may be on the gender spectrum, you remain politely, unoppressively, uncontroversially, incontrovertibly, you. We venture that language evolved this way precisely because of the difficulties one would otherwise have making polite conversation with unfamiliar individuals of an apparent, but not definite, feminine or masculine bearing.

So, the “(he/him)” designation appears to stipulate how one should “gender” a person when communicating about that person with someone else. I am going to get in trouble for saying this, readers, but that strikes me as bossy. Who are you to tell me how to moderate the language I use with someone else? Not to say, a little delusional: aren’t my choices of the pronoun I use when talking about you the least of your concerns? Shouldn’t you be more concerned about nouns and adjectives? (What if I call you “bossy”? Or a “pronoun bore”?)

The JC dreads to think what people say about (he/him/his) behind (he/his/his) back: if the worst they do is to misgender (he/him/his) then all is well in the world, frankly.

See also

References

- ↑ The problem with atomising identity groups, to avoid those at the margins being categorised in a way that doesn’t suit them, is that “margins” are a property of any group, however small, until it numbers one. Thus, any philosophy that emphasises marginalised identities will tend to fray at the edges.

- ↑ Though this is to switch first for third person, not the second. One hardly needs to lecture the world on how one should gender oneself.

- ↑ Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby made this point well in her show Douglas.