Legal mark-up

|

Negotiation Anatomy™

|

A lawyer’s stock-in-trade, her currency, the oxygen that gives her daily routine meaning and her role physical substance. For what is she if not her comments?

Ego sum id quod dico - Si quaeris causidicum loqui, locutus est tibi

If you ask a lawyer for comments, she will give you some, whether your draft needed them or not. This is a founding crux of the anal paradox. For a mark-up proves your lawyer has read the agreement, considered its content, and justified her fee. It’s in her nature. It is what she does.

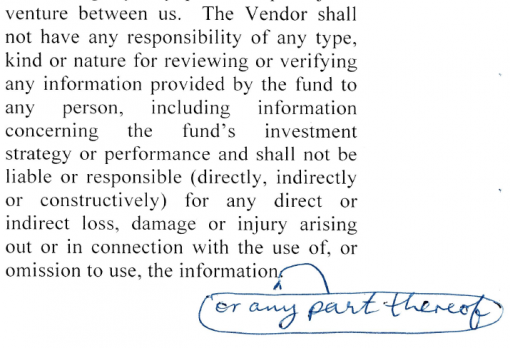

No text is immune from adjustment, and if your only objective is to show you've read it, slipping in a harmless “for the avoidance of doubt”, a “without limitation”, an “as the case may be” or — though on a fraught negotiation this is pushing it, be warned — an “(if any)” is a professionally satisfying but yet non-invasive way of achieving that.

No such ornamentation is calculated to improve the elegance of the text, of course. To do that you will need to disentangle some convoluted grammar — perhaps by deleting an “as the case may be”.[1] This will be seen as enemy action, especially if your edits are not directed at some legal content, however spurious. It is also axiomatic that all legal mark-up must overcome the Biggs threshold.

The Biggs constant

Any Legal markup can be situated somewhere on a “utility continuum”, between the deal-killing blockbuster, whereby a legal eagle saves her client from certain ruin, at one end, and guileless frippery, by dint of which she scrapes over her billable threshold for the month, at the other. The median point is, we need hardly say, nearer the fripperous end, but if you venture a few standard deviations past that, you approach an absolute theoretical minimum, beyond which the utility of any legal mark-up is utterly nil. That final, infinitesimal point, past which the thinnest atomic strand of half-hearted value can be no further reduced — the so-called “Biggs constant” — was first isolated in 1997 when, either by deliberate design or happy accident, a gentleman from the in-house team at a leading financial services institution found it while marking up a pricing supplement he had received by fax. From me. Despite the Byzantine complexity of the document, his only comment was a direction to his diligent counsel — yours truly — to remove the bold formatting from a full stop. This he communicated, also by fax, at 2:35 in the morning. In the kind of irony that accompanies so many of the world’s most momentous occasions, it turned out upon inspection that the full stop wasn’t bold in the first place, but was a printed artefact from the low resolution of the fax.

See also

References

- ↑ be careful not to add the same thing in one place and delete it in another: this will be seen as hostile action.